History of the Australian War Memorial

An aerial photograph of the Australian War Memorial, 1945.

Here is their spirit, in the heart of the land they loved; and here we guard the record which they themselves made.

Charles Bean, 1948

The Memorial ranks among the world's great national monuments. Sharply etched grandeur and dignity in its stylised Byzantine profile contrast with a distinctively Australian setting among lawns and eucalypts at the head of a wide ceremonial avenue, Anzac Parade. Kangaroos from nearby bushy hills occasionally add to the physical effect.

The Memorial is more than a monument. Inside the sandstone building, with its copper-clad dome, selections from a vast National Collection of war relics, official and private records, art, photographs, film, and sound are employed to relate the story of the Australian nation's experience in world wars, regional conflicts, and international peacekeeping.

The Memorial forms the core of the nation's tribute to the sacrifice and achievement of the more than 103,000 Australian men and women who died serving their country, and to all those who served overseas and at home. A central Commemorative Area flanked by arched cloisters houses the names of the fallen on the bronze panels of the Roll of Honour. At the head of the Pool of Reflection, beyond the Flame of Remembrance, stands the towering Hall of Memory, with its interior wall and high dome clad in a six-million-piece mosaic and illuminated by striking stained-glass windows. Inside lies the Tomb of the Unknown Australian Soldier, a symbolic national shrine.

Conception

Many a man lying out there at Pozières or in the low scrub at Gallipoli, with his poor tired senses barely working through the fever of his brain, has thought in his last moments: 'Well – well – it's over; but in Australia they will be proud of this.'

Charles Bean

After the Gallipoli campaign of 1915, the Australians of the 1st AIF (Australian Imperial Force) and their official war correspondent, Charles Bean, moved on to the major battle theatre of the Western Front in France and Belgium. The Australians' first big battles were at Fromelles and Pozières in July 1916. Bean was deeply moved by the sufferings of the men. He wrote in his diary:

"Pozières has been a terrible sight all day … One knew that the Brigades which went in last night were there today in that insatiable factory of ghastly wounds. The men were simply turned in there as into some ghastly giant mincing machine. They have to stay there while shell after huge shell descends with a shriek close beside them – each one an acute mental torture – each shrieking tearing crash bringing a promise to each man – instantaneous – I will tear you into ghastly wounds – I will rend your flesh and pulp an arm or a leg – fling you half a gaping quivering man (like these that you see smashed around you one by one) to lie there rotting and blackening like all the things you saw by the awful roadside, or in that sickening dusty crater. Ten or twenty times a minute every man in the trench has that instant fear thrust tight upon his shoulders – I don't care how brave he is – with a crash that is a physical pain and a strain to withstand."

It was at Pozières that Bean resolved these men and their ordeal should not be forgotten. A month later the idea of a memorial museum for Australian soldiers was born, as Bean's assistant and confidant Arthur Bazley later recalled:

"I remember in August 1916 when after his busy days tramping the Pozières battlefield and visiting units in the line he would roll out his blankets on the chalk firestep of the old British front line … on the edge of Becourt Wood and Sausage Gully. We used to sleep feet to head – C.E.W.B. (Bean), Padre Dexter, myself, and others – and although I cannot recall the actual conversations today I do remember that on a number of occasions he talked about what he had in his mind concerning some future Australian war memorial museum."

Troops of the 2nd Australian Division chatting during movement to the trenches in France, 1916.

Perhaps unbeknownst to Bean, the then Federal Member for Bendigo, Alfred John Hampson, had advocated for “a national monument after the fashion of the Arch of Victory….or like the Statue of Liberty at New York, which will stand for all time” in an exchange with Mr King O’Malley in Parliament on 11 November 1915, three years to the day before the Armistice was signed. Hampson wanted to “erect a memorial to last through the ages in recognition of the bravest of the Australians who have fought and died for their country” in the new national capital, Canberra.

It is not known if Bean, then the official war correspondent on Gallipoli, was aware of this exchange in the Federal Parliament. Local war memorials and monuments to earlier conflicts had been erected but nothing national had been envisaged publicly. It is also interesting to note that at the time of Hampson’s suggestion the ANZACs had not yet withdrawn from Gallipoli and the outcome of the war was far from clear.

The founding fathers

Two men, above all others, shaped the Memorial: Charles Bean, who became Australia's Official Historian of the First World War, and John Treloar, the Director of the Memorial between 1920 and 1952.

Charles Bean (1879–1968) was born in New South Wales but grew up and was educated largely in Britian. He returned to Australia and worked as a journalist, and in 1914 was chosen by the journalists' association as official war correspondent. Bean went ashore during the landing on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, and for the rest of the war followed the movements and battles of Australian soldiers. As well as conceiving and lobbying for the creation of the Australian War Memorial, he was appointed to oversee the production of the 12-volume Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 and he wrote six of the volumes, completing the last in 1942.

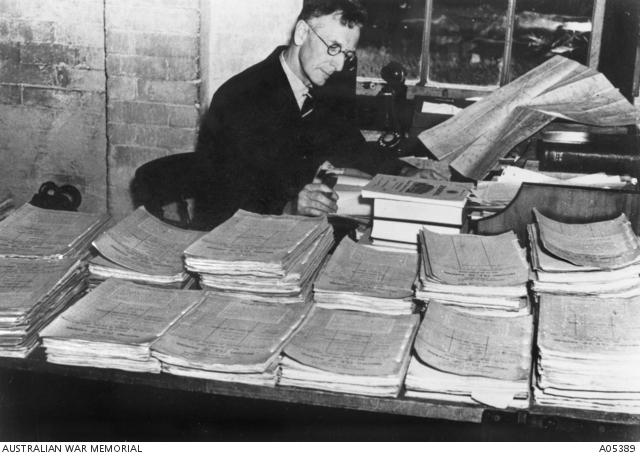

Bean working on the writing of the official history of the First World War, Victoria Barracks, Sydney, c.1935.

John Treloar (1894–1952) contributed more than any other person to the realisation of Bean's vision. Treloar, who came from Melbourne, also landed on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. In 1917, as a captain, he was appointed to head the newly created Australian War Records Section (AWRS) in London, responsible for collecting records and relics for the future museum and to help the official historian in his work. After the war Treloar devoted his life to the Memorial, and influenced almost every aspect of its development. Appointed Director of the Memorial in 1920, he remained in this position for the rest of his life, apart from a brief period in charge of the Military History and Information Section (MHIS) during the Second World War.

Lieutenant Colonel J.L. Treloar, 0Officer-in-Charge, Military History and Information Section (MHIS), Cairo, Egypt, c. 1941

Building the National Collection

The Australian War Records Section (AWRS) was set up in 1917 to ensure Australia would have its own collection of records and relics of the great war being fought. Treloar devoted himself especially to improving the quality of the unit and formation war diaries, which recorded operations and activities daily, and to ensuring that after the war the official historian would have a well-ordered collection of the diaries and supplementary primary source material to work from.

Others, such as Sid Gullett and Ernie Bailey, went out into the field to collect relics or material evidence of the conflict. At the same time orders were given to soldiers to do their bit in collecting for the projected museum and, in this way, some 25,000 relics were gathered.

Bean and Treloar also arranged for the appointment of official war artists and photographers. There were 18 official war artists, and among the best-known were Will Dyson, George Lambert, and Arthur Streeton. Bean's official photographers included two adventurers, Frank Hurley and Hubert Wilkins. Hurley had been to the Antarctic with both Mawson and Shackleton, while Wilkins had been to the Arctic and in 1912 had filmed the Balkan War with the Turkish Ottoman army. Bean insisted that art and photography should show the war as it was, not present an idealised version.

Melbourne and Sydney exhibitions

After the First World War it took a long time before the Memorial's building in Canberra was constructed. Initially there were delays in arousing public and government enthusiasm. Then the financial crash and the subsequent Great Depression intervened. In the meantime large, long-running exhibitions were held in Melbourne and Sydney. The Australian War Museum opened on Anzac Day 1922 in the Exhibition Building, Melbourne. This exhibition of war relics was enthusiastically received by press and public, and attracted large crowds. The exhibition closed in 1925 and was moved to Sydney, where it remained until 1935.

A permanent home

In 1918 Bean imagined how the Memorial would appear:

on some hill-top – still, beautiful, gleaming white and silent, a building of three parts, a centre and two wings. The centre will hold the great national relics of the AIF. One wing will be a gallery – holding the pictures that our artists painted and drew actually on the scene and amongst the events themselves. The other wing will be a library to contain the written official records of every unit.

The Memorial's design was a compromise between the desire for an impressive monument to the fallen and a budget of only £250,000. An architectural competition in 1927 failed to produce a satisfactory single design for the building. Two of the entrants in the competition, Sydney architects Emil Sodersteen and John Crust, were encouraged to submit a joint design, incorporating Sodersteen's vision for the building and Crust's concept of cloisters to house the Roll of Honour with its more than 60,000 names. The joint design was accepted and forms the basis of the building we see today, which was completed and opened to the public on Remembrance Day, 11 November, in 1941.

The postwar years

As Australia entered the Second World War the Memorial in Canberra was still not complete. It was intended to be devoted primarily to the First World War, but as it became apparent that the new war was of a comparable scale, it became inevitable that the scope of the Memorial should be extended. In 1941 the government extended the Memorial's charter to include the Second World War; in 1952 it was again extended to include all Australia's wars.

Guiding ideas

In keeping with the sombre, commemorative tone of the Memorial, Charles Bean was from the start concerned that it should not be seen to be glorifying war or triumphing over the enemy. He urged Treloar and others not to speak about "trophies", preferring the term "relics". He also urged that captions and text should not use derogatory terms for former enemies, such as "Hun" or "Abdul".

In the 1950s Bean drew up a list of exhibition principles, suggesting among other things that the galleries should "avoid glorification of war and boasting of victory" and "perpetuating enmity … for both moral and national reasons and because those who have fought in wars are generally strongest in their desire to prevent war". In general, he decided, former enemies should be treated as generously as were Australians. The exhibitions also needed to be made relevant and engaging, for example, by presenting relics as objects with their own story rather than as just examples of a type. Bean also thought of the future exhibits should be "so described and displayed as to be understood and interesting 75 years after the events".