The Meagre gains of war

The Treaty of Versailles may have been punitive, but it was small compensation for the 60,000 Australian dead.

By Joan Beaumont

A century has passed since the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919, formally concluding the First World War. The treaty quickly gained a reputation for being excessively draconian and punitive, as it stripped Germany of all its colonies and around 13 per cent of its European territory. It obliged the German defence forces to dramatically disarm and it demanded that massive reparations be paid to the allied powers. Most infamously, the Treaty’s article 231, the so-called “war guilt clause”, declared that Germany and her allies were responsible for causing not only all the loss and damage that her former enemies had suffered during the war, but also for initiating the “aggression” that had caused the war. So draconian were these provisions of the treaty that is often thought that Versailles sowed the seeds of the next great European conflict.

However, it is too simplistic to blame the rise of Nazism and the Second World War on Versailles. For all its harshness, the treaty might have been implemented, had the powers that won the First World War been united in their policies towards Germany in the post-war era. Instead, Great Britain, France and the United States were deeply divided about international security, reparations and war debts, and they failed to provide the cooperative leadership that might have kept the peace. In particular, their failure to prevent the Wall Street stock market crash in 1929 from developing into an unprecedented global economic depression was critical in the Nazis’ seizure of power.

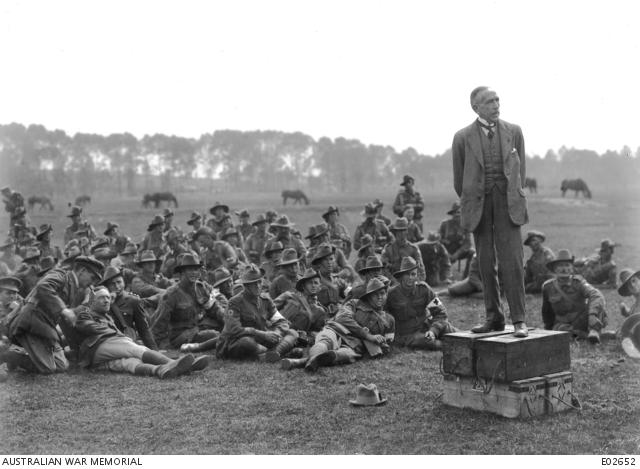

Australia, with its population of around five million, was a bit-part player in these power battles. Yet the brash determination of Prime Minister W.M. “Billy” Hughes ensured that he made a mark on some of the debates and at the Paris peace conference of 1919. This was the first diplomatic conference on this scale (there were 32 governments represented) at which Australia had independent status. Previously, the Dominions of the British Empire had been represented internationally by London or had attended diplomatic meetings as part of a delegation of the Empire.

However, the “blood sacrifice” of the war just ended had changed the balance of imperial relationships; and after some difficult negotiations with the United States and France, Australia (like Canada, South Africa, New Zealand and India) was granted the right to attend the Paris conference. This gave the Hughes the platform on which to pursue what he thought were Australia’s distinctive interests.

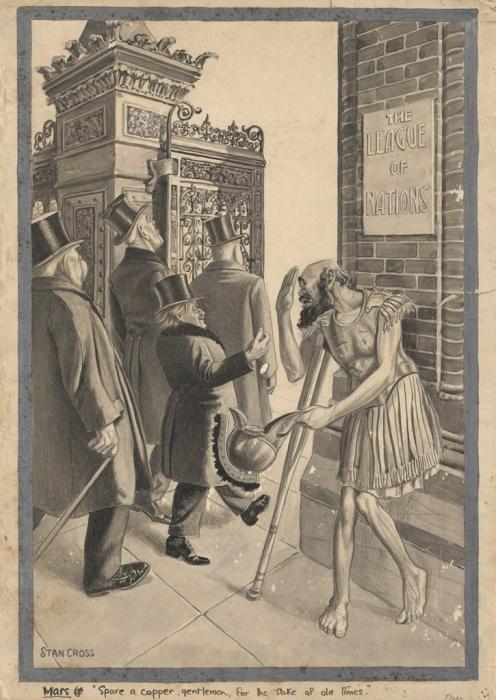

The first of these was post-war control of New Guinea, the Bismarck archipelago, and the Solomon Islands. These German colonial territories had been occupied for strategic reasons by Australian forces in the first weeks of the First World War, and Hughes had no intention of relinquishing them. However, during the armistice discussions in October 1918 the United States president, Woodrow Wilson, had made it clear that he thought that German colonies should not be annexed by the victors, but rather be placed under the control of the new international security organisation that he was championing, the League of Nations.

Hughes’s battles with Wilson about German New Guinea became the stuff of folklore. In one of their meetings on the topic, Wilson challenged Hughes as to whether Australia and New Zealand were presenting an ultimatum to the conference. Hughes, who was deaf, and especially so when it suited him, fiddled with his hearing aid, and asked for the question to be repeated. When it was, he replied: “That’s about the size of it, Mr President. That puts it very well.” When Wilson asked Hughes whether he expected the five million Australians he represented to be set against the twelve hundred million represented by the conference, Hughes responded, “I represent sixty thousand dead.” Finally, when the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George tried to mediate by asking Hughes if Australia would grant free access for missionaries in any New Guinea mandate, Hughes replied: “I understand that these poor people are very short of food and for some time past they have not had enough missionaries.” Wilson did not see the joke.

Yet if Hughes delighted the press and cartoonists with his tweaking of the president’s nose, in the end he had to compromise. The conference agreed that the League of Nations should create a three-tier system of mandates. Class C would allow the mandated territories to be part of the legal and economic systems of the power which had been granted the mandate. It was an ingenious solution, to which an Australian lawyer in the British delegation, John Latham, contributed. The custodial role of the League was preserved, and Class C territories were in effect demilitarised, since the nation receiving the mandate could not fortify them. Meanwhile, Australia could control the trade and immigration of the territory it administered.

White Australia

This arrangement allowed Hughes to preserve his core objectives of excluding Japanese commercial interests from New Guinea and maintaining the sanctity of White Australia, a policy to which he (like most Australians of that time) was passionately attached. Yet if Hughes gained German New Guinea, he had to accept that other former German colonies also became mandates administered by the states that occupied them in 1914 – and this meant that the Japanese, whom Hughes profoundly distrusted, kept control of the Caroline and Marshall Islands, which lie north of the equator.

German New Guinea, then, was a qualified victory for Hughes. So was another battle he fought bitterly in Paris: to stop the inclusion in the Covenant of the League of Nations a clause enshrining the principle of racial equality. Japan had been admitted to the inner circles of the allied powers by virtue of its being an ally in the war, and it now sought to secure a public statement to the effect that the peoples of any country could not be discriminated against because of their race or nationality. For Hughes, this proposed racial equality clause was anathema; it was, he thought, another insidious way for the Japanese to breach the walls of White Australia and penetrate the Australian economy.

Hughes was not alone in his reservations, but he became the very public face of opposition to the Japanese campaign. As he often did when thwarted, Hughes leaked to the press. His aim, in this case, was to stir up opposition to the racial equality clause in California, where there was as much support for racially discriminatory immigration as there was in Australia. This tactic seemed to work. The US president and his advisers became nervous about the possibility of the racial equality clause raising a storm of protest domestically. Opposition to the League of Nations was already growing in the United States because of its potential infringements of US domestic rights; this resistance would ultimately result in the US Senate’s refusing to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, a decision that was disastrous for the post-war security order. So far as the racial equality clause was concerned, it also meant that, after the Japanese had tried to get a watered-down statement included in the League preamble, they backed down.

Hughes felt vindicated. He had achieved his goal that “nothing shall go in, no matter how mild and inoffensive”. But his intransigence on the sensitive issue of racism, and the utter mortification he caused Japanese diplomats in Paris, damaged Australia’s reputation in Japan. The Japanese press attacked Hughes and demanded that Japan should turn its back on the League and create in Asia its own version of the Monroe doctrine, by which the United States asserted the right to monitor the actions of European states in the Americas. Even some of Hughes’s cabinet colleagues (whom, in typical style, he chose not to consult) thought that his offensive behaviour in Paris might have fuelled ultranationalism in Japan. Was he eroding rather than enhancing Australia’s security by strengthening the hands of those who wanted to keep Japan out of the League?

Indemnities

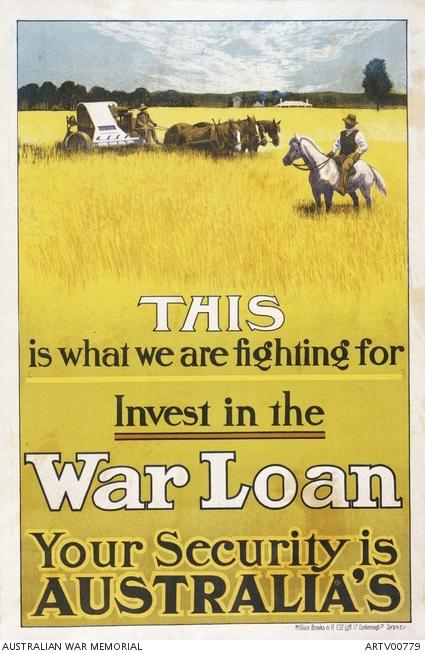

However ambiguous Hughes’s “success” on the racial equality clause might have been, his defeat in his most important battle at Paris was almost complete. This concerned indemnities from Germany. Hughes’s position was that Germany should be made to pay for all the costs of the war and postwar reconstruction. This was the only way, he thought, that Australia could discharge the significant war debt that it now owed to Britain, and also cover the cost of pensions and medical care for veterans. Like most belligerent countries, Australia had not funded its war effort by taxation (always politically sensitive) but by borrowings: from the British government and the Australian people through a series of “patriotic” war loans. The debt to London could not be written off because London, in turn, had funded its own war effort through borrowings from the United States. In the course of the summer of 1916, during the massive Somme offensive, for example, the private US bank J.P. Morgan had raised more than a billion dollars in America on behalf of the British government; this was no less than 45 per cent of British war spending in those months.

The question of inter-allied war debts and German reparations was a deeply divisive one, and at Paris it was finally agreed that the Germans should pay for more than actual physical damage to France and Belgium, as was originally suggested by the Americans. But Hughes’s battle to get Germany to pay the full costs of Australia’s war, and for pensions and other veterans’ benefits, was lost. The compromise that was finally hammered out was so unpalatable to Hughes that it was only in the interests of the unity of the British Empire that he finally signed the peace treaty.

The story of German reparations in the 1920s is a long and complex one. Suffice to say that by 1931, when reparations payments finally ended, Australia had received only £5.571 million against a total claim of £464 million – £364 million being for actual war expenditure, and £100 million for the capitalised value of pensions, repatriation and loss to civilian property. Moreover, what Australia had received was largely made up of ships seized in Australian ports and the value of expropriated property in New Guinea.

So Hughes returned to Australia deeply disappointed with the Treaty of Versailles. As he saw it, it was “not a good peace” for Australia but it was a good one for the United States. He said bitterly, “She who did not come into the war to make anything has made thousands of millions out of it. She gets the best ships. She has a good chance of beating us for world mercantile supremacy. She prevented us getting the cost of the war.”

In some ways Hughes’ disappointment was understandable. The quantifiable “spoils of war” for Australia were few and scarcely commensurate with the scale of the losses that Australia had suffered. No one would claim that a mandate to control German New Guinea was worth more than 60,000 dead. But Hughes’s expectations of the peace settlement were unrealistic. The rise of the United States, and the relative decline of the British Empire that Hughes so lamented, could not be reversed. The growth of American industrial might, which would make it a superpower in the twentieth century, was already in train before 1914. It was simply accelerated by the war.

For all his realist attitude to world politics, Hughes struggled to understand that this was not a matter of “injustice”. Long general wars tend to exhaust those who fight them, and they often leave the international balance of power fundamentally transformed. The First World War left Britain and its empire exhausted and in debt, while also shattering three of the dynastic monarchies that had dominated Europe for centuries. The world order which the Great Powers of Europe had gone to war to preserve was over by 1919, and the Treaty of Versailles, with all its flaws, was never going to restore it.

About the author

Joan Beaumont is Professor Emerita at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University. She is the author of Broken nation: Australians in the Great War and editor (with Allison Cadzow) of Serving our Country: Indigenous Australians, war, defence and citizenship.

About the article

A version of this article was published by the Melbourne Shrine of Remembrance in Remembrance, April 2019.

This article will appear in Issue 87 of Wartime, on sale from 10 July. View our Wartime page to purchase issues of the magazine.