A Home on a Southern Hill

A Home on a Southern Hill explores the conception and purposes of the Australian War Memorial and tells the story of the Memorial building from C.E.W. Bean’s initial sketch to inauguration on 11 November 1941.

C.E.W. Bean first conceived the Memorial as he witnessed the horrors of the Western Front in 1916. He envisaged a Memorial that would commemorate through understanding: where Australians who had not served would come to understand the experience and contribution of the Australian Imperial Force through a museum and archive.

The names of those who had died would be included in a Roll of Honour, to create a place where the living would feel the presence of the fallen and the enormity of their individual and collective sacrifice.

However, it would take many years before these ideas were given physical form.

When an architectural competition in 1925 failed to produce a satisfactory design for the building, two of the entrants, Emil Sodersteen and John Crust, were asked to work together. Their joint design, combining Crust’s concept for the Roll of Honour being inscribed within cloisters around a garden courtyard with Sodersteen’s solemn and elegant style, was approved by Parliament in 1928. Despite set-backs and controversies throughout the 1930s, their plan forms the basis of the building that opened in 1941, and which we see today.

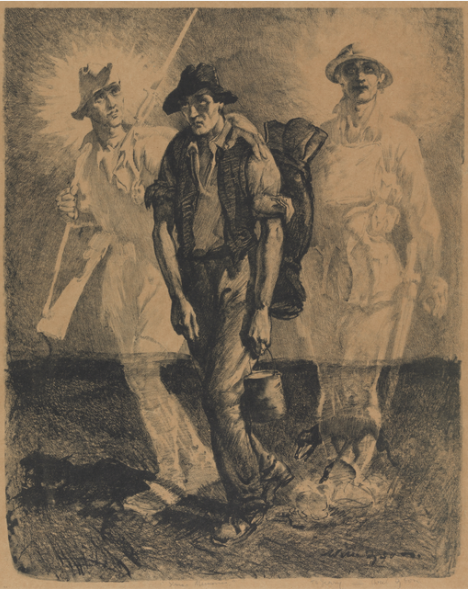

Calling them home

Depicting a ghostly bugler calling the spirits of Australia’s war dead to the yet-to-be-built Australian War Memorial, Will Dyson’s 1928 cartoon Calling them home illustrates the notion that the Memorial was to be for the fallen as well as for the living.

The accompanying poem reads:

They dreamed of leave that never came. Now each dead man is a living fame.

But dreams it still.

They dream of a call to a last route march, back to a land where the grey gums arch.

To a home on a Southern hill.

The cartoon and poem encapsulate the conception and purposes of the Australian War Memorial: as a place for the living – to remember, grieve, and understand – and for the fallen – as a tomb fitting of their sacrifice, and a place for their spirit to reside.

[AWM93.2.5.4.Part6.80]

Xmas memories

Will Dyson joined the AIF as an honorary lieutenant and began creating images of the AIF on the Western Front in December 1916. He was appointed Australia’s first official war artist in May 1917, and came to work closely with Bean and head of the Australian War Records Section and later Memorial Director Captain John Treloar. In this cartoon, Xmas memories (1929), and Calling them home (1928), Dyson depicts a belief that the spirits of the fallen remained present to their friends and loved ones – an idea common among the soldiers of the Western Front.

[ART50203]

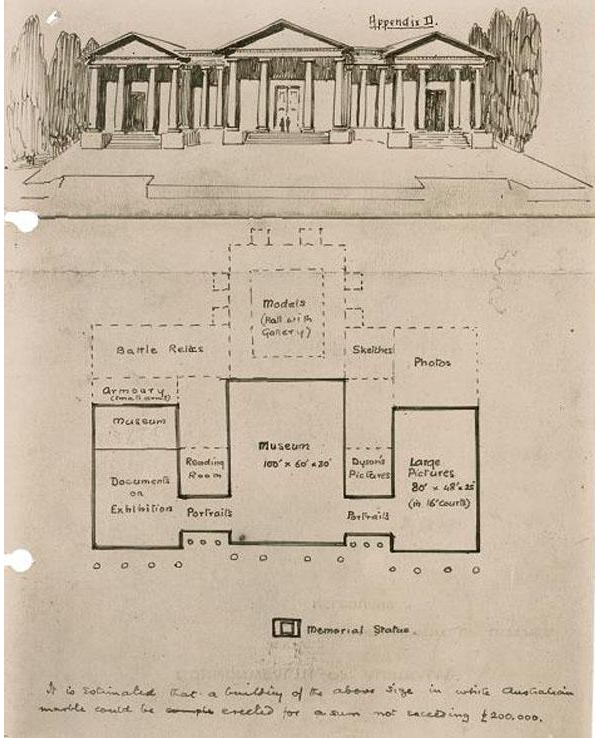

C.E.W. Bean’s building plan

C.E.W. Bean’s 1919 sketch shows that he envisaged the Memorial to be Greek in style, with exhibitions of armour, battle relics, photographs, documents, and art. A separate space is dedicated to the display of artworks by Will Dyson, whose work Bean esteemed highly for its depiction of the Australian Imperial Force. The text at the base of the sketch suggests that the building could be built in white Australian marble for £220,000. The Australian War Museum Committee discussed Bean’s sketch at its meeting of 31 July 1919, along with the proposed operations of the Memorial.

[AWM170 1/1 – 1 folio – building plan – report of 31 July 1919, appendix II]

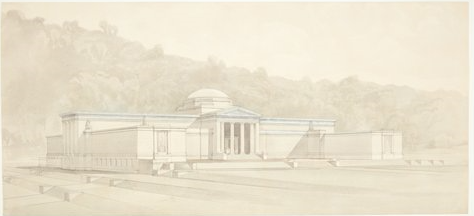

John Crust’s architectural competition entry: perspective drawing south west of building

The construction and siting of the Memorial were approved in 1923, and an international architectural competition to design the building was launched in 1925. Entries were to include plans for a Hall of Memory to house a Roll of Honour listing the names of the fallen. John Crust’s entry shows a modest building in the classical style, nestled at the foot of Mt Ainslie.

[AWM Plans Collection, Drawer 1, Folder 1, Item 1: RC11580]

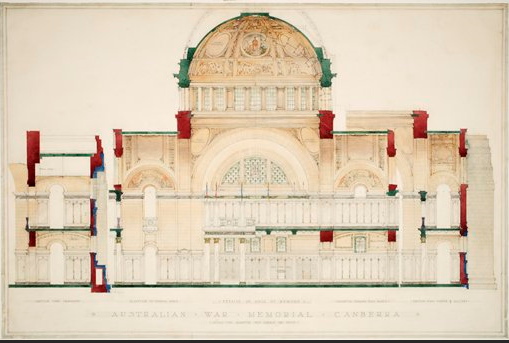

Photograph of the elevation of Emil Sodersteen’s design

Sydney-based architect Emil Sodersteen’s design was praised by the competition adjudicators for its expressiveness of purpose and restraint. After the competition closed in 1926, the adjudicators found that no entry met the competition conditions, and only Crust’s entry could be built within the approved sum – as he had proposed that the Roll of Honour be inscribed within cloisters around commemorative courtyards, rather than in a Hall of Memory as requested. Crust and Sodersteen were asked to work together to combine Crust’s proposal for the Roll of Honour with Sodersteen’s solemn and elegant style.

W.H. Buck’s architectural competition entry: details of Hall of Memory

W.H. Buck’s entry, which proposed an elaborately decorated dome within the Hall of Memory, contrasts with the more restrained designs of the Memorial’s architects John Crust and Emil Sodersteen.

AWM Plans Collection, Drawer 1, Folder 1, Item 2: RC10068

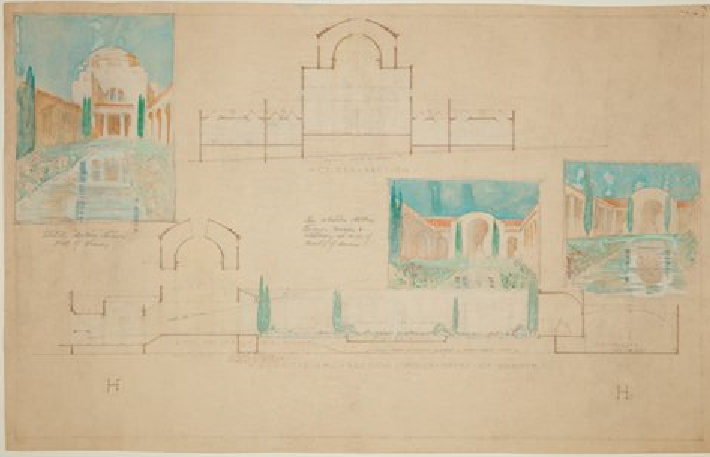

Longitudinal section through Court of Honour – Architectural drawing ‘H’

As John Crust and Emil Sodersteen worked in 1927 to develop a joint design for the Memorial, they produced a series of sketch plans presenting several schemas for the Memorial – some with multiple garden courtyards, and with alternate locations for the Hall of Memory. Initially, they proposed that the Hall of Memory be located to the front of building, so that visitors passed through it to enter the Garden Court. This idea was reversed in the final plan, with the Hall of Memory placed to the rear of the building.

AWM plans collection, Drawer 4, Folder 2, Plan H, Item 2: RC04365

Photograph of Sodersteen and Crust, March 1928

This extract from the Memorial’s newspaper clippings collection shows a photograph of John Crust (left) and Emil Sodersteen (right) from The Age dated 29 March 1928.

[RC11573.001]

1928 Designs, Elevation to Prospect Place

Architects Emil Sodersteen and John Crust prepared a set of architectural drawings for submission to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works in March 1928. The drawing shows the proposed entrance to the Memorial from Prospect Place, now Anzac Parade. The committee’s report approving the building was accepted by parliament in June of that year.

[AWM Plans collection, Drawer 3, Item 24: RC11580.008]

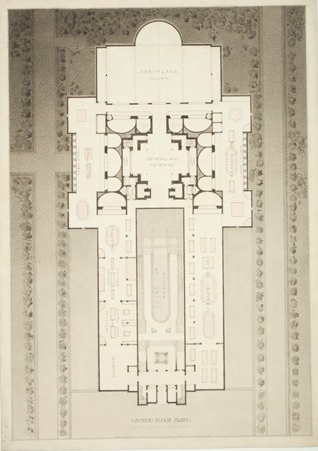

Ground floor plan

Part of the set prepared by Sodersteen and Crust for parliamentary approval, this drawing details the exhibition spaces to be located on the ground floor. The galleries are arranged by conflict, with spaces for dioramas of major battles, and a hall for the display of aircraft. The dioramas had been part of Bean’s vision for the Memorial since 1918. Through conversations with Dyson, Bean developed the idea that the dioramas would be works of art in their own right.

[AWM Plans collection, Drawer 3, Item 11: RC11580.004}

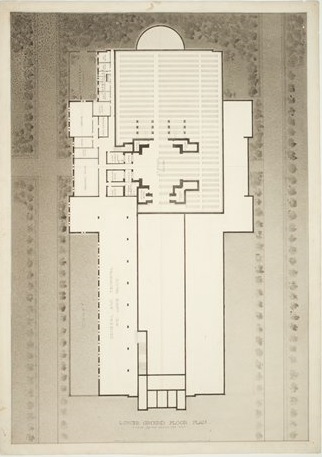

Lower ground floor plan

Part of the set prepared by Sodersteen and Crust for parliamentary approval, this drawing shows the archival storage provided on the lower ground floor. For Bean, the archive was crucial for allowing the stories of the men and women of the Australian Imperial Force to be told in their own words. Bean had advocated for the establishment of the Australian War Records Section, which was formed in May 1917, headed by Lieutenant John Treloar. The War Records Section came to collect not only written records, but war relics, photographs, and art for the future Memorial. In 1920, Treloar became the Director of the Australian War Museum and from then spearheaded the difficult project of bringing the vision of an Australian War Memorial into reality.

[AWM Plans collection, Drawer 3, Item 12: RC11580.005]

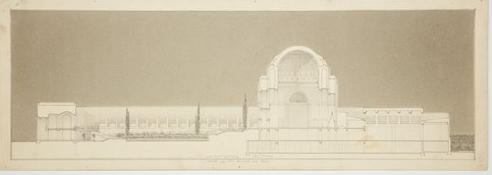

Longitudinal section through Court of Honour

Sodersteen and Crust’s final design, approved by parliament in 1928, provided for a single garden courtyard with the Hall of Memory to the rear of the building, as seen in this cross-section through the Court of Honour and the Hall of Memory. The 1928 plans, substantially describe the form of the Australian Memorial Building as it was built in 1941, and as it appears today.

AWM Plans collection, Drawer 3, Item 26: RC11580.009

Perspective drawing of the Garden Court

This drawing by John Crust, made in 1928, shows plans for the Garden Court (now Commemorative Courtyard). Close examination reveals not one but two figures looking into and reflected from the central pool. After parliamentary approval of the plans in 1928, there were hopes that the Memorial would be built by 1931. However, the Great Depression caused significant delay. There were constraints on government spending, and debate about whether it was better to commemorate those servicemen who had given their lives or support those who had returned and were out of work.

[AWM Plans collection, Drawer 3, Item 6: RC03668]

Photograph of the partially completed Memorial

This newspaper clipping shows the Memorial under construction. Due to the Depression, work on the building was divided into two stages: storage and exhibition spaces would be constructed first, the Hall of Memory and cloisters later. Building commenced in February 1934 and staff started to move the collections in from November 1935 as the first stage neared completion. The flock of sheep highlights the way in which the vision for Canberra as an ideal city and national capital would remain a work in progress for years to come.

Emil Sodersteen’s 1936 perspective drawing with higher dome and open front

In 1935 Sodersteen travelled overseas for the first time, returning in early 1936 with renewed enthusiasm to prepare plans for the completion of the Memorial and the landscaping of its grounds. He proposed substantial increases to the height of the dome, and for the site, verdant tiered gardens punctuated by fountains. Bean was in favour of the new design but Treloar was strongly opposed, concerned that the new design would exceed budget and cause delay.

[AWM plans collection, Drawer 5, Item 4: RC11391]

Drawing prepared by John Crust comparing the 1928 and 1938 designs by overlays

Sodersteen’s 1936 proposal precipitated several years of tense discussions about how to complete the building, with Crust at one stage writing to Treloar, “I would like to get the work finished so that I can be rid of the constantly recurring arguments between Sodersteen and myself”.

While at times Bean and a number of board members supported Sodersteen’s design, Treloar was consistent in pressing for the original design, fearful that further delay and rising costs might prevent the completion of the building. In this drawing Crust uses an overlay of tracing paper to compare the 1928 design with the alternate higher dome. Impasse over the design led Sodersteen to resign in November 1938 and Crust assumed responsibility for completion of the building.

[AWM plans collection, Drawer 5, Item 38: RC11580.040]

Aerial view of the Australian War Memorial from the north-west

From the work being undertaken on the grounds, it is thought that this photograph of the Memorial was taken just before the official opening on 11 November 1941.

It would take another three years for the Memorial to be opened to the public. Even then, the building was incomplete – the Hall of Memory was not officially opened until 1959 and the First World War panels of the Roll of Honour were installed later yet, in 1961.

Photograph of official guests at the official opening of the Australian War Memorial, 11 November 1941

The official guests at the 1941 official opening included the Governor-General Lord Gowrie (front row, third from right) and Prime Minister Robert Menzies (left of flagpole, second row from back).

This ceremony was divided into two parts. While the board originally planned for a non-denominational ceremony, Roman Catholic church rules prevented this. A compromise was negotiated, whereby the religious component of the ceremony concluded before the two-minute silence at 11 am. After this, Catholic dignitaries, schoolchildren, and individuals joined the gathering to participate in a secular “national ceremony”.

[P01313.001]

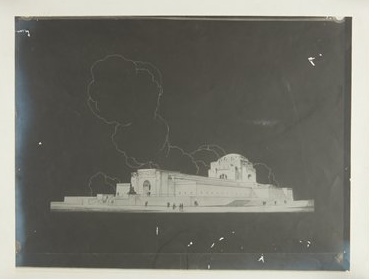

Sodersteen’s drawing of the building

This photograph records Emil Sodersteen’s drawing depicting a faint cloud above the planned Australian War Memorial, which may be interpreted as representing the spirits of the fallen descending to the Memorial.

Treloar may have recalled this image in 1941 when responding to Bean’s letter describing the inauguration ceremony. According to historian Michael McKernan, Treloar “suggested to Bean that he must have felt encompassed ‘by a great cloud of witnesses’” with whom they had both worked closely.

[AWM Plans Collection, Drawer 3, Item 3: RC11580.001]