| Places | |

|---|---|

| Accession Number | RELAWM20434 |

| Collection type | Technology |

| Object type | Communications equipment |

| Physical description | Bakelite, Copper, Glass, Rubber, Solder, Steel, Wood |

| Location | Main Bld: World War 2 Gallery: Gallery 2: Fall Sing |

| Maker |

Loveless, Max Lyndon |

| Place made | Timor |

| Date made | 1942 |

| Conflict |

Second World War, 1939-1945 |

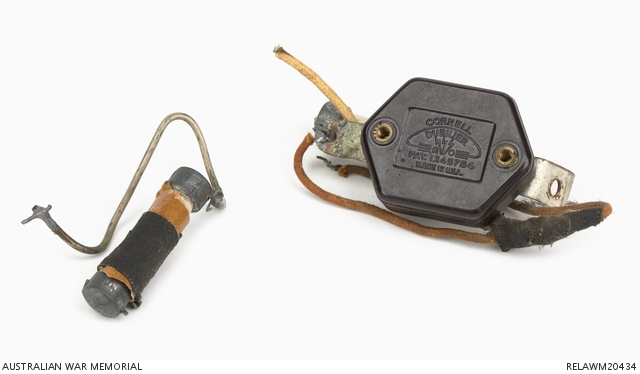

Radio transceiver, 'Winnie The War Winner': Signaller Max Lyndon Loveless, 2nd Australian Independent Company

Hand made transceiver set which was constructed from parts obtained from a commercial Portuguese wireless set, parts from a 101 and 109 Australian Wireless sets, and salvaged parts from the demolished wireless station at Atamboea in Timor.

They consist of (clockwise from left rear): the high voltage power suppy, the switching unit, the tuning coil and condensors, and the power amplifier. The power supply unit uses three General Electric pyranol capacitors and two 4307A type valves as well as a transformer (probably salvaged from the wireless station at Atamboea), and a switching unit (ditto). The tuning coil appears to include a length of copper wire wound round a length of bamboo and a tuning device salvaged from an AWA commercial set. The whole power amplifier assembly is soldered onto a kerosene tin.

The units were connected in sequence (see image 060349) to form a improvised transceiver which could transmit and receive morse code between Timor and Darwin.

This improvised transceiver, nicknamed 'Winnie the War Winner', was built from salvaged parts on Timor by Sparrow Force. It was used to contact Darwin on 20 April 1942, alerting them to the fact that parts of Sparrow Force and the 2nd Independent Company commandos were alive and still operating against the Japanese in Timor. These men hadn’t been heard from since 23 February 1942, after the Japanese landings on Timor, and it had been presumed they were either captured or dead.

In reality members of the Australian force had managed to escape into the hills south of Dili in Portuguese Timor and commenced a guerrilla war against the Japanese. They were later joined in early March by the survivors of Sparrow Force HQ force. The men were well-armed, but lacked a radio powerful enough to reach Australia.

A central group of signals personnel – a combination of Corporal John Sargeant and Lance Corporal John Donovan from 2/1 Fortress Signals, and Signalmen Keith Richards and Max Loveless from the 2nd Independent Company under the leadership Captain George Parker (8 Division Signals) worked for almost two months to construct a working transceiver. Signalman Max Loveless had been a radio technician with ABC radio 7ZL in Hobart before he enlisted.

The task of building the transceiver was taken on by Loveless, who stripped parts from other sets and assembled the transceiver, using accumulators and a tuning crystal they had salvaged. A 109 set provided the pieces for an amplifier for the oscillator, while a commercial AWA set supplied the tuner. Loveless consulted a Portuguese radio manual to determine the colour coding for wiring the condensers, and hand-built items such as coils by winding copper round bamboo; used remelted solder and remade valve sockets for the type 4307A valves salvaged from the 109 set. The power amplifier was soldered onto a kerosene tin. This difficult work was conducted in windowless shed.

Eventually in mid-April the four parts of the set were connected up and Loveless sent a transmission. Nothing was heard, so they tried again three days later on the 16 April. Again nothing was heard, but in Darwin their morse signals were picked up. Darwin advised all mainland transmitter stations to keep off the air the following night and listen for the signals coming from Timor.

Again Darwin picked up their signal but was suspicious that this was a Japanese hoax. On the next night (20 April) Darwin demanded proof of the commando’s identity, which the Timor men answered correctly and immediately. Australian authorities realised that they still had a force in Timor and had resupplied Sparrow Forces by air within a week. Although they continued to resupply and man the commandos, by the start of January 1943, the army were forced to evacuate the commandos along with their improvised radio.

Damien Parer, fresh from his coverage of the fighting in New Guinea, joined a resupply mission in early December 1942, where he filmed re-enactments of the group ‘constructing’ the radio and ‘contacting’ Darwin. The footage formed an essential part of his film ’Men of Timor’.

The role of 'Winnie the War Winner' became well known throughout Australia when the radio was evacuated with the commandos. Within days, and in multiple (obviously syndicated) newspaper reports, the radio transceiver was described as “a crazy contraption built from scraps of wire and tin and pieces of discarded radio”. But it was much more than that - Corporal John Sargeant in the donor file described the radio in almost mortal terms – “Treat with care – she is our particular pet.”

On the night of 5 December 1943, 'Winnie the War Winner' was featured on a nationwide commercial radio broadcast repeating the morse code it had originally sent from Timor the previous April. Then, on 15 February 1944, the improvised transceiver was handed over to the Military History Section. It was eventually put on display in the Australian War Memorial in 1959.

The name 'Winnie the War Winner' appears to have two sources – one source has it named after a popular but misogynist and dated ‘Australian Women's Weekly’ cartoon of the period drawn by press artist Ron Vivian. But the commandos themselves contend that the radio was named in honour of Winston Churchill.