Charles Bean

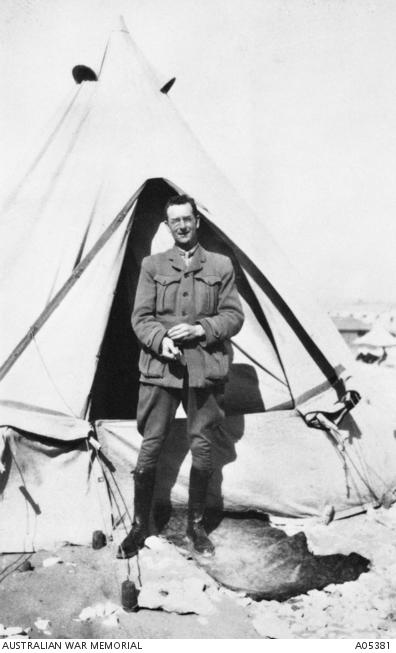

Charles Bean outside his tent in the AIF camp at Mena, Egypt, 1915.

In the early 1890s an English schoolteacher took his ten-year-old son to the museum room in the Hotel du Musée, near the battlefield of Waterloo. The boy was fascinated by the relics of the famous battle and dreamt of creating his own museum as he picked up what he imagined were relics of the fighting in the fields outside. The boy was Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean. His experience at Waterloo was a foretaste of the labours that would occupy most of his adult life: the establishment of the Australian War Memorial and the writing of the official history of Australia during the First World War.

Bean was born in Bathurst, New South Wales, on 18 November 1879, but his family moved to England ten years later. On the completion of his secondary education he won a scholarship to Hertford College, Oxford, where he studied classics and graduated with 2nd class honours. Bean returned to Australia in 1904, was admitted to the New South Wales Bar and for the next two years traveled on the legal circuit around the state. This experience led to The impressions of a new chum, a description of Australia through the eyes of someone returning after a long absence; the manuscript was not published, but material from it was printed as eight articles in the Sydney Morning Herald. They foreshadowed some of the themes that would recur in Bean's later work, particularly the idea that Australians represented the best of the British race and that the finest of them lived in the bush. With publication behind him, Bean decided to become a journalist, and he joined the Herald as a junior reporter in June 1908.

One of Bean's first assignments was as special correspondent on HMS Powerful, flagship of the of the Royal Navy squadron on the Australian station. Bean assembled his reports into The flagship of the south, a book which he published himself. Shortly afterwards he was sent to western New South Wales to do a series of articles on the wool industry. At first uninterested in the subject, Bean soon hit on the idea that the most important product of the wool industry was men on whose labour it depended, and he described their lives in sympathetic detail. Once again he put the articles into a book, On the wool track, published in 1910.

In mid-1914 Bean was given the task of writing a daily commentary on the gathering crisis in Europe. Although he could not have known it, he had begun writing about the conflict that would come to dominate his life. In September he won a ballot held by the Australian Journalists Association to become Australia's official war correspondent, narrowly defeating Keith Murdoch. Bean remained a civilian but held the honorary rank of captain. He travelled to Egypt with the first contingent of the AIF and landed at Gallipoli at 10 am on 25 April, a few hours after the dawn attack. Having annoyed some Australian troops in Egypt for reports in which he revealed that some men were being discharged and sent home for indiscipline, Bean won their admiration on Gallipoli. Two weeks after the landing he was recommended for a decoration for his bravery during the Australian charge at Krithia; as a civilian was ineligible for the award, so he was mentioned in dispatches instead. In August, Bean was shot in the leg but refused to leave the peninsula; remaining in his dug out he had his wound dressed daily until it was healed. He stayed on Gallipoli throughout the campaign, continually sending stories back to Australia and filling the first of the 226 notebooks he would amass by the end of the war.

Bean had noticed that Australian soldiers were devoted collectors of battlefield souvenirs and imagined that a museum featuring these objects might be created after the war. But it was not until he had witnessed the carnage on the Western Front in the second half of 1916 that he began to conceive a memorial that would not only house battle relics, but also commemorate those who had been killed. He had also become aware that the British and Canadians were planning to create their own war museums. In November 1916 Bean suggested to the Australian Minister for Defence, Senator Pearce, that photographs and relics of the fighting around Pozières should be put on display in a national museum. Pearce, whose motives were more narrowly political, was beginning to agree that a national institution could be useful, if only to mollify the state governments: they were demanding relics to commemorate the service of their own troops.

Bean (front row, right) as a war correspondent in France, 1916.

But it was not until 16 May 1917 that a unit known as the Australian War Records Section began operations under the command of Lieutenant J.L Treloar. In some respects the creation of this unit marks the birth of the Memorial.

Perhaps with the possibility of a detailed history in mind, Bean also urged the systematic collection of records. But it was not until 16 May 1917 that a unit known as the Australian War Records Section began operations under the command of Lieutenant J.L Treloar. In some respects the creation of this unit marks the birth of the Memorial. In September 1917 Bean outlined his thinking in the Commonwealth Gazette, describing war relics as "sacred things". Amid the horrors of the Western Front, Bean became more sensitive to the sacrifice of the troops, and as the number of dead increased his sense of obligation to the fallen became stronger.

The war's end brought Bean no respite. Shortly before the Armistice he wrote In your hands Australians, a short book in which he outlined his vision of the new Australia which could be created after the war. Early in 1919 he returned to Gallipoli as the head of the Australian Historical Mission to collect relics for the Memorial, obtain Turkish accounts of the campaign and report on the condition of war graves. The book in which he described the mission did not appear until 1948, when the official histories had been completed.

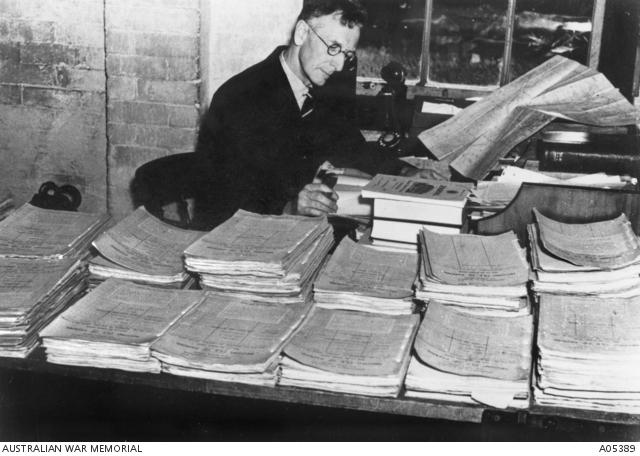

On his return to Australia in 1919 Bean and his staff moved into Tuggeranong homestead, south of Canberra, to work on the official history. When he began Bean imagined that the history would take five years to write; in the event it took 23 years, and the final volume did not appear until 1942. In 1946 Bean produced a single-volume history of the war, ANZAC to Amiens. Although it is unlikely that Bean's massive history of the war was widely read, sales were good and it was warmly acclaimed. In 1930 the Royal United Services Institution gave Bean an award for the first three volumes, and he received an honorary degree from the University of Melbourne in the same year. When the final volume of the official history was completed, the Prime Minister, John Curtin, congratulated Bean on his achievement.

Bean working on files during the writing the WW1 Official History.

Just before the final volume of the official history was published, Bean's second ambition came to fruition with the opening of the Australian War Memorial on 11 November 1941. By then the Second World War was in its third year. Having witnessed the fighting in the First World War, Bean had fervently hoped that there would never be another such conflict. He became an active member of the League of Nations Union in the early 1930s and, in the hope that it would preserve peace, had supported appeasement of Nazi Germany until it became obvious that war could not be avoided. During the Second World War Bean wrote a pamphlet called The old AIF and the New in 1940 and War aims of a plain Australian, a book in which he decried the failure of Australians to live up to the ideals which, he believed, had emerged at the end of the First World War. Bean also assisted the Department of Information by providing liaison between the Chiefs of Staff and the press, and in 1942 he became chairman of the new Commonwealth Archives Committee.

After the war Bean sought employment where he could. He was 66 when the Second World War ended, and the volumes he had produced generated no income. The only copyright he held was for ANZAC to Amiens, and it sold very slowly. In 1952 he became chairman of the Board of Management of the War Memorial (an unpaid position) and accepted a commission to examine First World War relics to determine what should be kept and what discarded. Between 1947 and 1958 he chaired the Promotion Appeals Board of the Australian Broadcasting Commission. In 1950 he wrote a history of Australia's non-government schools. Some of Bean's pre-First World War books, The dreadnought of the Darling and On the wool track, were republished in new editions. Towards the end of his life Bean planned to return to the subject that had occupied most of his adult life with a series of biographies but only one was written: Two men I knew, about Generals Bridges and Brudenell White, was his last book.

Often described as a modest man, it appears that Bean was also quite shy. He admitted that he was "too self conscious to mix well with the great mass of men", yet it was the great mass of men that he sought to commemorate in his work and whose respect he hoped to earn. His performance on Gallipoli cemented his reputation for bravery, and many of those with whom he worked closely, both during and after the war, held him in high regard. His long-time assistant, Arthur Bazley, described Bean as one of the finest men he had ever known, and Ken Inglis wrote that people who knew him admired and loved him.

In 1964, his health failing, Bean was admitted to Concord Repatriation Hospital and remained there until he died in August 1968. His official history of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 is his greatest monument, and the Memorial that he first imagined in the summer of 1916 has become a major repository of Australian military history, a museum and a memorial to the fallen. Included in its collection are the voluminous notebooks, letters and diaries that Bean started when he sailed from Australia with the First AIF in November 1914.

Note on sources and further reading

Dudley McCarthy, Gallipoli to the Somme: the story of C.E.W. Bean (Sydney, 1983).

Dennis Winter, Making the legend: the war writings of C.E.W. Bean (University of Queensland Press, 1992), contains annotated excerpts from Bean's notebooks, dispatches, diaries, letters and published histories, and the introduction contains biographical information.

Ken Inglis, C.E.W. Bean, Australian historian (University of Queensland Press, 1970), and Inglis's entry on Bean in the Australian dictionary of biography also provide useful information on Bean's life and work.

More recent books on Bean include Ross Coultharts, Charles Bean: If people really knew: One man's struggle to report the Great War and tell the truth, 2014.

Peter Rees, Bearing Witness: the remarkable life of Charles Bean, Australia's greatest war correspondent, 2015.

Also of note is Charles Bean: Man Myth Legacy A collection of papers delivered at the UNSW 2016 Canberra -hosted conference of the same name, NewSouth Books August 2017.

Charles Bean is one of eight “cosmopolitan conservationists” (Walter Burleigh Griffin is another) featured in the book Cosmopolitan Conservationists – Greening Modern Sydney by Dr Peggy James, 2013.

These books are available for viewing in the Memorial's Research Centre.

Hon Justice Geoff Lindsay has produced several papers about Bean.

Be Substantially Great In Thy Self: Getting to Know C.E.W. Bean; Barrister, Judge’s Associate, Moral Philosopher Geoff Lindsay S.C.

Having a Voice: CEW Bean as a Social Missionary. Geoff Lindsay S.C, 2017

The Forgotten CEW Bean.Geoff Lindsay S.C, 2016

At least two academic theses have been written about Bean. Richard Glenister, C.E.W. Bean, colonial historian: the writing of the history of the AIF in France during World War I (1983), describes the writing of the official history. Stephen Ellis' C.E.W. Bean, a study of his life and works (dated 1978 but apparently written in the late 1960s), discusses the influence of Bean's life and character on his writing. Both contain biographical information and describe his early writing.

More general works also contain information about Bean. Michael McKernan, Here is their spirit: a history of the Australian War Memorial 1917-1990 (University of Queensland Press and the Australian War Memorial, 1991), contains many references to Bean's role in establishing the Memorial.

Films about Bean include,“Charles Bean’s Great War ” Dramatised documentary. Wain Fimeri 2010

Bean's papers are held by the memorial and described in A guide to the personal, family and official papers of C.E.W. Bean, available in the Research Centre. The 12-volume official history has been reprinted several times, most recently, and with new introductions, by University of Queensland Press in the 1980s.