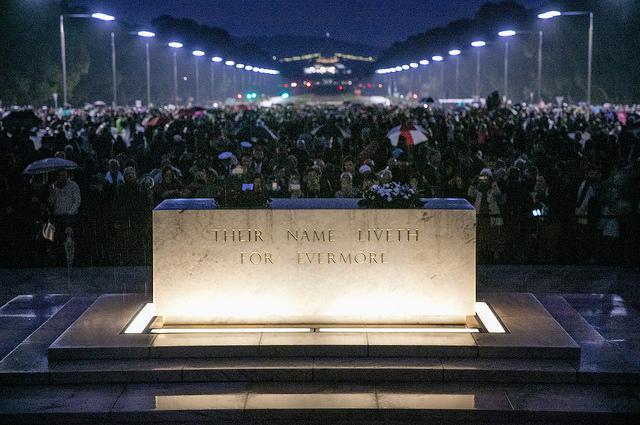

Anzac Day 2017: Dawn Service commemorative address

Anzac Day Dawn Service, Australian War Memorial 2017. See all official photographs.

Seventy-five years ago, Australia braced for impact, from the ever-encroaching conflict of World War II, as it made its way South through the Pacific.

At a desperate low in the Kokoda campaign, stretcher-bearers lugged wounded Australian soldiers for days through strangling, unyielding jungle to reach medical help.

A young Australian Private, Alan ‘Lucky’ Luckel, had his leg blown off at the knee. Historians wrote: ‘His sergeant went charging down the slope where the luckless lad lay. He picked up the little fellow like a babe in his arms and carried him to safety. Luckel sang while the blood from his half-leg reddened the ridge. The stretcher jerked and jolted and jarred as his mates slipped and staggered and stumbled with him around the side of the spur. Until 300 yards later, they buried him in the Kunai grass.1

There’s an old call sign—DUSTOFF—it stands for ‘Dedicated Unhesitating Service to our Fighting Forces’.

That’s what the sergeant and those stretcher-bearers gave Lucky. The very best of their dedicated unhesitating service, in near impossible conditions, up against a vast and highly-trained enemy force. His was a war fought in a deep, dark, life-sucking valley—some say it was a constant fog2—where he couldn’t have known where or how his next step would land.

Twenty years later, in Vietnam, a different sort of DUSTOFF came into its own – the casualty evacuation helicopter. Badly hurt and dying soldiers were airlifted out of enemy fire, treated on-board, and choppered to the nearest field hospital. Many would survive the previously unthinkable.

The war I came to know was in Uruzgan Province, Afghanistan, some five years ago.

One of the ‘New Wars’ 3. Where the enemy don’t wear uniforms. Where violence is organised by insurgents not by states. Where improvised explosive devices are becoming more sophisticated, more lethal and harder to detect. And where families live and children play in amongst it all. It’s no jungle; more like a sharp-edged, ancient and arid landscape.

What injured me on the 23rd August 2012, has taken thousands of limbs and lives before me: many civilian, and too many, unwitting young kids.

I was an Army Combat Engineer. My job was to clear the day’s path of IEDs ahead of the patrol. Instructions came in late one morning to remove a boulder blocking one of the access roads. My mate Mac and I headed to the job. I was out front and got caught unawares on what I thought was familiar and safe ground.

In a violent, hot explosion, the ground beneath me erupted, taking both my legs instantly. Somehow in a state of bewilderment and physical wreckage, bizarre moments of clarity and focus took hold: I found myself trying to do my own first aid, and instructing the men on how to administer the morphine.

Meanwhile my mates wrestled with five tourniquets on what was left of my legs, as they swallowed their own terror and tears. Then came the men and women in the evacuation chopper —the extraordinarily skilled trauma specialists—with their care I got, an unforgettable DUSTOFF.

When we join the services, and go to war, of course we feel a strong sense of duty to our nation and to all Australians. But when we’re out there in a conflict zone, our greatest responsibility is to our mates alongside us. They are the ones we trust with our mission and our lives.

In my own life, I can see the circles of care around me like ripples from a stone dropped in a pond. Family, friends, doctors, nurses, physios, Defence, RSL, Coaches, and team mates. The list is long. Through the peaks and troughs, they connect, making me stronger at the centre, restoring my physical health, my self-worth, and my sense of a future. Self-reliance matters, but it’s not nearly enough.

War hasn’t always returned us well. In the aftermath of so many conflicts, men and women came home to a silent, private suffering borne alone or with their distraught families, friends and neighbourhoods. It has taken a terrible toll and, for some, it’s far from over.

In soldiering and in peacekeeping, we learn an ethic of service to our nation, to one another, and to the communities we seek to unite and rebuild. In return, our nation is learning an ethic of care to our veterans and service personnel whose ripples spread right across Australian life – a true measure of a nation’s decency and worth.

On this Anzac Day, we look back on a century of courage, endurance, mateship and sacrifice. We honour those who have died and suffered through the old and the new wars. And we thank them for all they have engrained in our nation’s heart and way of life.

And, may we as a nation continue to provide those men and women who have served us with the care they need. Dedicated, unhesitating, service, to our fighting force.

A mighty Australian DUSTOFF.

Lest we forget.

1 Johnston, Mark, Stretcher-Bearers: Saving Australians from Gallipoli to Kokoda. UK: Cambridge University Press. 2015. (p231)

2 FitzSimons, Peter, Kokoda. Australia: Hodder. 2004. (p141)

3 Revill, James, Improvised Explosive Devices: The Paradigmatic Weapon of New Wars. UK: Palgrave Macmillan. 2016. (eBook)