Australian Artists

Daniel Boyd (born 1982)

Lives and works in Sydney, Australia

Daniel Boyd is a Kudjla/Gangalu man from Far North Queensland.

His work reinterprets European perspectives of Australian history using photographs, art-historical references, and his own personal and cultural history.

Before beginning his residency for the print portfolio, Boyd discovered a number of his relatives had served in the First World War, including his great grandfather William “Bert” Brown. Brown had enlisted from the

Barambah–Cherbourg Mission in July 1917 at the age of 18, and was sent to Egypt the following January to join the 11th Australian Light Horse Regiment. The regiment had over 30 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander members, more than any other unit in the Australian Imperial Force.

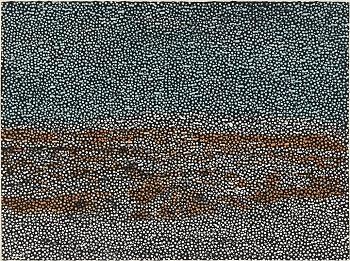

Through research at the Memorial Boyd also discovered the drawings of Otho Hewett, who had sketched many of the battlefields and places where the 11th Light Horse had served. In his print Boyd has re-appropriated one of Hewett’s panoramic drawings of Magdhaba to trace his own visual history back to his great-grandfather through landscape and place. Over Hewett’s image Boyd layered a black woodcut of dots altering how the work beneath is viewed. As the dots are reminiscent of the visual language and composition of Western Desert painting, Boyd provides a specifically Aboriginal response to the First World War.

Megan Cope (born 1982)

Lives and works in Melbourne, Australia

Megan Cope is from the Quandamooka region (Moreton Bay) in Queensland. Cope’s diverse practice engages with issues of identity, colonisation, the environment, and map-making.

Engaging with family stories of war for the first time, Cope began uncovering the histories of seven Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men from Stradbroke Island who served in the First World War. This print focuses on the service of Cope’s great-great uncle Private Richard Martin, who enlisted in December 1914.

In 1915 Martin joined the 15th Battalion in Gallipoli before being transferred to the 47th Battalion and sent to the Western Front. The 47th was involved in costly battles at Bullecourt, Messines, and Passchendaele, and Martin was wounded twice. On 28 March 1918 the German army launched a major offensive near the French village of Dernancourt. The 47th Battalion defended its position, and the German operation failed. However there were many casualties, and among the dead was Richard Martin.

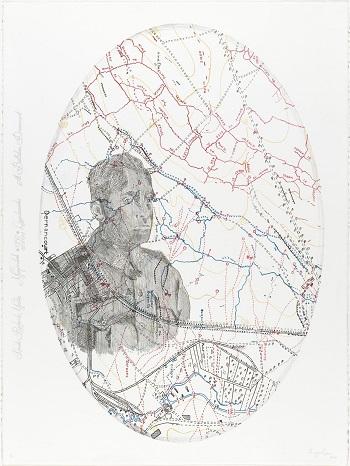

Cope’s portrait of Martin is printed over the delicately traced lines of a map relating to the battle of Dernancourt. Cope often works with military maps and was interested in the way armies assigned familiar names to foreign places, just as colonisers did for Aboriginal lands.

Helen Johnson (born 1979)

Lives and works in Melbourne, Australia

In her work Helen Johnson explores the ongoing formation of Australian identity and the relationship between personal and official histories.

In approaching her commission Johnson grappled with the idea of commemoration in a contemporary context, and the distance she felt from a war that was not part of her family’s lived experience. She began searching through the Australian War Memorial’s online archives for different images relating to the First World War, but felt uncomfortable focusing on a specific person or narrative. After weeks of looking at a broad range of material, she reflected on the search history in her web browser as a subjective path she had taken through this vast and complex subject. Employed as a framing device for her response to commemoration, it became the subject of her print. For Johnson, “any form of commemoration is a framing – engaging with a memory of an event or a set of memories”. She added that she was interested in the idea of the print “acknowledging itself as a frame”.

Johnson copied her search history into a document, manipulating it to create a literal frame within the four edges of the paper. The text is small and on the verge of being illegible, its content emerging only when studied closely. The interference ink in which it has been printed contains pearlescent pigments that shift between violet and green when viewed from different angles. Johnson saw this as a way of acknowledging that, from her perspective, there is no fixed statement being made in this work about what the First World War was, or means to us now, or how it should be viewed or commemorated.

Mike Parr (born 1945)

Lives and works in Sydney, Australia

Mike Parr, considered one of Australia’s most important and influential artists, works across diverse media platforms, including performance art, drawing, and printmaking. He has always been fascinated with the act of looking, how it challenges the viewer, and the distortion of memory over time. Parr’s creation of a double-sided print represents the division between public and private memory.

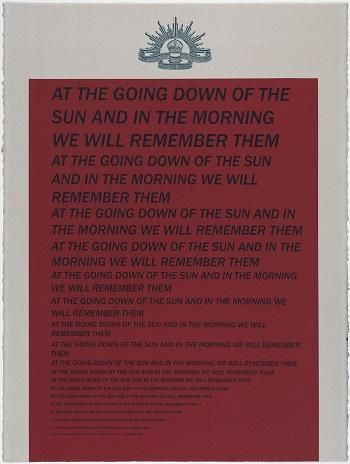

“At the going down of the sun and in the morning we will remember them” is a refrain from the Ode of Remembrance, and is repeated in decreasing fonts on the front side of the print so that the text narrows towards a vanishing point at the bottom. The artist uses the the diminishing text of the refrain as a melancholic device as well as a reflection on the passage of memory through generations.

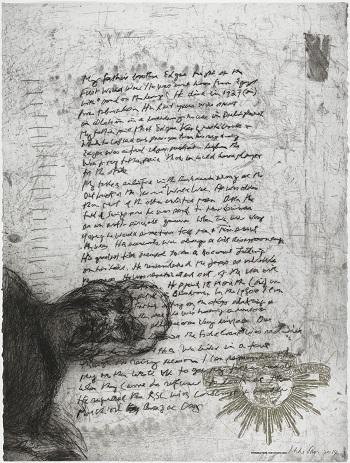

On the other side of the print the hand-etched text recounts the Parr family’s military history, specifically that of his uncle Edgar in the First World War and of his father in the Second World War. The two sides of the print combine to present remembrance as a constant shift between the public and the private, the formalised and the almost forgotten.

The text reads:

“My father’s brother Edgar fought in the First World War. He was sent home from Egypt with “sand on the lungs”. He died in 1927 from tuberculosis. His last years were spent in isolation in a boarding house in Darlinghurst. My father said Edgar kept notebooks in which he copied out passages from his reading. Edgar was a first class cricketer before the War and my father said he could have played for the State.

My father enlisted in the Australian army at the outbreak of the Second World War. He was older than most of the other enlisted men. After the fall of Singapore he was sent to New Guinea as an anti-aircraft gunner. When we were very young he would sometimes tell me and Tim about the War. His accounts were always a bit disappointing. His greatest fear seemed to be a coconut falling on his head. He remembered the Japs as invisible presences.

He was repatriated out of the War with a nervous condition. He spent 18 months in Greenslopes Hospital in Brisbane. In the 1950s I can remember my father sitting on the steps shaking and crying. My mother said he was having a nervous breakdown. We all became very anxious. Our small farm behind the Gold Coast was reclaimed by the bank in 1960. We lived in a tent through the rainy season. I can remember that my mother wrote off to get my father’s medals. When they came he refused to look at them. He regarded the RSL with contempt and wouldn’t march on Anzac Day.”

Sangeeta Sandrasegar (born 1977)

Lives and works in Melbourne, Australia

When creating her print, Sangeeta Sandrasegar became interested in the relationship between archives and memory. Through research into the First World War service records of her maternal relatives, she began to consider how we often fictionalise the past and shape histories to fit our own needs and as memory becomes ambiguous over time, we rely on archival documents to regain a semblance of history.

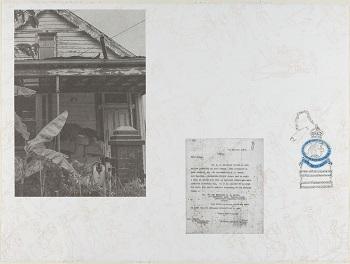

The base layer of Sandrasegar’s work contains images that reference traditional Indian temple and palace wall paintings, a reference to her Indian ancestry. Traditionally these paintings depicted Hindu and Ramayana stories or scenes from everyday life, but here they represent what Sandrasegar imagined to be the everyday experience of her relatives serving during the First World War.

The next layers contain three documentary pieces relating to her great-great-uncle Reginald Geach told through the perspective of his wife: a photograph of her house, the image of a letter sent to her in 1918, and a sketch of a badge. The letter is a copy of one found in Geach’s service records. It is from the military records office replying to enquiries into his whereabouts, as his wife had not heard from him for some time. The badge is a Female Relatives’ Badge issued in Australia to the wife and/or mother of those on active service overseas during the First World War. The work references the role of women on the home front, as well as archival connections to history and the shadowy presence of memory.