Indonesian Confrontation (Konfrontasi) 1962–66

Background

“It is often said that soldiers are called in when politicians and diplomats have failed, but in this case the conflicts were fought by politicians, diplomats, and soldiers simultaneously.”

Peter Edwards, “Confrontation: Australia’s curious war of diplomacy” Wartime 5, Summer 1999, p. 44.

In 1961 Malayan and British officials proposed the creation of a federated state that would include the Federation of Malaya, Brunei, Singapore, and the British colonies of North Borneo and Sarawak. While Britain was granting independence to its south–east Asian colonies, it preferred them to align with the pro-British Malayan government(1) rather than Indonesia, which it feared would become communist-aligned and a threat to western interests.

Map showing the island of Borneo in 1962.

Map courtesy of the National Army Museum

Sukarno, the first President of Indonesia following independence, did not support the formation of Malaysia, which he believed was part of British attempts to maintain control in the area.(2) Sukarno was particularly opposed to the inclusion of the British territories on Borneo, as most of Borneo was under Indonesian rule. The Philippines, who felt they were the rightful rulers of North Borneo, were also opposed to the creation of Malaysia.

Sukarno, future President of Indonesia, with Australian Consul-General Charles Eaton, Indonesia, 1947. (Indonesian Press Photo Service, AWM P03531.001)

In January 1963, Indonesia declared a policy of Konfrontasi, destabilising the proposed Malaysian federation with the aim of breaking it up by engaging in economic, political, and military action without directly declaring war.

Britain, Australia and New Zealand already had military personnel in the area from the Malayan Emergency. They remained in place as Confrontation escalated, while the British increased their troop numbers. When Indonesian forces launched raids across Borneo in early 1963, the Australian Government found itself in a difficult position. Australia wanted Malaysia to be formed without open opposition from Indonesia.(3) It also faced pressure to assist the British, and was mindful of its relationship with the United States. While the United States was supportive of the creation of Malaysia, it was concerned that military intervention against Indonesia could lead to it aligning with communist powers.

When the US threatened to withdraw aid from Indonesia in an attempt to end fighting, Sukarno told the Americans to “go to hell”(4) and committed further troops to the conflict. The Australian Government needed to employ delicate diplomacy as it acted as peacemaker between Malayan, Indonesian, and Filipino leaders in the lead up to 16 September 1963 when the Federation of Malaya, Sarawak, Singapore, and North Borneo joined to become the Federation of Malaysia (Brunei declined to join; Singapore became independent in 1965).

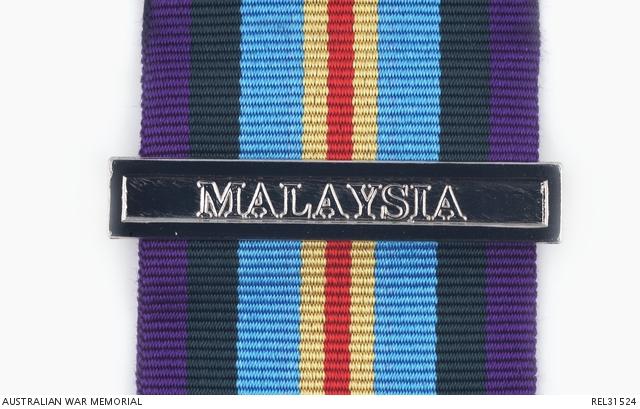

Australian Active Service Medal 1945 – 1975 with Malaysia clasp. (AWM REL31524)

Following the announcement of the creation of Malaysia, mobs in Jakarta attacked the Malayan Embassy and burnt down the British Embassy. Indonesia had recognised that Australia’s policy was different from that of the British and the United States, which went some way to explaining why the Australian Embassy was untouched.

In 1964, Australia joined other Commonwealth forces to protect Malaysia’s independence.

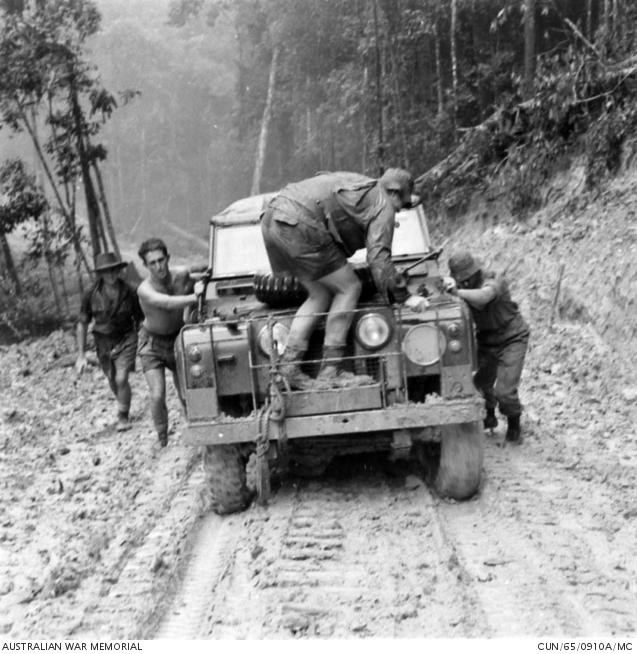

All three services of the Australian Defence Force joined other Commonwealth forces to protect Malaysia’s independence, providing materials and training, while constructing airstrips, roads, and bridges. To appease Britain and the United States, the Australian Government adopted a policy of “graduated response”,(5) providing the minimum forces necessary to meet the Indonesian threat. It was not expected that the armed services would have direct contact with the Indonesians.

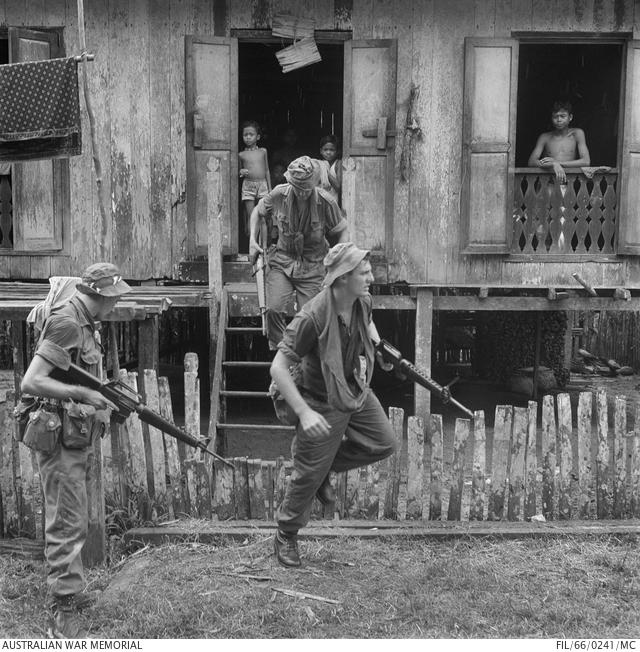

However, when Indonesian forces landed on the Malayan peninsula and the Indonesian military presence expanded in Borneo, combat was inevitable. The Australian Government eventually approved that military forces move from defending borders to engaging in more aggressive cross-border action. Australia and New Zealand troops took part in patrols and raids to destabilise Indonesian forces and protect the Malaysian border. There was a ban on the media knowing anything about cross-border raids, which were not made public until 1996.

Members from the 4th Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment carrying out patrols along the Malaysian-Indonesian border, Borneo, 1966. (AWM FIL/66/0241/MC)

In 1966, President Sukarno was removed from power by a military coup. Indonesia and Malaysia were then able to negotiate an end to the confrontation, signing a peace treaty.

Of the 114 Commonwealth soldiers who lost their lives as a result of Confrontation, 22 were Australian. While some were killed in action, other causes of death include drownings, motor vehicle accidents, illness, and injuries caused by a wild elephant. The role of the Australian Defence Force in south–east Asia continued after Confrontation, with an increasing commitment to the war in Vietnam.

24 Construction Squadron struggle to get a Land Rover up a muddy slope, North Borneo, 1965. (William Cunneen, AWM CUN/65/0910A/MC)

[1] Indonesian Confrontation, https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/indonesian-confrontation <accessed 24 October 2019>.

[2] Karl James, “Australia’s other Asian wars”, Wartime 41, January 2008, p. 14.

[3] Peter Edwards, “Confrontation: Australia’s curious war of diplomacy”, Wartime 5, January 1999, p. 46.

[4] https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/history/conflicts/australian-involvement-south-east-asian-conflicts/indonesian-confrontation-1963

[5] Peter Edwards, “Confrontation: Australia’s curious war of diplomacy”, Wartime 5, January 1999, p. 47.