The Simpson Prize 2023

The 2023 Simpson Prize Competition Question

How significant was Australia’s contribution to the Allied military victory on the Western Front in 1918?

Instructions

You are encouraged to debate, agree with, or challenge the question.

You are expected to use at least four sources listed below. Up to half of your response should use your own research.

Information about word or time limits, the closing date, entry forms, and judging can be found at the Simpson Prize official website.

The Simpson Prize is funded by the Australian Department of Education and run by the History Teachers’ Association of Australia.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people please be aware that this resource may contain images and names of deceased persons.

Source 1

Longstaff painted the work after attending the unveiling of the Menin Gate memorial, at Ypres in Belgium, on 24 July 1927. The memorial commemorated those men of the British Empire, including Australia, who died in the battles of the First World War and have no known grave.

Read more about Menin Gate at Midnight

Will Longstaff, Menin Gate at Midnight, oil on canvas, 137 x 270 cm. AWM ART09807.

Source 2

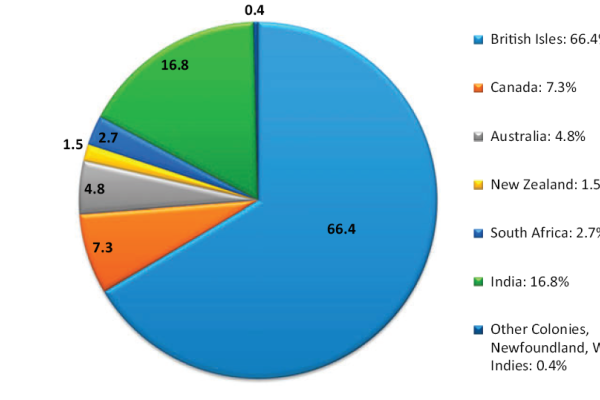

Statistics from Rhys Crawley's article ‘Marching to the Beat of an Imperial Drum: Contextualising Australia's Military Effort During the First World War’, Australian Historical Studies, 2015, p. 79.

Source 3

Extracts from Rhys Crawley’s article ‘Marching to the Beat of an Imperial Drum: Contextualising Australia's Military Effort During the First World War’, Australian Historical Studies, 46:1, 2015, pp. 64-80.

Read source 3

Extract A p. 66

Frustratingly, public discourse within Australia has not evolved in line with these developments in the international scholarly literature. Popular histories, with little basis in archival research or the wider literature, continue to flood the bookshelves with accounts that fail to place their battles within a broader context of who was fighting on Australia’s left and right. It is not uncommon for a reader of these accounts to be left with the impression that Australia did all the fighting. Moreover, the major Anzac Day ceremonies propagate this inaccuracy by failing to look beyond Australia’s contribution. In her 2013 speech at Townsville, in which the Prime Minister spoke of her gratitude for Australian service personnel, Julia Gillard, for instance, did not mention any other country. Similarly, Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s 2014 address in Canberra, which refreshingly spoke of the need to place Gallipoli within the broader context of operations on the Western Front, neglected to mention the important role performed by Australia’s allies. Abbott’s choice to not pay tribute to British forces in the presence of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge is less surprising than Foreign Minister Julie Bishop’s failure to mention France, the country in which she was speaking, beyond stating that Australian troops saved Villers-Bretonneux ‘in the defence of freedom’.

Extract B p. 80

To be sure, Australia’s military performed well and the AIF deserved its status as an elite formation: by 1918 Australian soldiers were both professional and adept at fighting and killing. Yet Australia’s military forces were never large enough to influence the outcome of the war by themselves, whether this be at Gallipoli, the Middle East, the Western Front, or on the world’s oceans. Nor did they want to. From the outbreak of the war Australia’s politicians and highest-ranking military officers realised that Australia was a very small player in a very large war. Reflecting the ideal of ‘Greater Britain’, the AIF and the RAN were both Australian and British, and knew that the strength of the imperial war effort was its combined weight, controlled and underpinned by Britain. It was this imperial force, with its many parts, acting in conjunction with its allies, that was ultimately victorious over Germany in 1918.

Source 4

The final chapter from Sir John Monash’s The Australian Victories in France, 1918, Hutchinson & Co, London, 1920. (This chapter is a detailed analysis of the significance of Australia’s role in the final battles of 1918 that led to Allied victory on the Western Front. Sir John Monash was the commander of Australian forces on the Western Front in 1918.)

CHAPTER XVII — RESULTS

The time has arrived when it is proper to take stock of gains and losses, and to endeavour to appraise, at its true value, the work done by the Australian Army Corps during its long-sustained effort of the last six months of its fighting career.

It has become customary to regard the actual captures of prisoners and guns as a true index of the degree of success which has attended any series of battle operations. Every soldier knows, however, that such a standard of judgment, applied alone, would render but scant justice. The actual captures in any engagement depend more upon the state of moral of the enemy and the temperament of the attacking troops than upon the military quality of the battle effort considered as a whole. While large captures necessarily imply great victories, it does not by any means follow that small captures imply the reverse.

Nevertheless, judged by such a purely arbitrary standard, the performances of the Australian Army Corps during the period under review are worthy of being set out in particular detail.

From March 27th, when Australian troops were for the first time interposed to arrest the German advance, until October 5th, when they were finally withdrawn from the line, the total captures made by them were:

|

Prisoners |

. . . . |

29,144 |

|

Guns |

. . . . |

338 |

No accurate record was ever kept of the capture of machine guns, trench mortars, searchlights, vehicles and travelling kitchens or pharmacies, nor of the quantity of Artillery ammunition, which alone must have amounted to millions of rounds.

During the advance, from August 8th to October 5th, the Australian Corps recaptured and released no less than 116 towns and villages. Every one of these was defended more or less stoutly. This count of them does not include a very large number of minor hamlets, which were unnamed on the maps, nor farms, brick-fields, factories, sugar refineries, and similar isolated groups of buildings, every one of which had been fortified and converted by the enemy into a stronghold of resistance.

Although the amount of territory reoccupied, taken by itself, is ordinarily no criterion of value, the whole circumstances of the relentless advance of the Australian Corps make it a convenient standard of comparison. The total area of all the ground fought over, from the occupation of which the enemy was ejected, amounted in the period under consideration to 394 square miles.

A much more definite and crucial basis for evaluating the military successes of the Corps is the number of enemy Divisions actually engaged and defeated in the course of the operations. Very accurate records of these have been kept, and every one of them was identified by a substantial contribution to the list of prisoners taken. An analysis of this investigation produced the following results:

The total number of separate enemy divisions engaged was thirty-nine. Of these, twenty were engaged once only, twelve were engaged twice, six three times, and one four times. Each time “engaged” represents a separate and distinct period of line duty for the enemy Division referred to.

Up to the time of the Armistice we had definitely ascertained that at least six of these thirty-nine enemy Divisions had been entirely disbanded as the result of the battering which they had received. Their numberings have already been given. It is more than probable that several other Divisions shared the same fate, by reason of the number of prisoners actually taken, and the other casualties known to have been inflicted. Up to the time when the signing of the Armistice precluded further inquiries, absolutely conclusive evidence of their disappearance had not been obtained.

In such an analysis it is possible to go even further, and to compare the tangible results achieved with the relative strength of the forces engaged. The Australian Army Corps of five Divisions represented 9½ per cent. of the whole of the remaining 53 Divisions of the British Army engaged on the Western Front. Its captures in prisoners, by the same comparison, and within the period reviewed—i.e., March 27th to October 5th—was 23 per cent., in guns 23½ per cent., and in territory reoccupied was 21½ per cent. of the whole of the rest of the British Army.

The ratio, therefore, of the results to the strengths, as between the five Australian Divisions and the whole of the rest of the British Army, was as follows:

|

Prisoners |

. . . . |

2.42 times. |

|

Territory |

. . . . |

2.24 ” |

|

Guns |

. . . . |

2.47 ” |

It is not, however, by the mere numerical results disclosed by such a comparison that the work of the Australian Army Corps should be judged. If a broad survey be made of the whole of the 1918 campaign, I think that the decisive part which the Corps took in it will emerge even more convincingly.

Such a survey will show that the whole sequence of events may be divided into five very definite and clearly-marked stages. The first was the arrest and bringing to naught of the great German spring offensive; the second was the conversion of the enemy’s offensive strategy into a distinct and unqualified defensive. Next followed the great, initial and irredeemable defeat of August 8th, which, according to the enemy’s own admissions, was the beginning of the end. Then came the denial to the enemy of the respite which he sought on the line of the Somme, which might well have helped him to recover himself for another year of war; and, finally, there was the overthrow of his great defensive system, on which he relied as a last bulwark to safeguard his hold upon French soil, a hold which would have enabled him to bargain for terms.

It must never be forgotten that whatever claims may be made to the contrary, Germany’s surrender was precipitated by reason of her military defeat in the field. Her submarine campaign, disappointing to her expectations as it had been, was still a potent weapon. Her fleet was yet intact. Our blockade was grievous, but she did in fact survive it, even though it continued in force for a full eight months after her surrender. The defection of Bulgaria and the collapse of Turkey might conceivably be a source of increased military strength, even if one of greater political weakness. Had she been able to hold us at bay in France and Belgium for but another month or six weeks, she could have been assured of a respite of three months of winter in which to organize a levy en masse. Who can say that the stress of another winter and the prospect of another year of war might not have destroyed the Entente combination against her?

On these grounds I believe that the real and immediate reason for the precipitate surrender of Germany on October 5th, 1918, was the defeat of her Army in the field. It followed so closely upon the breaching of the Hindenburg defences on September 29th to October 4th, that it cannot be dissociated from that event as a final determining cause.

Whether this view be correct or not, I think that the claim may fairly be made for the Australian Army Corps, that in each of the stages of the operations which led to this military overthrow, the Corps played an important, and in some of them a predominating, part. No better testimony for such a conclusion can be adduced than the admissions of Ludendorff himself.

Narrowing our survey of the closing events of the campaign to a consideration of the fighting activities of the Australian Corps, I would like to emphasize the remarkable character of that effort. Deprived of the advantage of a regular inflow of trained recruits, and relying practically entirely for any replenishments upon the return of its own sick and wounded, the Corps was able to maintain an uninterrupted fighting activity over a period of six months. For the last sixty days of this period the Corps maintained an unchecked advance of thirty-seven miles against the powerful and determined opposition of a still formidable enemy, who employed all the mechanical and scientific resources at his disposal.

Such a result alone, considered in the abstract and quite apart from any comparison with the performances of other forces, is a testimony, on the one hand, to the pre-eminent fighting qualities of the Australian soldier considered individually, and, on the other hand, to the collective capacity and efficiency of the military effort made by the Corps. I doubt whether there is any parallel for such a performance in the whole range of military history.

As regards the troops themselves, the outstanding feature of the campaign was their steadily rising moral. Always high, it was, in spite of fatigue and stress, never higher than in the closing days. A stage had been reached when they regarded their adversary no longer with cautious respect but with undisguised contempt.

On the part of the troops it was a remarkable feat of physical and mental endurance to face again and yet again the stress of battle. To the infantry a certain measure of periodical rest was accorded, but the Artillery and technical services had scarcely any respite at all. Almost every day of the whole period they worked and fought, night and day, under the fire of the enemy’s batteries, and under his drenching, suffocating gas attacks, for our battery positions were the favourite targets for his gas bombardments.

On the part of the staffs it was a period of ceaseless toil, both mental and physical. The perfection of the staff work, its precision, its completeness, its rapidity, its whole-souled devotion to the service of the troops, were the necessary conditions for the victories which were won.

Another outstanding feature was the uniformity of standard achieved by all the five Divisions, as well as the wonderful comradeship which they displayed towards each other. Omitting altogether the performances of any one of them in the previous years of the war, it is noteworthy that all so fully seized the opportunities that presented themselves, that each could boast of outstanding achievements during this period—the First Division for its capture of Lihons and the battles of Chuignes and Hargicourt, the Second Division for Mont St. Quentin and Montbrehain, the Third for Bray, Bouchavesnes and Bony, the Fourth for Hamel and Hargicourt, and the Fifth for Péronne and Bellicourt.

I must also pass in brief review the losses which the Corps suffered during its advance. From August 8th to October 5th the total battle casualties were as follows:

|

Killed |

. . . . |

3,566 |

|

Died of wounds |

. . . . |

1,432 |

|

Wounded |

. . . . |

16,166 |

|

Missing |

. . . . |

79 |

|

————— |

||

|

Total |

. . . . |

21,243 |

Averaging these losses over all five Divisions for the whole period, they amount to a wastage from all causes of seventy men per Division per day, which must be regarded as extraordinarily moderate, having regard to the strenuous nature of the fighting, the great results achieved, and the much higher rate of losses incurred by Australian troops during the previous years of the war. Even during periods of sedentary trench warfare the losses averaged forty per Division per day.

The total losses of the Army Corps during this period were, indeed, only a small fraction of Australia’s contribution to the casualty roll for the whole period of the war. It was the least costly period, for Australia, of all the fighting that her soldiers underwent. Had it been otherwise, the effort could not have been maintained for so long, nor could the spirit of the troops have been sustained. It was the low cost of victory after victory which spurred them on to still greater efforts.

Of the causes which contributed to so gratifying a result, much credit must be given to the great development in 1918 of mechanical aids, in the form of Tanks, and to a considerable augmentation of aeroplanes, Artillery and Lewis guns. Of all these the Corps proved eager to avail itself to the full.

But the main cause is, after all, the recognition of a principle of text-book simplicity, which is that a vigorous offensive is in the long run cheaper than a timorous defensive. No war can be decided by defensive tactics. The fundamental doctrine of the German conception of war was the pursuit of the unrelenting offensive; it was only when the Entente Armies, on their part, were able and willing themselves to put such a doctrine into practice that our formidable enemies were overcome.

It may be that hereafter I may be charged with responsibility for so relentlessly and for so long committing the troops of the Corps to a sustained aggressive policy. Such criticisms have already been whispered in some quarters. But I am sure that they will not be shared by any of the men whom it was my privilege to command. They knew that an offensive policy was the cheapest policy, and the proof that they accepted it as the right one was their ever-rising moral as the campaign developed.

“Feed your troops on victory”, is a maxim which does not appear in any text-book, but it is nevertheless true. The aim and end of all the efforts and of all the heavy sacrifices of the Australian nation was victory in the field. Nothing that could be done could lead more swiftly and more directly to its fulfilment than an energetic offensive policy. The troops themselves recognized this. They learned to believe, because of success heaped upon success, that they were invincible. They were right, and I believe that I was right in shaping a course which would give them the opportunity of proving it.

There are some aspects of the Australian campaign to which, before closing this memoir, I should like to make brief reference. Success depended first and foremost upon the military proficiency of the Australian private soldier and his glorious spirit of heroism. I do not propose to attempt here an exhaustive analysis of the causes which led to the making of him. The democratic institutions under which he was reared, the advanced system of education by which he was trained—teaching him to think for himself and to apply what he had been taught to practical ends—the instinct of sport and adventure which is his national heritage, his pride in his young country, and the opportunity which came to him of creating a great national tradition, were all factors which made him what he was.

Physically the Australian Army was composed of the flower of the youth of the continent. A volunteer army—the only purely volunteer army that fought in the Great War—it was composed of men carefully selected according to a high physical standard, from which, happily, no departure was made, even although recruiting began to fall off in the last year of the war, and there were some who had proposed a more lenient recruiting examination. The cost to Australia of delivering each fighting man, fully trained, to the battle front was too great to permit of any doubt whether the physical quality of the raw material would survive the wear and tear of war.

Mentally, the Australian soldier was well endowed. In him there was a curious blend of a capacity for independent judgment with a readiness to submit to self-effacement in a common cause. He had a personal dignity all his own. He had the political sense highly developed, and was always a keen critic of the way in which his battalion or battery was “run”, and of the policies which guided his destinies from day to day.

His intellectual gifts and his “handiness” made him an apt pupil. It was always a delight to see the avidity with which he mastered the technique of the weapons which were placed in his hands. Machine guns, Lewis guns, Mills’ bombs, Stokes’ mortars, rifle grenades, flares, fuses, detonators, Very lights, signal rockets, German machine guns, German stick bombs, never for long remained a mystery to him.

At all schools and classes he proved a diligent scholar, and astonished his instructors by the speed with which he absorbed and bettered his instruction. Conservatism in military methods was no part of his creed. He was always mentally alert to adopt new ideas and often to invent them.

His adaptability spared him much hardship. He knew how to make himself comfortable. To light a fire and cook his food was a natural instinct. A sheet of corrugated iron, a batten or two, and a few strands of wire were enough to enable him to fabricate a home in which he could live at ease.

Psychologically, he was easy to lead but difficult to drive. His imagination was readily fired. War was to him a game, and he played for his side with enthusiasm. His bravery was founded upon his sense of duty to his unit, comradeship to his fellows, emulation to uphold his traditions, and a combative spirit to avenge his hardships and sufferings upon the enemy.

Taking him all in all, the Australian soldier was, when once understood, not difficult to handle. But he required a sympathetic handling, which appealed to his intelligence and satisfied his instinct for a “square deal”.

Very much and very stupid comment has been made upon the discipline of the Australian soldier. That was because the very conception and purpose of discipline have been misunderstood. It is, after all, only a means to an end, and that end is the power to secure co-ordinated action among a large number of individuals for the achievement of a definite purpose. It does not mean lip service, nor obsequious homage to superiors, nor servile observance of forms and customs, nor a suppression of individuality.

Such may have been the outward manifestations of discipline in times gone by. If they achieved the end in view, it must have been because the individual soldier had acquired in those days no capacity to act intelligently and because he could be considered only in the mass. But modern war makes high demands upon the intelligence of the private soldier and upon his individual initiative. Any method of training which tends to suppress that individuality will tend to reduce his efficiency and value. The proverbial “iron discipline” of the Prussian military ideal ultimately broke down completely under the test of a great war.

In the Australian Forces no strong insistence was ever made upon the mere outward forms of discipline. The soldier was taught that personal cleanliness was necessary to ensure his health and well-being, that a soldierly bearing meant a moral and physical uplift which would help him to rise superior to his squalid environment, that punctuality meant economy of effort, that unquestioning obedience was the only road to successful collective action. He acquired these military qualities because his intelligence taught him that the reasons given him were true ones.

In short, the Australian Army is a proof that individualism is the best and not the worst foundation upon which to build up collective discipline. The Australian is accustomed to team-work. He learns it in the sporting field, in his industrial organizations, and in his political activities. The team-work which he developed in the war was of the highest order of efficiency. Each man understood his part and understood also that the part which others had to play depended upon the proper performance of his own.

The gunner knew that the success of the infantry depended upon his own punctilious performance of his task, its accuracy, its punctuality, its conscientious thoroughness. The runner knew what depended upon the rapid delivery at the right destination of the message which he carried. The mule driver knew that the load of ammunition entrusted to him must be delivered, at any sacrifice, to its destined battery; the infantryman knew that he must be at his tape line at the appointed moment, and that he must not overrun his allotted objective.

The truest test of battle discipline was the confidence which every leader in the field always felt that he could rely upon every man to perform the duty which had been prescribed for him, as long as breath lasted, and that he would perform it faithfully even when there was no possibility of any supervision.

Thus the sense of duty was always very high, and so also was the instinct of comradeship. A soldier, a platoon, a whole battalion would sooner sacrifice themselves than “let down” a comrade or another unit. There was no finer example of individual self-sacrifice, for the benefit of comrades, than the Stretcher-bearer service, which suffered exceedingly in its noble work of succouring the wounded, and exposed itself unflinchingly to every danger.

The relations between the officers and men of the Australian Army were also of a nature which is deserving of notice. From almost the earliest days of the war violence was done to a deep rooted tradition of the British Army, which discouraged any promotion from the ranks, and stringently forbade, in cases where it was given, promotion in the same unit. It was rare to recognize the distinguished service of a ranker; it was impossible for him to secure a commission in his own regiment.

The Australian Imperial Force changed all that. Those privates, corporals and sergeants who displayed, under battle conditions, a notable capacity for leadership were earmarked for preferment. If their standard of education was good, they received commissions as soon as there were vacancies to fill; if not, they were sent to Oxford or Cambridge to be given an opportunity of improving both their general and their special military knowledge.

As a general rule, they came back as commissioned officers to the very unit in which they had enlisted or served. They afforded to all its men a tangible and visible proof of the recognition of merit and capacity, and their example was always a powerful stimulus to all their former comrades.

There was thus no officer caste, no social distinction in the whole force. In not a few instances, men of humble origin and belonging to the artisan class rose, during the war, from privates to the command of Battalions. The efficiency of the force suffered in no way in consequence. On the contrary, the whole Australian Army became automatically graded into leaders and followers according to the individual merits of every man, and there grew a wonderful understanding between them.

The duties and responsibilities of the officers were always put upon a high plane. They had, during all military service with troops, to dress like the men, to live among them in the trenches, to share their hardships and privations, and to be responsible for their welfare. No officer dared to look after his own comfort until every man or horse or mule had been fed and quartered, as well as the circumstances of the moment permitted. The battle prowess of the Australian regimental officer and the magnificent example he set have become household words.

Then there must be a word of recognition of the work of the devoted and able Staffs. It was upon them, after all, that the principal burden of the campaign rested. Upon them, their skill and industry, depended the adequacy of all supplies and their proper distribution, the precision of all arrangements for battle, the accuracy of all maps, orders and instructions, the clearness of messages and reports, the completeness of the information on which the Commander must base his decisions, and the correct calculations of time and space for the movement of troops, guns and transport. Their watchword was “efficiency”.

“The Staff Officer is the servant of the troops.” This was the ritual pronounced at the initiation of every Staff Officer. It was a doctrine which contributed powerfully to the success of the staff work as a whole. It meant that the Staff Officer’s duties extended far beyond the mere transmission of orders. It became his business to see that they were understood, and rightly acted upon, and to assist in removing every kind of difficulty in their due execution. The importance of accurate and reliable staff work can be understood when it is realized that no mistake can happen without ultimately imposing an added stress upon the most subordinate and most helpless of all the components of an Army—the private soldier. An error in a clock time, the miscarriage of a message, the neglect to issue an instruction, a misreading of an order, an omission from a list of names, a mistake in a computation, an incomplete inventory, are bound in the long run to involve an added burden somewhere upon some private soldier.

The Staff of the Australian Army Corps, its Divisions and Brigades, consisted during the last six months almost entirely of Australians, many of them belonging to the permanent military forces of the Commonwealth, but more still men who, before the war, followed civilian occupations. Among both categories the quality of the staff work steadily grew in efficiency, speed and accuracy, and during the last period of active fighting it reached a very high standard indeed.

Had it been otherwise, I could not have carried out either the rapid preparations for several of the greater battles, or the frequent and complex interchanges of Divisions which alone rendered it possible for me to keep up a continuous pressure on the enemy, or the readjustments throughout the whole of the very large area always under my jurisdiction which became necessary as the advance proceeded.

No reference to the staff work of the Australian Corps during the period of my command would be complete without a tribute to the work and personality of Brigadier-General T.A. Blamey, my Chief of Staff. He possessed a mind cultured far above the average, widely informed, alert and prehensile. He had an infinite capacity for taking pains. A Staff College graduate, but not on that account a pedant, he was thoroughly versed in the technique of staff work, and in the minutiæ of all procedure.

He served me with an exemplary loyalty, for which I owe him a debt of gratitude which cannot be repaid. Our temperaments adapted themselves to each other in a manner which was ideal. He had an extraordinary faculty of self-effacement, posing always and conscientiously as the instrument to give effect to my policies and decisions. Really helpful whenever his advice was invited, he never obtruded his own opinions, although I knew that he did not always agree with me.

Some day the orders which he drafted for the long series of history-making military operations upon which we collaborated will become a model for Staff Colleges and Schools for military instruction. They were accurate, lucid in language, perfect in detail, and always an exact interpretation of my intention. It was seldom that I thought that my orders or instructions could have been better expressed, and no Commander could have been more exacting than I was in the matter of the use of clear language to express thought.

Blamey was a man of inexhaustible industry, and accepted every task with placid readiness. Nothing was ever too much trouble. He worked late and early, and set a high standard for the remainder of the large Corps Staff of which he was the head. The personal support which he accorded to me was of a nature of which I could always feel the real substance. I was able to lean on him in times of trouble, stress and difficulty, to a degree which was an inexpressible comfort to me.

To the Commanders of the Five Divisions I have already made detailed allusion. They were all renowned leaders. To all the Brigadiers of Infantry and Artillery and to the Heads of the Administrative Services who laboured under them, the limitations of space forbid my making any individual reference. But they were all of them men to whose splendid services Australia owes a deep debt of gratitude. In their hands the honour of Australia’s fighting men and the prestige of her arms were in safe keeping.

None but men of character and self-devotion could have carried the burden which they had to bear during the last six months of the war. In spite of stress and difficulty, unremitting toil and wasted effort, weary days and sleepless nights, fresh task piling upon the task but just begun, labouring even harder during periods of so-called rest than when their troops were actually in the line, this gallant band of leaders remained steadfast of purpose, never faltered, never lost their faith in final victory, never failed to impress their optimism and their unflinching fighting spirit upon the men whom they commanded.

It may be appropriate to end this memoir on a personal note. I have permitted myself a tone of eulogy for the triumphant achievements of the Australian Army Corps in 1918, which I have endeavoured faithfully to portray. Let it not be assumed on that account that the humble part which it fell to my lot to perform afforded me any satisfaction or prompted any enthusiasm for war. Quite the contrary.

From the far-off days of 1914, when the call first came, until the last shot was fired, every day was filled with loathing, horror, and distress. I deplored all the time the loss of precious life and the waste of human effort. Nothing could have been more repugnant to me than the realization of the dreadful inefficiency and the misspent energy of war. Yet it had to be, and the thought always uppermost was the earnest prayer that Australia might for ever be spared such a horror on her own soil.

There is, in my belief, only one way to realize such a prayer. The nation that wishes to defend its land and its honour must spare no effort, refuse no sacrifice to make itself so formidable that no enemy will dare to assail it. A League of Nations may be an instrument for the preservation of peace, but an efficient Army is a far more potent one.

The essential components of such an Army are a qualified Staff, an adequate equipment and a trained soldiery. I state them in what I believe to be their order of importance, and my belief is based upon the lessons which this war has taught me. In that way alone can Australia secure the sanctity of her territory and the preservation of her independent liberties.

Such a creed is not militarism, but is of the very essence of national self-preservation. For long years before the war it was the creed of a small handful of men in Australia, who braved the indifference and even the ridicule of public opinion in order to try to qualify themselves for the test when it should come. Four dreadful years of war have served to convince me of the truth of that creed, and to confirm me in the belief that the men of the coming generation, if they love their country, must take up the burden which these men have had to bear.

Source 5

Extract from Joan Beaumont, Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2013, pp. 517-518.

Australia’s contribution to victory

How much did Australia contribute to the victory that brought such mixed emotions? It is difficult to judge conclusively. In Australian popular history, it is often implied that the AIF played a central role in the Allied victory, particularly in March-April and August 1918, when the German offensive was stalled and the Battle of Amiens launched so successfully. Over the decades, it has also been widely claimed that the AIF was an exceptionally competent fighting force. As Bean said in 1938, ‘it has been referred to by at least some competent authorities in Germany, England, and America as being - at any rate towards the end of the War - the most effective of all the forces on the side of the Allies’. There were also many occasions during the war-only some of which have been cited in this book-on which the performance and courage of Australians in battle attracted the praise, even awe, of their contemporaries. The tactical skill of the AIF was also affirmed by later military historians. For example, Allan Millett and Williamson Murray’s 1988 study of military effectiveness in World War I concluded that the tactical innovations, which required small-group initiative and cohesion and a less hierarchical relation ship between officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers, worked best among elite troops, or in ‘forces whose social backgrounds did not cramp individualism [like the formidable Australian Corps]’.

There is therefore little doubt that the AIF was a well-trained and highly effective fighting body by the end of the war. However, the case for Australian exceptionalism has to be qualified. As the war progressed, other armies also embraced tactical innovation and-like the Canadians at Vimy Ridge and the German stormtroopers in March 1918 - achieved dramatic success as a result. Moreover, it is difficult to find valid measures to prove any one army’s superiority over another. The data that Australian historians sometimes cite as evidence of the AIF’s achievements - the numbers of tanks, prisoners or territory that Australian units captured as a proportion of totals taken by the British Expeditionary Force in a particular battle, for example-are not robust. They fail to take into account the many variables involved, including the nature of the terrain, the strength of enemy units, the complexity of defences and even the weather in different sectors of the battlefield.

Beyond that, it must be recognised that the AIF, however effective it was tactically, was largely an infantry force. The reality of World War I, proved time and time again on the Western and Eastern Fronts and in Palestine, was that artillery was the essential precondition of success by the infantry. In the imperial armies of which the AIF was a part, this artillery was largely provided by the British. So too was much of the technological innovation that led to improvements in artillery accuracy and the logistical support on which the AIF depended. Likewise, when the new integrated weapons systems that made such a contribution to the breaking the Western Front stalemate were developed in 1917-18, the aircraft and tanks that formed their key elements were again provided by the British.

Hence Australia’s role in World War I must be seen as a small part of a much larger British imperial effort. This in turn was part of a massive multinational war. Victory for the Allies came after years of exhausting slogging matches on multiple fronts in which the French, the ‘British’, the Russians, the Serbs and the late-arriving Americans all played a role. Perhaps a quarter of German deaths occurred on the Eastern Front. Victory also depended on many things other than land battles, critical though these were: the neutralising of the German U-boat campaign; the containment of the German High Seas Fleet; the achievement of Allied air superiority in multiple battle zones; and, underpinning everything, the mass production of munitions and armaments. To all this Australia, with its small economy, navy and air force, made little contribution. Even the value of the raw materials that it could contribute to the imperial war effort was diminished by the lack of shipping to transport them to Europe. To single out any one army, or indeed any one of these multiple variables, as the factor that ‘won’ World War I is to ignore the immense complexity and scale on which this war was fought.

Source 6

Extract written by German historian Gerd Krumeich. Translated from the German Historical Museum’s 2014 publication Der Erste Welt Krieg: In 100 Objekten (The First World War: In 100 objects), Stiftung Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin, 2014, p. 18.

The End of the War

….the combat readiness of the German soldiers also decreased. All the more so since from the spring of 1918 they were confronted with a very well-equipped American army that was already 1.5 million strong by July. In addition, the French deployed their more than 3,000 tanks so skilfully that the German soldiers lost what had remained of their courage. This is how 8 August 1918 came to be the ‘black day of the German army’ (Erich Ludendorff), when the Germans reported 30,000 ‘missing’ in one day when the Allied troops broke through near Amiens, and at the same time the Allies reported 30,000 German prisoners had been taken. From now on the German commanders could only focus on ending the war, although the propaganda continued to promise victory.

Source 7

Extract from C.E.W. Bean, The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol. V The A.I.F. in France: December 1917-May 1918, Angus and Robertson Ltd, Sydney, 1941, p. 177.

27th Mar., 1918 BEFORE AMIENS

One of the Australian war correspondents notes:

The units all tell one that the French people received them with open arms—sometimes with tears… “Les Australiens and les Ecossais sont de tres bons soldats” an old Frenchman said to-day to Cutlack, who had a ride in his cart.

So on March 27th on the road to Franvillers and Heilly the 3rd Division was met with demonstrations of welcome and affection. Women, who during the past night had seen the flashes of the enemy’s guns, like summer lightning on the horizon, coming closer to their homes, and for the first time had heard the swish and crash of enemy shells, now in a revulsion of pent-up feeling burst into tears and raised a thin cry of “Vive l’ A ustralie!” An old parish priest raised his hands and blessed the passing men. Some who had left their homes turned back, and others, who had not left, stayed on. ‘Fini retreat, Madame,” said one of the “diggers” gruffly, when the leading battalion was halted, and sat cleaning its rifles along the side of the Heilly street. “Fini retreat—beaucoup Australiens ici.”

Source 8

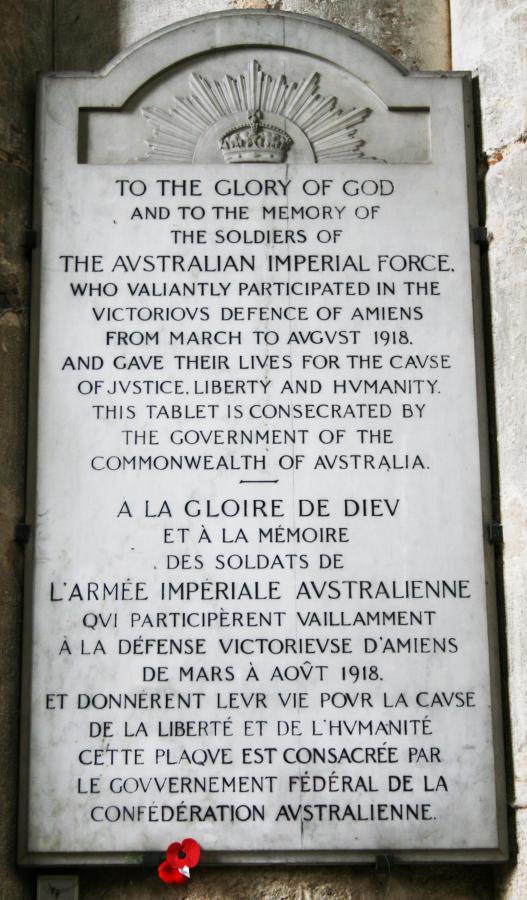

Memorial Plaque, Amiens Cathedral, France, erected 1920

Memorial plaque, Amiens Cathedral, France

Source 9

Map showing opposing armies on the Western Front in November 1918