A Last Letter from Gallipoli

“I build castles in the air every day about our reunion.”

Private Thomas Anderson Whyte, letter to Eileen Wallace Champion, AWM Private Records collection (PR04722).

Circular silver frame with velvet backing, the front face of the frame has a decorative pattern running the entire circumference of frame. Displayed inside the frame is a black and white photo of Thomas Anderson Whyte smoking a pipe, dressed in blazer. A blue velvet bow, acting as a suspender, is sewn to the backing.

In the pre-dawn stillness of 25 April 1915, it is not difficult to imagine 28 year old Private Thomas Anderson Whyte peering into the darkness from his transport ship, straining to catch sight of the peaks of the Gallipoli peninsula visible only as silhouettes in the fading moonlight. We cannot know the many thoughts, reflections and fleeting fears of each soldier that day. But we do know something of what Tom Whyte may have thought. Facing his first glimpse of action in a few hours’ time, foremost in his thoughts was his young fiancée back home and the uncertain future the war had brought upon them.

Since embarking for the war, Tom had shared his impressions and travels with his sweetheart at home through a series of letters. On 24 April 1915, bound for Gallipoli, once again Tom had put pencil to paper; the words he wrote survive 100 years later in the Australian War Memorial’s Private Records collection. Through these letters we learn the story of Tom Whyte and his fiancée, Eileen Wallace Champion – it is also the story of so many young men and women who suffered the loss of life and love during the First World War.

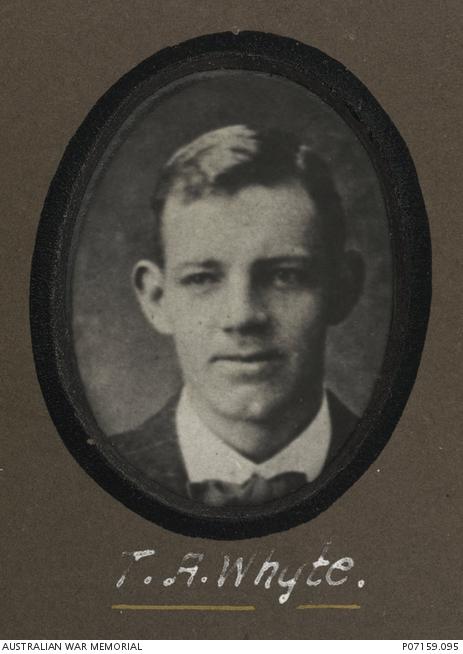

Private Thomas Anderson Whyte responded to the call to duty as soon as he could, enlisting just weeks after the outbreak of war. In October 1914 he embarked from Adelaide with the 10th Infantry Battalion aboard HMAT Ascanius, bound for training in Egypt. He described himself on his Service Record as a 28 year old agent from Hyde Park, a man standing 5 feet 11.5 inches, with fair hair and blue eyes. A circular photo frame suspended on a ribbon in the Memorial’s collection contains a photograph of Tom; dressed in a blazer and smoking a pipe, he was a young man full of character, with prominent ears and an honest face.

Tom had attended St Peters Anglican College in Adelaide and was a very fine athlete in his chosen sports, rowing and lacrosse. Rowing was a great passion for Tom. A popular member of the Mercantile and Adelaide Rowing Clubs, he served on committees and represented South Australia at interstate competitions with great success. His photograph is one of 131 other photographs displayed on the honour board of the Adelaide Rowing Club of those who enlisted for active service in the First World War. Tom was described by a peer as “one of the best oarsmen South Australia ever produced.”[1]. Besides being a champion rower, Tom was also widely regarded in his social circles as “a good sport and kind-hearted man.”[2]

Like many responding to the call, he had left behind a young fiancée, Miss Eileen Wallace Champion. We don’t know how Thomas and Eileen met, but their romance and engagement had been firmly established for two and a half years by the time Tom enlisted in 1914. He corresponded at length with Eileen throughout the voyage to Egypt and his training in Mena Camp. His letters reveal a sensitive, intelligent, curious and courageous young man. Vividly, he describes the exotic and unfamiliar landscapes he experienced; stepping ashore on a misty evening to travel to Mena Camp as part of an advance party, the ancient treasures in the Museum of Antiquities, and the curio shops of Egypt. Intermixed with reports of drill marches and brigade manoeuvres are also thoughts of home and a future of wedded bliss, with plans of homes and glory boxes eagerly discussed. He recorded copies of these letters in a notebook; tucked between the pages was a photograph of Eileen, which Tom would prop up to look upon as he wrote.

Studio portrait of 47 Private Thomas Anderson Whyte, 10th Battalion who was a 28 year old agent from Hyde Park, South Australia when he enlisted on 19 August 1914.

Studio portrait of Eileen Wallace Champion, fiancee of 47 Private (Pte) Thomas Anderson Whyte.

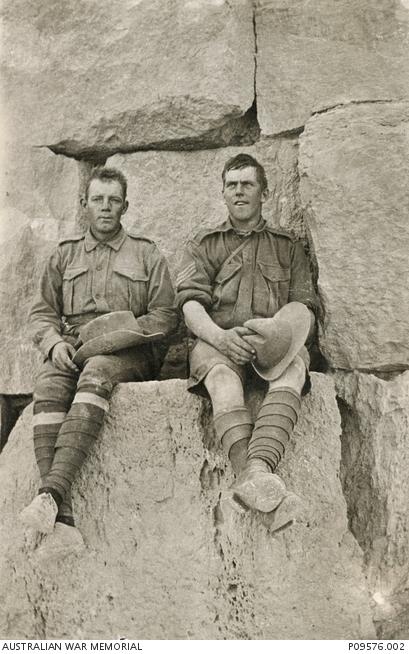

Tom’s letters also feature lively discussion of the school and rowing mates he had embarked with in the 10th Battalion, one of the first infantry units raised for the war. He is pictured with several of his mates from St Peters Anglican College in Adelaide in Egypt in late 1914. Their mateship was strong, and Whyte along with friends Philip de Quetterville Robin, Malcolm St Aiden Teesdale Smith and future VC recipient Arthur Seaforth Blackburn made a pact whilst at Mena Camp to not be separated by way of accepting non-commissioned positions. Sport also figured prominently during these days of training. The 10th Battalion had formed a lacrosse club after hearing about similar battalion teams, and Tom enjoyed the friendly competitiveness of these matches. He captained the 10th Battalion’s lacrosse team, and his team mate (and friend from Adelaide Rowing Club days) Randall Lance Rhodes wrote to the Adelaide Register about some of the hard-fought matches. Defeated 20-6 by an English team, ‘The Terriers’, which by accounts contained several Olympic athletes, Rhodes wrote “…although the scores look bad I don’t think they are a true indication of the game. We had a very enjoyable match…all our crowd are in the best of health.”[3]

Informal group portrait of nine members of the 10th Battalion, all of whom enlisted in 1914, and embarked from Adelaide, SA, on 20 October 1914 aboard HMAT Ascanius and served at Gallipoli. All of these men, except Private (Pte) Guy Fisher and Pte Eric Meldrum were students at St Peters Anglican College in Adelaide, and five of them died during the First World War. Pte Thomas Anderson Whyte is in the front row on the left.

Although accompanied by his mates and keenly following the progress of the war, Tom’s heart was still at home. “I build castles in the air every day about our reunion” he wrote to Eileen on 22 January 1915. In one of the rare fragmentary letters in the collection from Eileen to Tom, amongst cheerful news of home she confesses her fears for him, “Tom dear, it’s so horrible not knowing where you are, or where to send my next letter to you, and I hate thinking you’re nearer the Front…” On 26 February Tom offered comfort to Eileen that he would return safely, “I feel as certain of coming back whole as it is possible to be.”

But Tom Whyte was not naïve about the devastation of war. On 24 April 1915, aboard a transport ship bound for Gallipoli, Tom Whyte once again put pencil to paper. Facing his first glimpse of action in a few hours’ time, he wrote a profoundly raw letter to his fiancée lest he fell in battle the next day. His words reveal the heartfelt fears of a soldier facing an uncertain future.

“My Dear Sweetheart, I thought of writing this in case I went under suddenly. Not that at present I have any thought of not seeing you again but in case of accidents.”

Tom hoped that the letter would never be sent, “May this letter never be necessary. But the thought that hurts worst of all is of you and your sorrow.” But at the moment of writing, Tom found solace in the thought that the future would be a happy one for Eileen. “Just think of me as non-existent in spirit, blotted out completely,” he wrote. “It would soften the last thoughts if I knew you would be really happy again… Goodbye my love, may you get all the happiness you deserve, that will be my last wish.”

Sadly, this was Private Tom Whyte’s last letter. His friend, Arthur Blackburn VC, wrote some months after the Gallipoli landing about Tom’s fate that day in a letter published in the Adelaide Register. On the morning of the Landing, the 10th Battalion had been divided into two parts – the first would row ashore just before dawn in the first wave of soldiers to land, and the second would land just after daybreak. Tom Whyte was in the latter group. Blackburn describes the scene of Tom’s final moments,

“You have no doubt read in the papers an account of our landing, and have seen that after daylight the dangers of landing were increased considerably. The men off the transports had partly to be towed, and partly to be rowed ashore amidst a hail of shrapnel and bullets that was simply indescribable. Now, the most dangerous position of the lot was that of the men who were rowing, as they could take no shelter… Tom immediately grasped the situation, and, as everyone knew he would, volunteered his services as a rower. As the boat crept in towards the shore the fire became hotter and hotter… just as the boat touched the shore Tom slipped over on to the bottom of the boat… he was badly hit…”[4]

Arthur Blackburn

Informal portrait of 47 Private (Pte) Thomas Anderson Whyte (sitting left) and 159 Sergeant John Rutherford Gordon sitting on one of the large stones of the Great Pyramid at Giza.

Tom Whyte, the champion rower, died that evening aboard the Hospital Ship HMAT Gascon before firing a single shot in the war he had travelled so far to join. Blackburn heard of his friend’s death four days later. Tom’s courageous nature was confirmed by reports from the men he had rowed ashore; “no one was more cheerful than he. He was joking and laughing all the way to the shore, and our battalion has lost one of its best soldiers.”[5]

Sitting beside him as he lay dying was Sister Katherine Lawrence Porter, Tom’s last nurse. Sister Porter – ‘Kitty’, as she was known – was also engaged to be married, and felt something of the heartache the death of this young man would cause. She wrote some months later on 26 January 1916 to comfort the devastated Eileen,

“I remember Private Tom Whyte very well. The poor man came on the Gascon during the morning. He had an abdominal wound and was taken to the operation room almost at once and everything possible was done for him… the only thing he was worried over was some package being delivered to his friend… I feel certain that there must have been some message for you in it… it was knowing that he was engaged made me stay on duty a little longer to be what comfort I could to him. It was a terrible day for us all and I saw so much that was awful that day.”[6]

Sister Katherine Lawrence Porter

Sister Porter’s letter had offered something beyond value to Eileen – the knowledge and closure of knowing the fate of her sweetheart on the battlefield. In a chaotic war, many were never to know the last moments of their loved ones. Private Thomas Whyte was buried at sea; his name appears on the Lone Pine Memorial at Gallipoli and on panel 61 on the Roll of Honour.

As you may have guessed, the message Sister Porter had mentioned was Tom’s last letter, which was packed with his sparse belongings (a razor, cigarette case, wristlet, photos, letters and a pen) and sent home to Australia. Cherished by Eileen for a lifetime, it was donated to the Australian War Memorial almost 100 years after it was written, by her children. The collection is a special one. Tom and Eileen’s letters contain the exuberance and future dreams of young lovers eager to live their lives together, the lively curiosity of a brave young man who volunteered under the most dangerous of circumstances to row his mates to shore, and the devastation of a young love broken by war.

The story of Private Thomas Whyte and Eileen Champion is featured in Episode 2: The Landing of the History Channel’s new documentary The Memorial: Beyond the Anzac Legend.

The Memorial is interested in getting in touch with possible relatives of Private Tom Whyte, who had a brother (J.A. or T.A. Whyte) resident in Sydney at the time. Please contact us at Private Records if you have any information.

The Memorial would also be interested in hearing from descendants of Sister Katherine Porter. Sister Porter has her own story. She was 29 when she enlisted on 20 March 1915 and served in Egypt and France with the Australian Army Nursing Service. She had been stationed in the small town of Roye on the Somme in 1918 when it was captured – she narrowly avoided being taken a Prisoner of War. Kitty returned home to Australia in June 1919 and was welcomed home in a celebration in her home town of Milton. Sadly, after providing so much comfort to the wounded and their loved ones at home, Sister Porter also became a casualty of the war. Kitty had cared for the sick and wounded throughout the voyage home, and contracted influenza soon after arriving in Australia. She died on 16 July 1919. Her funeral was attended by full military honours, and Sister Porter received the Royal Red Cross award for her dedicated service. Buried in Waverly General Cemetery in Sydney, her name is on panel 188 of the Roll of Honour.

References

[1] ‘The Late Pte Whyte’, Adelaide Register, 4 May 1915, p6.

[2] Ibid.

[3] ‘Lacrosse in Egypt', Adelaide Register, 22 April 1915.

[4] ‘A Real Hero’, Adelaide Register, 6 August 1915, p9.

[5] Ibid.

[6] AWM Private Records collection PR04722.