First World War marriages

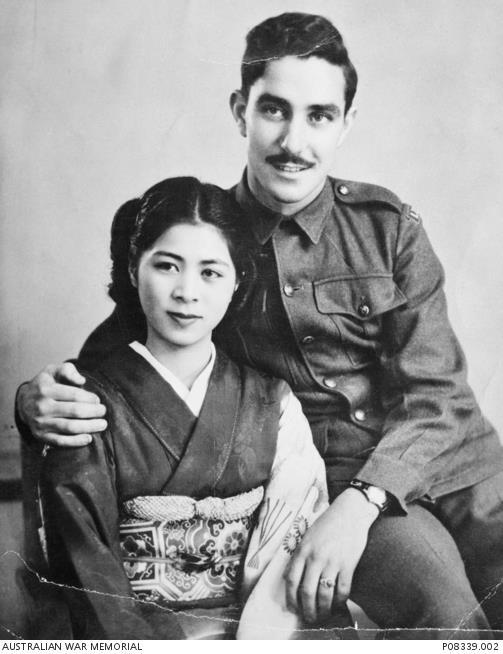

It was not uncommon for Australian soldiers to marry while serving overseas during the First World War.

After the war, a number of members of the Australian Imperial Force returned to Australia with English brides. Many of these couples met while the soldiers were hospitalised in England.

Australians also had opportunities to meet British, French and Belgian girls in France while in billets or medical facilities, during leave, or even in the camps.

Australian soldiers were popular with British girls, although not everyone approved of liaisons. Reports of bigamy led to pressure for Australian Headquarters to provide potential marriage candidates with certificates stating that men were not already married.

Weddings usually had to be planned around leave and were often rushed and lacked the usual lengthy engagement. This haste was compounded in 1919 when the Australian Government made an offer of free passage to wives of Australian soldiers whose marriages occurred before 1 September 1919.

Rationing of food, clothing and petrol in the United Kingdom were additional constraints. To achieve a traditional wedding required considerable resourcefulness.

During the early part of the war, a serviceman could only take his bride home to Australia if he paid for the journey. The large number of passengers resulting from the offer of free passage in 1919 caused enormous logistical problems and resulted in “Bride ships” sailing to Australia in 1919 and 1920. Soldiers usually accompanied their wives and children, although men and women were housed separately on the ships.

As there had been a dearth of marriageable men in Australia during the war years, overseas war brides were not always welcomed on arrival. On occasion, wives and children were not met and some abandoned brides would return home on the next ship.

Returned soldiers and their foreign-born wives and fiancées faced many challenges. In 1918 and 1919 Australia suffered from high unemployment rates, housing shortages, and an influenza epidemic which took many lives. Many Soldier Settlement properties failed due to unsuitability of the land and/or lack of expertise of the men who took up the scheme.