To Heal the Nation

C.E.W. Bean made a singular contribution to the recording of Australia’s history and to Australia’s sense of itself as a nation. As Australia’s official war correspondent during the First World War, he accompanied the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) into action on the Gallipoli Peninsula and in Europe, all the time making meticulous notes that would inform Australia’s official war history. He conceived the Australian War Memorial in 1916 after witnessing the carnage on the Western Front, determined that the sacrifice and contribution of the men of the AIF be remembered and understood in their homeland.

While deploring the terrible loss of life, Bean believed that the courage and determination of the men of the AIF was meaningful. For Bean, their actions demonstrated the nature and value of the Australian character, forming a foundation stone with the strength to support and inspire the greatest of endeavours. Through his writing and the Australian War Memorial, he presented their story as a basis for national pride and identity that resonates to this day.

To heal the nation considers how C.E.W. Bean’s experiences shaped his vision for the Australian War Memorial and reflects on the nature of commemoration, looking at how tradition, ceremony, and beauty assist us in approaching war and loss.

To heal the nation is the second part of the exhibition series A home on a southern hill, presented online to mark the 80th anniversary of the Australian War Memorial building, which was inaugurated on 11 November 1941.

George Lambert, Charles E W Bean, 1924, oil on canvas, 90.7 x 71.1 cm

This portrait of Charles Bean was painted by George Lambert in 1924, when Bean was 44 years old. By this time, Bean was known for his work as Australia’s official war correspondent during the Great War, and was working towards the establishment of the Australian War Memorial while writing and editing the 12-volume Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918.

Reflecting his background as a journalist, Bean had an eye for the stories of individuals as well as the larger themes of the war. By including these stories he wrote a new style of military history which showed the war was about the actions of enlisted men and officers as much as the commands of generals and politicians.

Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean and his brother Jack Bean

C.E.W. Bean’s family had a strong influence on his career and vision for the Australian War Memorial. His father, Edwin, an esteemed and well-connected school principal, provided him with a classical education. His mother, Lucy, instilled in him the habit of diary keeping, which he took to the war. His younger brother, Jack, shown here, suggested that Charles should be a war correspondent when the boys were in their teens – a suggestion that he attributed to his brother’s “intense interest and pride in the British Army and Navy” and “great visualising power of imagination”.

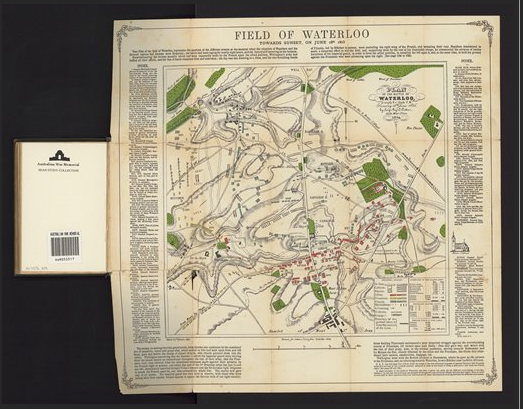

A Voice from Waterloo by Edward Cotton

When Bean wrote his recollections of the development of the Memorial, the first things mentioned are boyhood holidays to the battlefield of Waterloo, during which the family stayed at a hotel established by Edward Cotton, who had been sergeant major of the 7th Hussars. Bean describes his fascination with Cotton’s collection of relics from the battle, and he and his brother “pick[ing] up imagined relics in the fields … probably bits of farm harness – to make our own museums”.Bean kept this copy of Edward Cotton’s history of the Battle of Waterloo, which had been his father’s, his entire life. The frontispiece includes the phrase “Facts are stubborn things”. Bean was determined to report the truth, seeking to compare multiple accounts of battles to more fully inform his understanding.

Graves in Shrapnel Gully cemetery, Gallipoli peninsula, November 1915

Soldiers on Gallipoli made many personal gestures of commemoration in the days preceding the evacuation in December 1915. Bean photos of the gravesites and observed in his diary, “The men aren’t sorry to leave – not most of them. They regret leaving all their comrades buried here, and the number of demands for timber for graves has been enormous.”

Bean’s efforts to record the activities of the AIF – in writing, photographs, paintings and sketches, and by collecting relics – foreshadow the activities of the Australian War Records Section, and the ongoing activities of the Australian War Memorial.

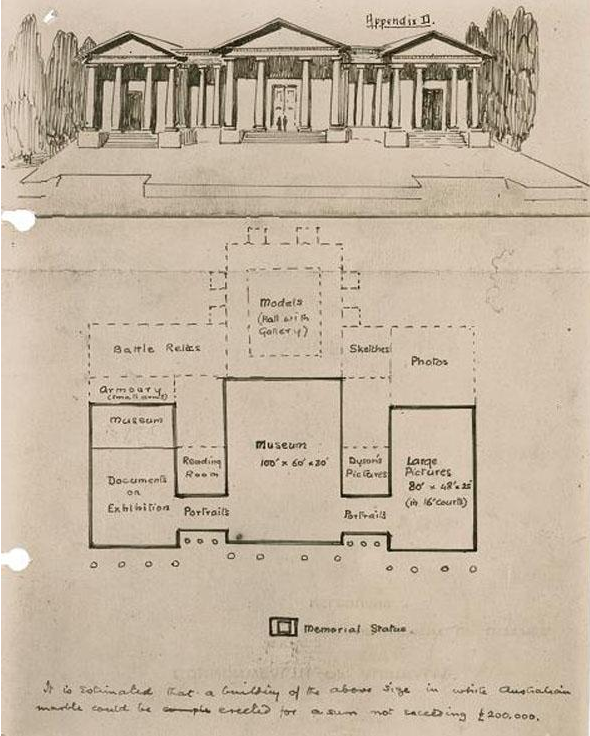

CEW Bean’s 1919 sketch for the proposed Australian War Memorial

C.E.W. Bean first conceived the Memorial as he witnessed the horrors of the Western Front in 1916 and work towards the future Memorial began almost immediately, through the collection of war relics and, in May 1917, the establishment of the Australian War Records Section.

After the war, planning for the building began in earnest. Bean envisaged the Memorial to be Greek in style, with exhibitions of battle relics, photographs, documents, and art.

AWM2017.7.114

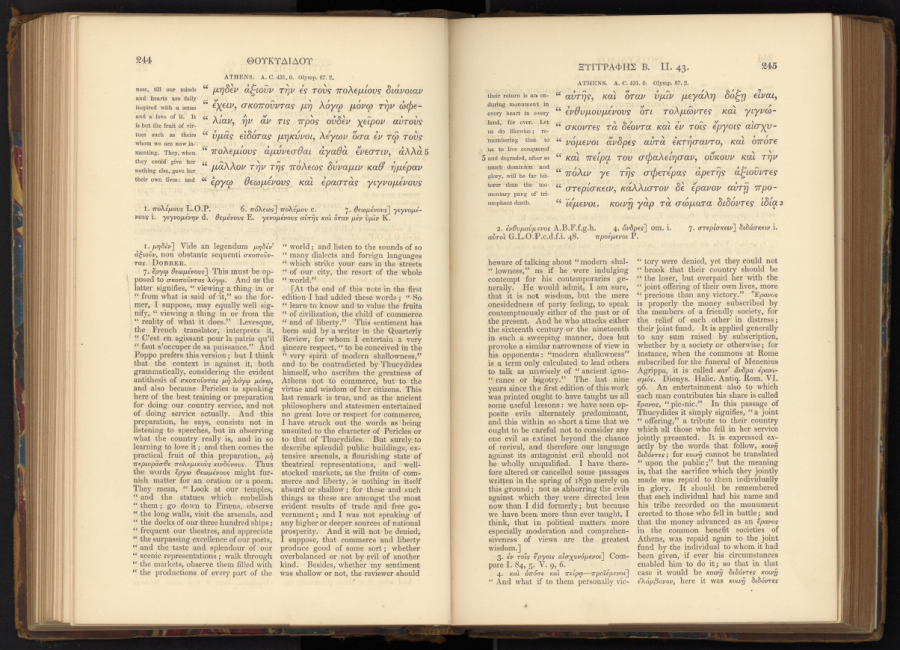

Bean’s textbook edition of History of the Peloponnesian War

In the years following the First World War, many looked to the classical world to give context and meaning to tragic loss, and for suitable forms of commemoration. Bean was educated in the classics and drew nuanced parallels between the stories of ancient Greece and the experiences of the AIF, linking the youthful democracies of Australia and Athens of the 5th Century BC. The English-language commentary in Bean’s textbook edition of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War proves Peter Londey’s theory that the idea for the Roll of Honour came from the Athenian practice of listing their war dead – “the sacrifice which they jointly made was repaid to them individually in glory … each individual had his name and his tribe recorded on the monument erected to those who fell in battle.”

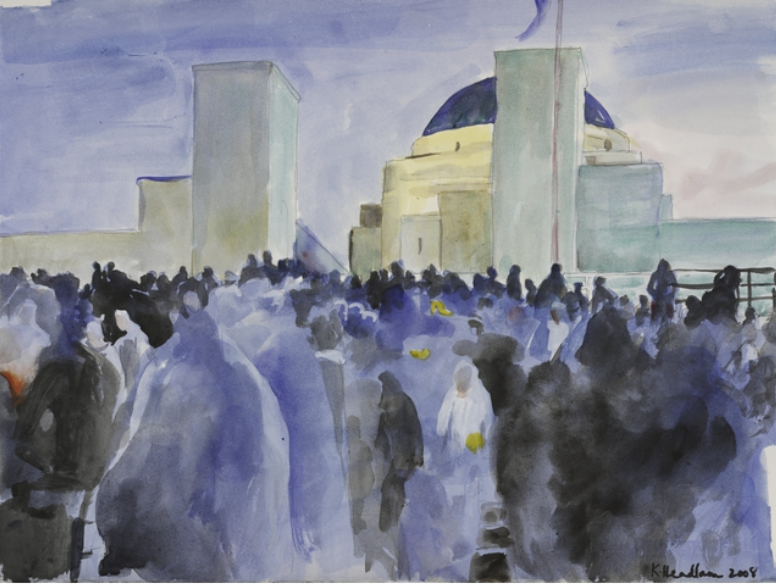

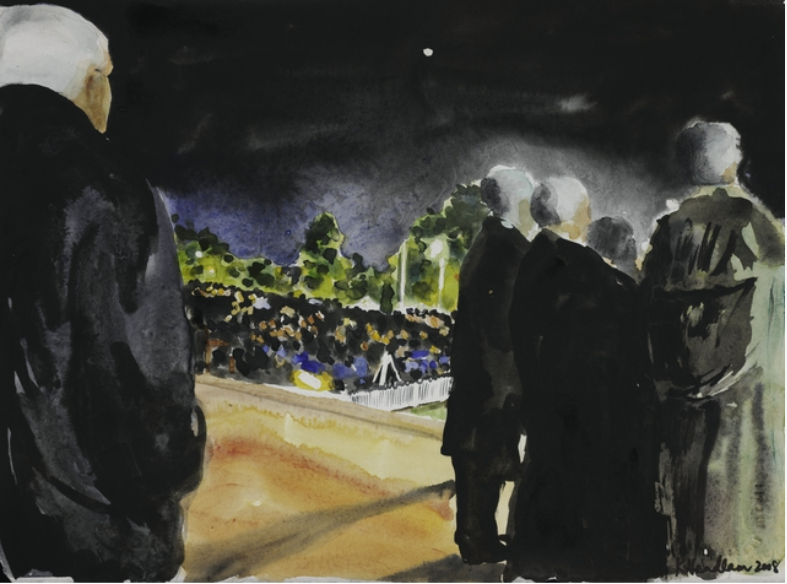

Kristin Headlam, Sketch for 2008 Dawn Service Commission, 2008, watercolour and pencil on paper, 28.5 x 38 cm

Artist Kristin Headlam shows individual forms within the crowd gathered at the Australian War Memorial for the 2008 Dawn Service in the half-light of dawn. The timing of the ceremony is based on the fact that the Gallipoli landing commenced at dawn – a time of day long-favoured for attacks. For many who attend, enduring the discomfort of a cold, early start is a means of showing respect to those who have served or fallen. The landing at Anzac Cove on 25 April 1915 has been marked by ceremonies and services in Australia each following year. By the late 1920s it had become a national day of commemoration and a public holiday in every state. Anzac Day was first commemorated at the Australian War Memorial in 1942, following the Memorial’s opening on Remembrance Day 1941.

ART93387

Kristin Headlam, Sketch for 2008 Dawn Service Commission, 2008, watercolour and pencil on paper, 29 x 39 cm (ART93388)

In this sketch by artist Kirstin Headlam recording the 2008 Dawn Service, we are able to make out some of the individuals attending – those depicted are neatly and warmly dressed, and are silver-haired. The age and number of people attending commemorative services has changed in recent years. In 1977 around 2,000 people attended the Memorial’s Dawn Service. Crowds steadily grew through the 1980s, reaching 12,000 in 1990. This decade, which features the centenary of the First World War, has seen a dramatic increase in attendance, with a record 128,700 people attending the Memorial’s 2015 Dawn Service.

David Jolly, Flag, 2015, oil on glass, 76 x 50 cm

Each year, thousands attend Anzac Day ceremonies. In 2015 the Australian War Memorial commissioned Melbourne-based artist David Jolly to attend the centenary Anzac Day Dawn Service on Gallipoli, which some 15,000 Australians travelled to attend.

This painting depicts the Australian flag at half-mast in a traditional sign of remembrance.

David Jolly, Pilgrims, 2016, oil on glass, 76 x 50 cm

For many Australians visiting Gallipoli is a form of pilgrimage. In this painting David Jolly depicts the crowd leaving the Anzac Commemorative Site. They are weary, having camped out overnight to attend the Dawn Service, but most will nonetheless walk up a steep track to attend the Lone Pine ceremony. The camouflaged Turkish soldier in the foreground indicates the dedication of the Australians who travelled to the site in the face of threats of terrorism, and the ongoing hospitality of the Turkish nation.

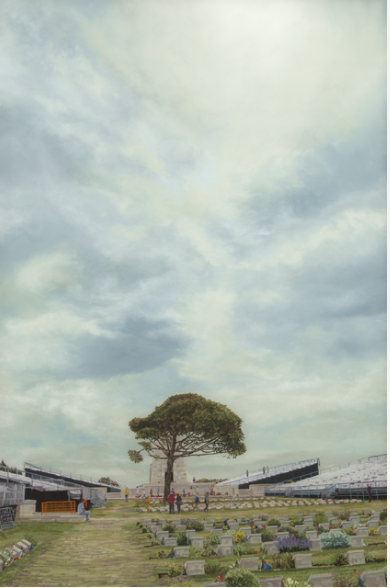

David Jolly, Plateau, 2016, oil on glass, 76 x 50 cm

The Lone Pine Memorial commemorates those Anzacs with no known grave, and those who died and were buried at sea after the evacuation. This painting depicts the Lone Pine Cemetery and Memorial the day after the 2015 Anzac Day centenary commemorations. Artist David Jolly has underlined the melancholy of the site, the empty seats echoing the gravestones as markers of those no longer present. The seating also draws attention to the infrastructure and behind-the-scenes work required to support commemorative events.

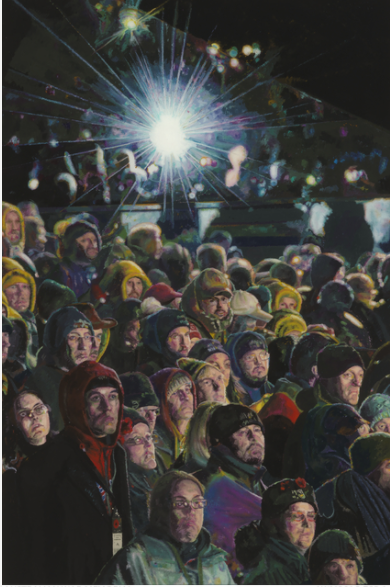

David Jolly, Centenary, 2016, oil on glass, 76 x 50 cm

Artist David Jolly depicts the crowd gathered at Gallipoli in the hours before the dawn ceremony, many wearing warm items of clothing featuring the distinctively Australian colour of wattle-yellow. The camera flash in the background highlights the way in which commemorative events are publicly broadcast spectacles. While key ceremonies were previously broadcast by radio, commemorative events such as the Memorial’s Last Post Ceremony are now broadcast live each evening via webcam.

Fiona Silsby, Anzac Day Dawn Service 2012 at the Australian War Memorial, 2012

While the Anzac Day Dawn Service is a public gathering that attracts thousands of people, the ceremony is also characterised by personal reflection.

Fiona Silsby recalls taking this photo at one of the first Dawn Services that she attended as a Memorial photographer. The public ceremony had ended and the crowd was moving towards the Hall of Memory. While most people gathered in small groups to converse or read the messages on wreaths, this man stood in contemplation at the Stone of Remembrance. Situated in front of the Australian War Memorial, the stone is inscribed with the words “Their name liveth for evermore”.