The South African (Boer) War, 1899–1902

The South African War, or Boer War, broke out in October 1899 between the British Empire and the two Boer republics, the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (known to the British as the Transvaal). British mining interests sought access to the Transvaal’s rich diamond and gold mines, and the British government had earlier shown a desire to bring the republics under British sovereignty. The British had fought a war against the Transvaal in 1880–1881, but had been soundly defeated.

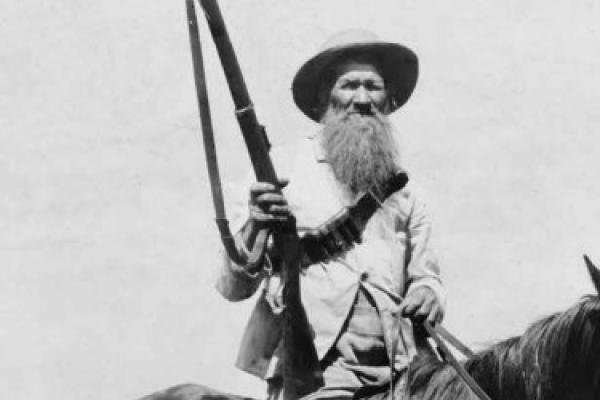

The South African War had three distinct phases. In the short first phase, mounted Boer forces invaded the British colonies of Natal and Cape Colony, and besieged the infantry-dominated British army in several places. A series of decisive battlefield defeats of British forces in mid-December 1899, known as “Black Week”, galvanised support for the war amongst British settlers in the colonies. The deployment of more British and colonial troops began the second phase of the war, with a British counter-offensive in early 1900 that captured the two Boer capitals, Bloemfontein and Pretoria, and most major towns in South Africa. During the third phase, from mid-1900 to the end of the war, Boer commandos conducted a guerrilla campaign against British forces and logistics. The British responded with a campaign of farm-burning, interning Boer civilians in concentration camps, and using mounted infantry columns in combination with a network of barbed wire and blockhouses to wear down the Boer will to fight. On 31 May 1902, the Boers surrendered and representatives of both sides signed the Treaty of Vereeniging.

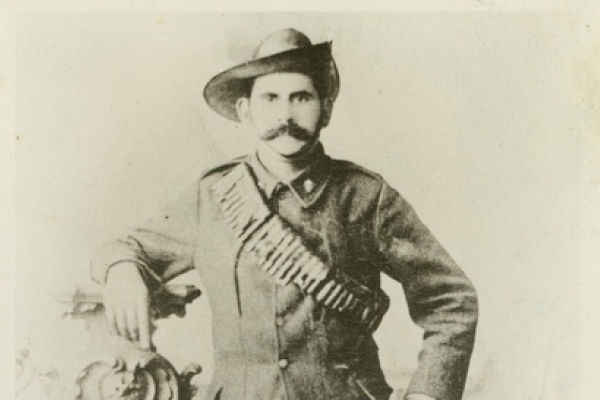

All six Australian colonies sent multiple contingents to the war, mainly mounted infantry. In 1902, the new Australian Federal government deployed battalions of the Australian Commonwealth Horse, the first time Australian (as distinct from colonial) soldiers had served overseas. Especially in the early parts of the war, more men volunteered for service than were needed. Although no formal racial restriction on military service existed, there seems to have been a general understanding among recruiters and policy makers that white colonials were preferred. This attitude was in tune with the emerging White Australia policy of the time, as well as the British understanding that the South African War was to be a “white man’s war”. Historians have since shown that this moniker was a misnomer, and black Africans served with British forces, and in some cases were pressed into service with Boer forces. All Australians who served in the colonial and Commonwealth contingents, including Aboriginal soldiers, volunteered for service and were assigned service numbers.

The Australian War Memorial acknowledges the research, support and generosity of Peter Bakker for his detailed research and dedication in the provision, discovery and identification in the names contained on this list.

Peter Bakker has been researching and documenting Aboriginal military involvement for over a decade. He has documented the service of Aboriginals in the South African War (Boer War) and in the AIF’s small War Graves Services unit at the end of World War One. Peter undertakes his research in close collaboration with family descendants and the Australian War Memorial to have the life and military service of these Indigenous men recognised through publications, photographic exhibitions and war memorials. He pioneered the establishment of Victoria's first Indigenous war memorial, located in Warrnambool.

The South African (Boer) War Service List

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people please be advised that the following site and pages contain the names, images and objects of deceased persons.

Finding Walter Parker

For years, Private Walter Parker’s story remained a mystery. Today, he is recognised as the first known Indigenous soldier to die while serving overseas.

Troopers, not trackers

Over the last few years it has become known that a number of Aboriginal men served in several Australian contingents during the Second Anglo-Boer War. However, there is a widely-circulated story of 50 “black trackers” that dominates the interpretation of the role that Aboriginal men played during the Boer War and the treatment they received at the end of their service.