The Memorial in Landscape

The Australian War Memorial acknowledges the Ngunnawal people who are the traditional custodians of this land. The Memorial would also like to pay respect to their Elders, past and present, and the Elders from other communities viewing this exhibition.

For the newly federated nation of Australia, communicating the Australian Imperial Force’s First World War experiences through a memorial located on home soil was a critical assertion of national identity.

The Memorial occupies a prominent position in Walter Burley Griffin’s design for an ideal capital city, located on a majestic line of sight extending from Mt Ainslie to Parliament House. The first plans for the Memorial grounds, prepared in 1936 by architect Emil Sodersteen, were elaborate and extensive. Sodersteen proposed cascading garden terraces at the entrance to the Memorial, and water features and verdant plantings extending along Griffin’s land axis well beyond the current Memorial grounds.

While political and economic challenges forced the reassessment of these early ambitions, significant development over recent decades has allowed for expansion of the Memorial buildings, and today the Memorial grounds are host to commemorative ceremonies, sculptures, plaques, and gardens.

The Memorial in landscape is the third part of the exhibition series A home on a southern hill, presented online to mark the 80th anniversary of the Australian War Memorial building, which was inaugurated on 11 November 1941.

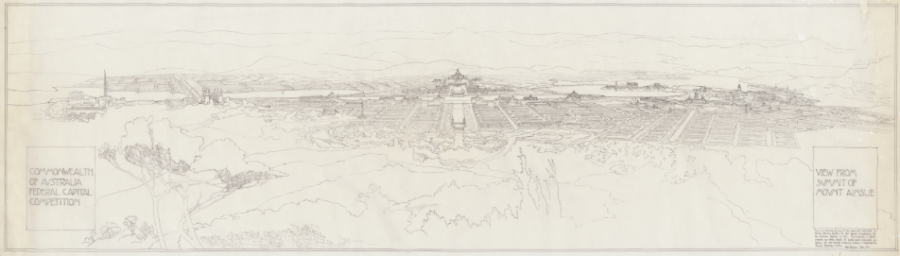

View from the summit of Mount Ainslie

When Charles Bean selected the site for the Memorial in 1919, Canberra was little more than an assortment of sheep grazing paddocks. American architect Walter Burley Griffin had won an international competition to design Canberra in 1912, envisaging the new capital as an important, efficient, sociable city in harmony with the natural features of the land. His design – exquisitely presented by his wife and fellow architect Marion Mahony Griffin – was structured around radiating axes connecting natural landmarks.

This tracing of Marion Mahony Griffin’s View from summit of Mount Ainslie, shows how the Memorial site is at one end of a land axis that runs along a broad avenue to Parliament House. This majestic line of sight ensures that those with the authority to commit their country to conflict look upon an inescapable reminder of the consequences of war.

This tracing was made by Canberra town planner Peter Harrison after he discovered the Griffins’ competition entry drawings in storage in 1955.

[Tracing by Peter Harrison of Federal Capital Competition panel submitted by the Griffins, “View from Summit of Mount Ainslie”, 1956, Harrison Papers, National Library of Australia, MS 8347/6/44, © Peter Harrison]

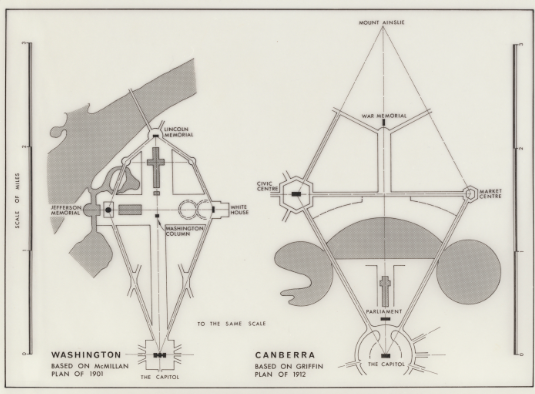

Schematic comparison of Washington and Canberra

Canberra town planner Peter Harrison prepared this diagram in order to demonstrate the parallels between Canberra and Washington, and to explain how the influence of the gardens of Versailles extended to Canberra.

When it came to designing Canberra, Griffin looked to the ideas of City Beautiful and the work of leading American architect Daniel Burnham for inspiration. Daniel Burnham had been commissioned to revitalise Washington DC in 1901, and did so by substantially restoring the original 1791 design by Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant, whose geometric plan allowing for reciprocal lines of sight from various monuments was strongly influenced by his childhood home of Versailles.

[Peter Harrison's schematic comparison of Washington and Canberra, 1956, Harrison Papers, National Library of Australia, MS 8347/5/49/4, © Peter Harrison]

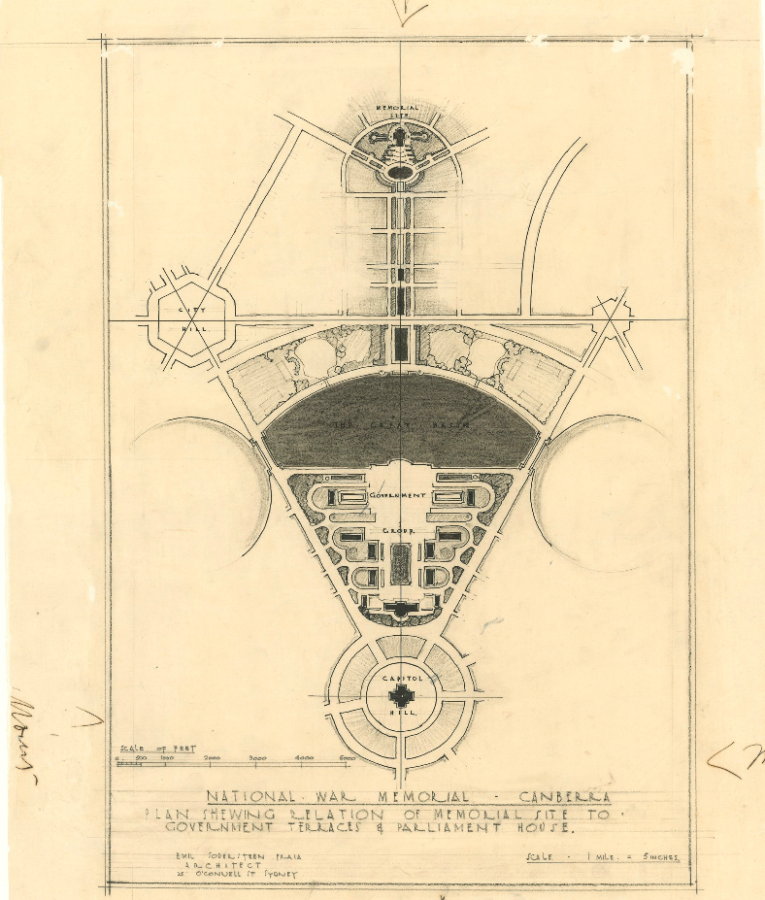

Plan showing axis of the Memorial site to government terraces and Parliament House

Before the First World War, Walter Burley Griffin intended the site on which the Memorial now stands to house a public meeting place, with a recreational park and semi-circle of commemorative structures to the rear. As designs for the building came before the Parliamentary Works Committee in 1928, Griffin supported the construction of the Memorial in this location.

Work on the building was delayed by the Great Depression and it was not until 1934 that the architects of the Memorial, John Crust and Emil Sodersteen, were approached to design the landscaping of the Memorial grounds. After years of animosity between the two, Crust allowed Sodersteen to design the site on his own, writing that “preparing a joint design with Sodersteen would be irritating and a waste of time”.

Sodersteen extended his brief, designing not only the Memorial grounds, but plantings and water features along the line of sight between the Memorial and Parliament House.

[RC09901]

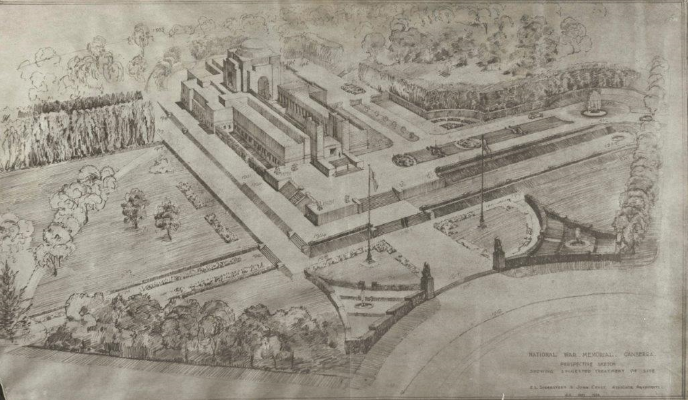

The first proposed landscape treatment, 1936

Emil Sodersteen was commissioned to design the Memorial grounds in 1934, and the following year travelled to Europe and America to study developments in landscape design. Impressed by the oak and beech hedges, and rows of chestnuts, oaks, and poplars at the Luxemburg Gardens and Versailles, he returned envisaging elaborate formal gardens with tiered terraces, punctuated by fountains and flagpoles, cascading down to Anzac Avenue, with water features and plantings continuing towards Parliament House – a plan requiring a heavy financial commitment to build and maintain.

The Lone Pine had been planted in 1934, and Sodersteen used its location as the basis of a series of paths around the building that would lead to two long water gardens extending in a cruciform shape from the building.

[RC01648]

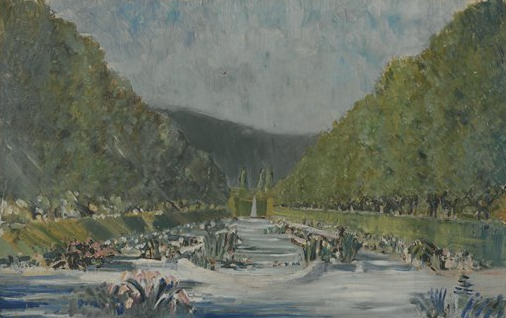

Emil Sodersteen, The Water Garden, oil on board, 1936.

Sodersteen envisaged water gardens to the east and west of the Memorial building, on either side of the domed Hall of Memory. On the eastern side, a stepped water garden between two lines of trees was to lead to a fountain from which one could turn to see the framed dome of the Memorial – the Water Garden depicted in this painting. On the western side of the building was to be a long pool, again between two lines of trees, designed “to catch the afternoon reflections of the Dome in its waters”.

Sodersteen paid great attention to the design of the gardens and painted this image to capture the colours and perspective of looking towards the pool away from the Memorial building. In his view, “the effect of the building could be ruined from the artistic point of view should the site not be given proper consideration both in regard to the general layout and also with regard to the types of trees and other plantings chosen”.

The Memorial Board liked the long water garden design, and, when requesting John Crust and Tom Parramorre to prepare a simpler, less expensive design in 1940, asked for its inclusion.

[ART92900]

Revised landscape treatment, 1938

After Sodersteen’s landscape proposal was submitted in 1936, Memorial Director Treloar waited another two years for him to supply an estimate of costs. The estimate came in at £55,000. Having just emerged from the Great Depression, and with another world war brewing, Sodersteen was asked to submit a less expensive design, contained to the Memorial’s grounds.

Attributed to Sodersteen and Crust, this drawing is a significant departure from Sodersteen’s 1936 plan, especially in its asymmetry.

In October 1938 Sodersteen presented detailed, costed plans for the staged development of tiered terraces that would also serve as a first stage of his 1936 plan. After Sodersteen’s resignation, this plan was put aside.

[RC04371]

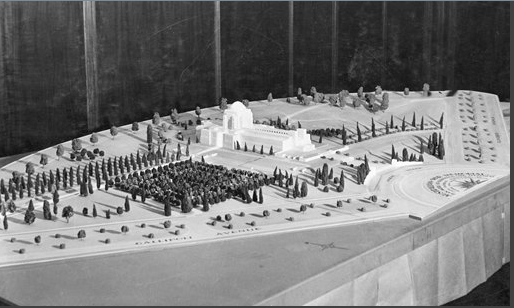

John Crust and Tom Parramore’s proposed site treatment, 1940

With the opening of the Memorial planned for Anzac Day 1941, John Crust and Sydney-based landscape designer Tom Parramore were employed in 1939 to plan the Memorial grounds.

This model was built as part of the site design proposal submitted to the Memorial in 1940. It was created by Memorial staff member Stanley Pearl, who is today well-known as the trench artist “Sapper Pearl”.

The model shows a square arrangement of trees, with paths to the Lone Pine at the south-western point. Before approving the design, the Board requested that the tree-lined road leading from the west be replaced with a water garden similar to that earlier proposed by Emil Sodersteen. With funds lacking during the Second World War, no element of the proposal was built.

Instead, the site was levelled and the Memorial was opened in 1941 surrounded by a bare paddock with the bush-covered Mount Ainslie to the rear – a setting described by the press as “more typically Australian than any of the city memorials”.

[XS0099]

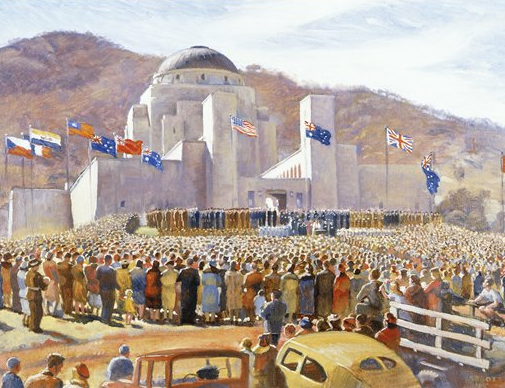

Harold Abbott, VP Day, Canberra, oil on canvas board, 1945

On 15 August 1945 Australia celebrated Victory in the Pacific; the Second World War was finally over. This painting records the celebration held at the Australian War Memorial marking the victory. The simple treatment of the grounds affords the space for a significant ceremony immediately in front of the Memorial. The flags of allies fly alongside the Australian flag above the large crowd, while Mount Ainslie rises high above the building.

With the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, the expansion of the original Memorial building was anticipated even before it was officially opened in 1941. The building was first expanded to house Second World War galleries in 1971, followed by the development of a precinct at Mitchell for large technology items and conservation, and additional buildings in Campbell.

[ART22923]

Flanders Memorial Garden Dedication, Smoking Ceremony

Today, the Memorial grounds are host to commemorative ceremonies, and house many sculptures, plaques, and gardens.

In April 2017, the Flanders Memorial Garden was dedicated to the memory of those 12,000 Australians who lost their lives in Belgium in 1917. During the dedication ceremony, soil from battlefields and war cemeteries across Flanders, and significant military heritage sites in each Australian state, was placed in the garden. A traditional smoking ceremony was held by Ngunnawal elders to cleanse the site and bless the soil.

[AWM2017.4.85.91]

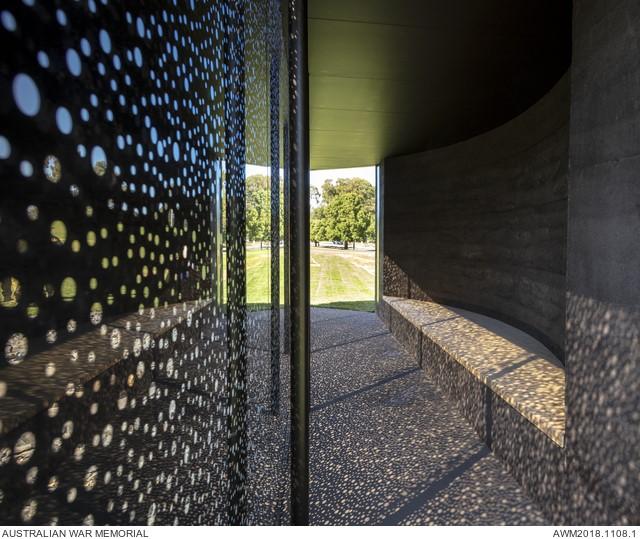

The contemplative space of For Our Country

Since its dedication in March 2019, visitors to the Memorial have been able to enter and sit within the contemplative space of For Our Country, which recognises the military service and ongoing sacrifice in defence of Country of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The award-winning sculptural pavilion was designed for the Memorial’s sculpture garden by artist Daniel Boyd, a Kudjala/Gangalu/Kuku Yalanji/Waka Waka/Gubbi Gubbi/Wangerriburra/Bandjalung man from North Queensland, and Edition Office architects. Learn more here about the rich symbolism of this sculpture: https://www.awm.gov.au/visit/exhibitions/forourcountry

[AWM2018.1108.1]