1918 and War Weariness

- 1918: Australians in France

- Battles

- War Weariness

Personally, I've seen too much of Hell to believe in a Heaven.

Letter, Lance Corporal A.H. McKibbin, 15 October 1918.

In 1918, the fourth year of the war, it was clear that many Australian service personnel were experiencing a sense of "war weariness", especially by those who had been there for a long time. The war had gone on for much longer than had been anticipated in 1914, and suffering and death and prolonged living in terrible conditions had become increasingly difficult to bear. This tongue-in-cheek 1918 cartoon from the AIF publication Aussie also reflected the feeling that there was no certainty that the war would be over soon.

This tongue-in-cheek 1918 cartoon from the AIF publication Aussie also reflected the feeling that there was no certainty that the war would be over soon.

This tongue-in-cheek 1918 cartoon from the AIF publication Aussie also reflected the feeling that there was no certainty that the war would be over soon.

In a letter to the family of a fellow soldier and friend who had been killed, Lance Corporal A.H. McKibbin wrote in August 1918:

Harry was shot by a sniper through the head while leading his platoon in to relieve in front of "Polygon Wood", which is about 2 miles from Hill 60 and about 7 miles from what remains of Ypres ... all that ground we fought so terribly for is now in the hands of the infernal Boche again ... From Armentieres to Nieuport, embracing the Messines and Ypres sectors, is known as the "cockpit of Europe", filled with "dead men's bones and all uncleanliness", and it stands in my mind as the "abomination of desolation" on this earth.

The death and devastation around him had sicken McKibbin. He continued:

The real fact is that I've seen so many fine lads and comrades go down that death became a constant companion and not to be dreaded ... It is not the thought of death and oblivion which terrifies a case-hardened soldier, but rather the manner in which it comes. One is talking to one's mate in action, and while in the act of answering he is called away by a bullet or piece of shell and one has to throw his broken body out of the trench to bury when a quiet time comes; poor old chap! or poor beggar! is often his only burial service.

THE FUN OF IT (excerpt)

I saw a soldier walk a parapet;

Hugely fantastic on a reddened sky,

Laughing he strode along; I called to him "fool".

He stood, and looking down into the pool,

Wherein I crouched, he answered: "No not I!

I'm wise, my lad- and I'll be wiser yet:

Live on- in slime- another hour of strife,

Maybe a day, a year- with all these Dead-

This festering life in death? If such be life-"

He paused, glanced scornfully about, above,

Then flung his hat away into the wood,

And gaily added with a sprightly wit:

"If such be life, and if to live's to love,

O God, we've made a bloody mess of it!" ...

And, as we scooped his grave, we understood.

- Henry Weston Pryce, 1918.

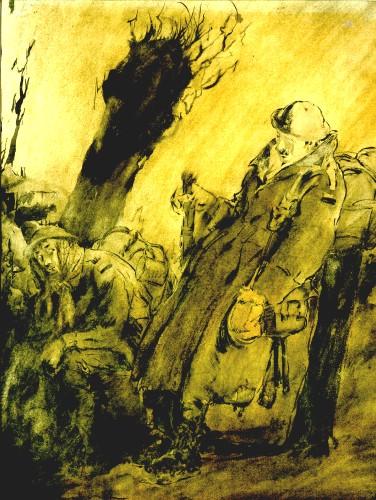

Tired, wet and disillusioned 1918, by Will Dyson. ART 02326

In July 1918, Private A. Golding was very frank about his feeling on the war:

Used to dodge shells at first, but taking second load whished (to god) that one would hit me, a piece of one came between me and the chap in front we both cursed it for not giving us a "blighty".

A week later, after a period of heavy shelling from the Germans, he wrote:

I'll own, that his shells put the wind up me, and that I'm not, and don't want to be a hero. I want to go home.

Some soldiers even displayed a sort of grim humour about the terrible situations they continued to find themselves in. Private Ronald Simpson, who was badly wounded three times during his service, wrote in October 1918:

I would not mind getting torpedoed just to see what it would be like one may as well try all the sensations of the war. I have tried all the land ones so the water would be a bit of a change for once.

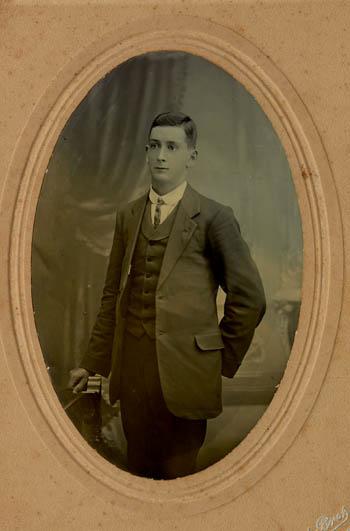

A studio portrait of Private Simpson.

Private Simpson died five days after the armistice, from pneumonia influenza. His nurse wrote a letter of condolence to his mother.

This photograph, taken at a ferry landing at Vaire-sur-Somme on 5 May 1918, with the words "Circular Quay"- the famous Sydney ferry terminal- painted on it, shows the homesickness soldiers felt.

There was a sense of disillusionment among many soldiers, a feeling of homesickness, and a loss of faith in the reason they were there and in their superiors for allowing such a war to continue as long as it had. At the end of August, Private A. Golding wrote:

the arguments this morning was about the war and the cause of it all, All came to the conclusion that it was "DOLLARS".

It was not just servicemen who were war weary. Nurse Elsie Cook wrote on 1 January 1918:

where will the next New year's day find me I wonder? And when will this beastly war be still on?

Australian troops were completely exhausted as the end of 1918 approached. During the attack on the Hindenburg Line in September, Gunner J.R. Armitage wrote:

We slept while riding our horses. We slept while walking and we slept while standing up.

On top of all of this, food was often hard to find when supplies were destroyed, and rations were also imposed. The nutritionally poor "Anzac diet" revolved around bread, tea, tins of bully beef and hard biscuits. After being shelled and gassed by Germans, and lying in a trench for a day and night, Armitage wrote in his diary:

It rained all day and most of the night and the trench got incredibly muddy and flooded. At midday two men volunteered to go to the cookhouse in the village for some food ... They made it all right but we had a very gassy stew.

The differences between Australians and the "enemy" soldiers also became less clear as the war dragged on. In 1918, Private Ernest Morton, 2nd machine Gun Battalion wrote:

We were going to hop over one day, and there was a German officer. Only a young chap, be in his late teens I suppose, and he has been mortally wounded. He prayed to me to kill him He spoke English better than I'll speak it in my life, probably educated in an English university, and it flashed through my mind then, we've been taught all these years about these heathens we're fighting and they've got to be exterminated at all costs, and here's a man that could speak English and asking me to put him out of his misery.