Great Escapes

Special Exhibition

1 March 2019 - 1 June 2019

During the First World War more than 4,000 Australians became prisoners of war. In the Second World War that number was over 30,000. Prisoners often suffered from ill-treatment, hunger, and sickness during their captivity.

A small number of prisoners spent months planning and preparing escape attempts. The issue was not only how they would escape from captivity, but how they were going to travel through enemy territory to safety. Very few attempts were completely successful. Recapture would result in punishment, often for the entire camp.

Each escape attempt was a learning experience, and subsequent attempts would increase in sophistication. Luck played an important role in many escapes. The chance to steal tools to cut through wire or distraction of the guards provided the opportunity to escape. Tunnels offered the chance for mass escapes but required skills to successfully excavate and construct the tunnel and to engineer systems for lighting and air flow. Stories of daring mass escapes from the First World War, such as from Holzminden camp in 1918, inspired similar escape attempts throughout the Second World War.

These maps, documents, and photographs illustrate just a few stories of escapes attempted during the First and Second World Wars.

Australian officers at Krefeld prisoner-of-war camp, Germany, in May 1917. P08451.002

Some stories from the exhibition

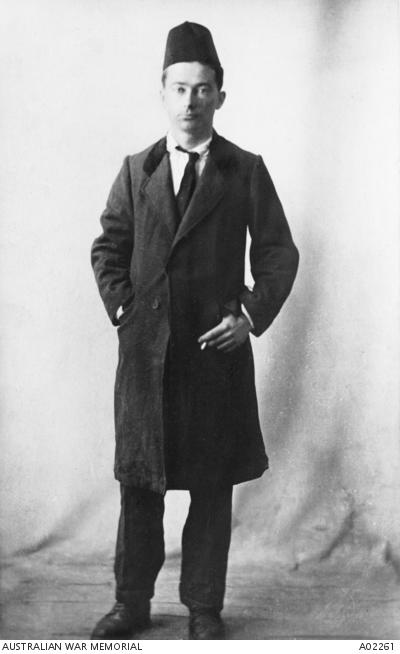

Captain Thomas White in 1918, dressed in the disguise he used during his escape. A02261

Thomas White

Around 200 Australian servicemen were taken prisoner by Ottoman forces during the First World War. Captain Thomas White was the only one to escape successfully.

White became a prisoner in November 1915 when his plane was damaged during a bombing raid on Baghdad. He spent the next two years in a prison camp at Afion Kara Hissar. In July 1918 White was moved to hospital in Constantinople. Taking advantage of the freedom to move around, White and fellow prisoner Allan Bott, a Royal Air Force captain, made preparations for an escape.

The men were being transported on a train when it crashed, and in the confusion they escaped and managed to evade recapture. After hiding for several days in Constantinople, they stowed away on a Ukrainian ship anchored in the city’s harbour, where they remained hidden for a month before departing port. White and Bott eventually made their way to Salonika in Greece. While they awaited transport back to London, the Armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, bringing an end to the fighting on the Western Front.

The exposed escape tunnel leading from the Holzminden prisoner-of-war camp, 1918. John Cash, P03473.003

Holzminden

The prisoner-of-war camp at Holzminden, Germany, opened in early September 1917. The camp held between 500 and 600 British and dominion officers, while approximately 100 to 160 other ranks were imprisoned to serve as orderlies. Conditions were severe, and numerous escape attempts were made by the prisoners. Some were successful in breaking out of the camp, but virtually all were recaptured within a matter of days.

The largest and most celebrated escape attempt was made via a tunnel on the night of 23 July 1918. It had taken the prisoners nine months to construct the tunnel, the entrance to which was concealed under a staircase in the orderlies’ quarters. The plan was for 86 officers to escape into a neighbouring field, but congestion caused the tunnel to collapse after just 29 had made it through. The remaining prisoners had to crawl backwards to the tunnel entrance.

The escape was not discovered until the following morning, when the last pair of officers to crawl out of the ruined tunnel ran into the camp Kommandant, Karl Niemeyer, who noticed their dishevelled appearance. Shortly afterwards, a local farmer arrived in a fury to report the trampling of his crops in the area surrounding the tunnel’s exit.

Of the 29 escapees, ten made it to safety in the Netherlands. The 19 recaptured prisoners were confined to their cells with bread and water rations and no lighting. On 27 September they were brought before a German military trial, where they were convicted and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for mutiny and destroying imperial government property. However, the sentence was never enforced, as Germany was now losing the war.

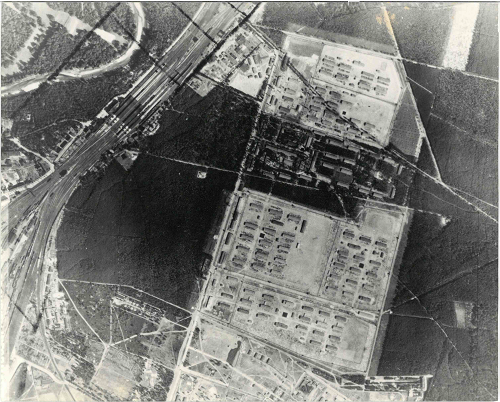

Aerial photograph of Stalag Luft III. PR03211.002

“The great escape”

One of the most well-known prisoner-of-war escape stories is the mass escape from Stalag Luft III on the night of 24 March 1944, made famous by the book and popular film The great escape.

Prisoners held in Stalag Luft III at Sagan (modern-day Poland) began work on digging three tunnels, nicknamed “Tom”, “Dick”, and “Harry”, in 1943. Tom and Dick were discovered by the guards before they could be completed, but Harry was finished in March 1944. More than 200 men were prepared to break out of the camp, but only 76 managed to get through before the escape attempt was discovered.

Three prisoners avoided recapture: two made it to neutral Sweden by train and boat, while the third reached Spain with the help of the French Resistance. Of the rest, 50 were murdered by the Gestapo. Their bodies were cremated and their ashes were returned to the prison camp. The prisoners there built a memorial to the 50 in a nearby cemetery.

Australian officers and orderlies at Oflag IV-C, Colditz Castle, 1944. P07203.001

Oflag VII-B and Colditz

In December 1942 work began in Oflag VII-B on an escape tunnel from a latrine block inside the camp to a villager’s chicken coop, about 30 metres away. The tunnel was completed in May 1943, and in early June 65 men escaped. Most of them headed south, towards Switzerland, sleeping by day and travelling by night. All were eventually recaptured, but their escape had occupied more than 50,000 police, soldiers, home guard, and Hitler Youth for a week.

The recaptured prisoners were sent to Oflag IV-C at Colditz Castle in Saxony. This camp was reserved for prisoners who had attempted escape, or who had caused enough problems for their German captors to be removed from the standard camp system. Lieutenant Jack Millett, one of the Australians who had escaped from Oflag VII-B, continued his escape committee career in Colditz, becoming the resident map-maker. He was famed for producing high-quality escape maps and essential documents for Allied prisoners attempting escape.