Telling their stories

Telling their stories explores the changing ways in which the Australian War Memorial has told the stories of Australian servicemen and servicewomen.

Conceived on the Western Front in 1916, the Australian War Memorial was established to ensure that Australians back home understood the experience and sacrifice of those who fought in the First World War. By the time it opened in 1941, the Second World War had started, and plans were already being made to expand the Memorial.

Today the Memorial presents diverse stories of Australian experiences of war across numerous conflicts. While the is past is often revisited with fresh eyes and using new technologies, the traditions and methodologies established during the First World War continue to inform our work.

Accompanying the exhibition is a series of vodcasts featuring Memorial curators talking about a story or project that has been important to them, and how they have told it. These vodcasts are available here.

Telling their Stories is the fourth and final part of the exhibition series A home on a southern hill, presented online to mark the 80th anniversary of the Australian War Memorial building, which was inaugurated on 11 November 1941.

Will Dyson, Going over the old ground with B..., Pozières, 1917

The Australian War Memorial was first conceived in 1916 by C.E.W. Bean, Australia’s official war correspondent, who accompanied the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on Gallipoli and in Europe. After witnessing the carnage on the Western Front, Bean determined that the sacrifice and contribution of the men of the AIF should be remembered and understood in their homeland. In this drawing, artist Will Dyson depicts Bean at the former battlefield of Pozières, seeking details from a soldier and an officer.

The Australian War Records Section (AWRS) Trophy Store at Péronne, 1918

Once planning began for a museum and memorial in Australia, the Australian War Records Section was established to collect documentation, such as commander’s war diaries, previously submitted to the British. Led by Captain John Treloar, the section quickly expanded to collect artefacts (known as “trophies”), photographs, film and art. This photo depicts the Australian War Records Section Trophy Store at Péronne, where battle souvenirs were collected, in 1918. The large collection – including some 25,000 objects – was shipped to Australia to form the basis of the Australian War Memorial’s National Collection. May 2017 saw the centenary of the AWRS, and with it, the centenary of the Australian War Memorial collections. The National Collection now contains over 1,170,000 items.

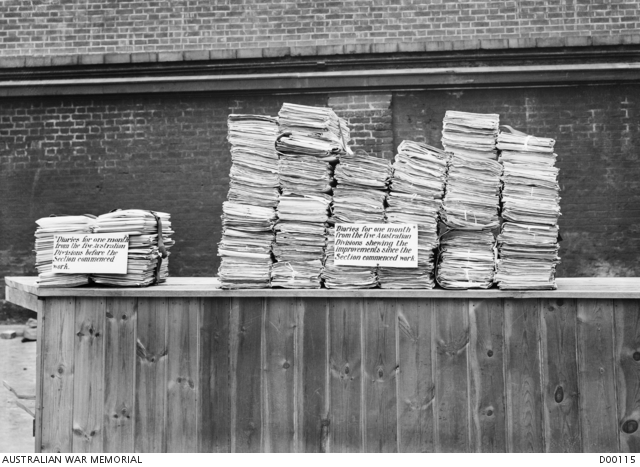

Comparison photo of war diaries, showing the impact of the Australian War Records Section

The war diaries kept by unit commanders were identified as a critical resource for understanding the activities of the Australian Imperial Force during the war. As one of its first tasks, the Australian War Record Section (AWRS) gave instructions and training on keeping war diaries. This photo shows the impact of the AWRS through two stacks of war diaries submitted by the five Australian Divisions during one month. The small pile on the left was compiled before the establishment of the AWRS, the stacks on the right were collected after its formation.

Photo of Corporal Ernest Lionel Bailey tagging battlefield trophies for the Australian War Museum at the Hoograaf Collecting Depot

Corporal Ernest Bailey was the only member of the Australian War Records Section to be killed in the course of duty in the First World War. While letters to his wife reveal that his transfer to the section likely prolonged his life (as many of the soldiers he served with were killed in action just a few days later), he was accidentally killed while attempting to remove an explosive from live ordnance so that it might form part of the collection. C.E.W. Bean observed that the future Memorial would “be a monument to him; for it is his work that thousands upon thousands of Australians will see as they walk down those galleries”.

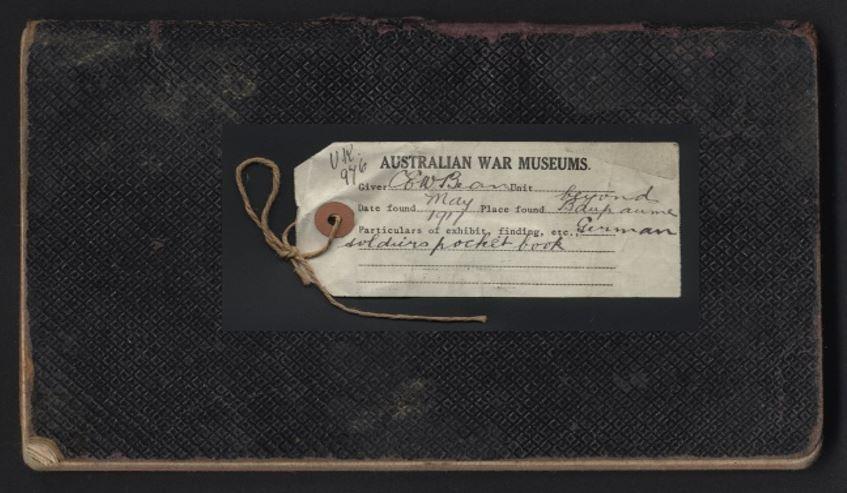

German soldier’s pocketbook with Australian War Records Section label

After the war, the head of the Australian War Records Section recalled that “every man went to action with a pocketful of museum labels”.

Motivated by patriotism and the desire to commemorate their fallen mates, the collecting efforts of the men of the AIF were so significant that the British general collecting for the Imperial War Museum later wryly observed, “your energetic people have swept the whole place clean”. While the majority of collection items have had their labels replaced as part of collection management, the label attached to this German soldier’s pocketbook remains, detailing that it was collected by C.E.W. Bean.

AWM46.193.1 & 2

Studio portrait of 5435 Private William Joseph Punch, 1st Battalion

During the First World War recruiting officers were told to exclude “Aboriginals, half-castes or men with Asiatic blood”. Nonetheless, an estimated 1,300 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men are known to have served with the Australian Imperial Force. Documents and photographs collected by the Memorial and other institutions have enabled contemporary researchers to discover and tell their stories. This studio portrait of Private William Joseph Punch appears in the Memorial’s First World War gallery. As an infant, Punch was the only survivor of a massacre carried out by white settlers. Adopted by a white farming family, Punch embarked with reinforcements to the 1st Battalion, then transferred to and served with 53rd Battalion. He died in England in August 1917 after being wounded on the Western Front, and is commemorated on the Roll of Honour.

Private William Edward (Billy) Sing in Egypt c. 1915-16

Recent research shows that although the majority of Australians in the first Australian Imperial Force (AIF) were of British ancestry, there were also significant numbers of men with different backgrounds, including Germans and Russians. This photo shows Private William Edward (Billy) Sing DCM of the 5th Light Horse Regiment. Born in Clermont, Queensland, Sing was one of about 200 men of Chinese–Australian background who served with the AIF even though recruitment legislation at the time did not allow those “not substantially of European origin” to enlist for military service. Sing became a renowned sniper on Gallipoli and was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal in 1915.

Model of Mont St Quentin in situ, 1919

The Memorial’s dioramas are amongst the most significant and moving of its displays. C.E.W. Bean and official war artist Will Dyson had seen “picture models” in British military museums, and envisaged dioramas depicting important battles as being a vital part of the future Memorial. Desiring the dioramas to be works of art that would convey the emotional tenor of the battle as well as the action, they proposed appointing artists and sculptors rather than model makers to create them. When work on the dioramas commenced, two of those appointed had fought on the battlefields the dioramas would represent. Each diorama is the result of extensive field research. This photograph shows a preliminary diorama of the battle of Mont St Quentin propped up in front of the battlefield.

The Australian War Museum exhibition in Sydney

In order to mobilise and maintain support for a future war museum, temporary exhibitions of the collection were held in Melbourne and then Sydney in the 1920s. This image shows the Sydney Exhibition Building in Prince Alfred Park. Both exhibitions were attended by large audiences, including many returned service people and their families seeking to understand the conflict they had just endured. The Memorial continues to tour exhibitions across all states and territories as part of its Touring Program.

Captain Francis Derwent Wood at Wandsworth Hospital

As well as telling the stories of servicemen and servicewomen during war, the Memorial also explores the consequences of war. While the end of the First World War was publically marked by triumph and celebration, many servicemen who returned home had sustained injuries that would have an enormous impact on their lives. This photograph by Horace Nicholls show Captain Francis Derwent Wood, an English Army medical officer, moulding a plate to the face of a serviceman to mitigate the impact of his disfigurement.

Photograph of Nora Heysen, 1945

The Second World War saw the appointment of Nora Heysen as Australia’s first female official war artist in 1943. Although there were heated debates about her rank, rate of pay, and what she would be allowed to depict, Heysen’s hard won appointment reflects the broadening of women’s roles that took place during the Second World War. When Heysen was deployed to New Guinea in 1944, she produced a large body of work, mostly focused on the work of nurses at the Finschhafen hospital, but also depicting Indigenous men who worked with the Australians. This photograph shows Heysen in her Melbourne studio in 1945, completing paintings that she had begun overseas.

Photograph of Australian soldiers on Kokoda, 1942

The Kokoda campaign of the Second World War was particularly significant for Australians because it was fought on Australian territory. Its progress was followed in Australia in part through cinema newsreels made from footage obtained by official cameramen at enormous personal risk. In this picture of members of B Troop, 14th Field Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery, pulling 25-pounder guns uphill through dense jungle with the assistance of members of the 2/1st Australian Pioneer Battalion, the fully clothed man is thought to be Australian photographer Damien Parer. Thomas Fisher, who took this photograph while part of the Military History Section of the Memorial, was killed not long after it was taken. Parer was killed while filming Australian troops in 1944.

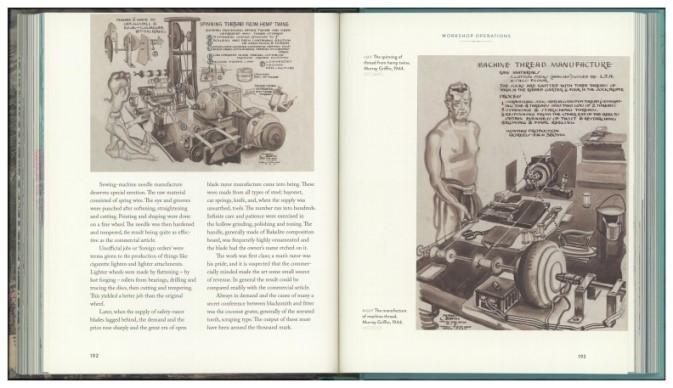

Australian War Memorial publication The Changi Book

The Australian War Memorial has a proud history of publishing that dates back to C.E.W. Bean’s official histories of the First World War. The Changi book documents the experiences of Australian servicemen in the Changi prisoner of war camp during the Second World War. These pages show artworks by Murray Griffin, an official war artist who was interned at Changi from 1942 until the end of the war. Griffin’s works show the complexity of life at Changi and the resourcefulness of the men in improving their own conditions. Griffin’s own resourcefulness made his work possible; when his materials ran out he ground clay to make pigments.

RC11576.053

Ken McFadyen, Airlift, 1968

Ken McFadyen’s painting of Australian troops entering a Chinook helicopter in Biên Hòa Province in Vietnam shows the changing relationship between people and machinery as modern warfare developed. Helicopters quickly became emblematic of the war in Vietnam, so widespread was their use for moving troops in and out of difficult terrain. This painting conveys the chaos and noise of the large machine which dominates its composition. Ken McFadyen was working as a set designer for the Australian Broadcasting Commission when he was appointed as an official war artist. He undertook jungle warfare training in Queensland before travelling to Vietnam and was expected to perform as a combat soldier if required.

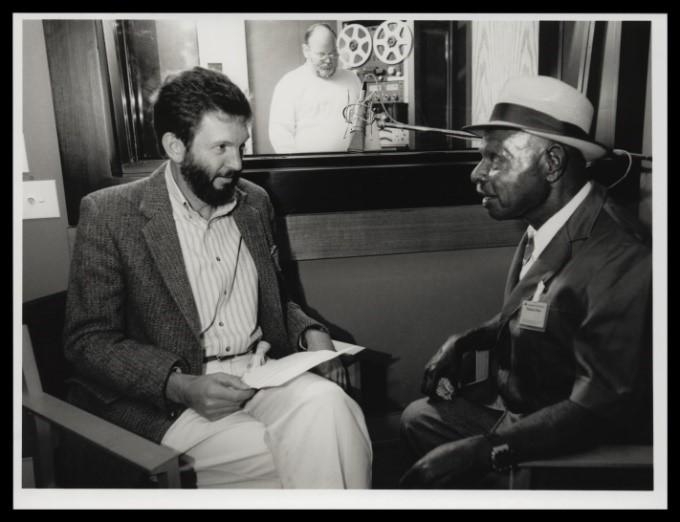

Lance Corporal Saulo Waia being interviewed by Dr Robert Hall, 1991

Recorded oral history interviews allow the Memorial to capture first-hand accounts from Australia’s servicemen and servicewomen. This photo shows Lance Corporal Saulo Waia, who served with the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion during the Second World War, being interviewed by Memorial Research Officer Dr Robert Hall in 1991. Lance Corporal Waia, who was born on the island of Saibai in the Torres Strait, explained that as there is only a small channel between Sabai and Papua New Guinea, he and his six brothers joined up to protect their home from Japanese invasion.

RC11576.053

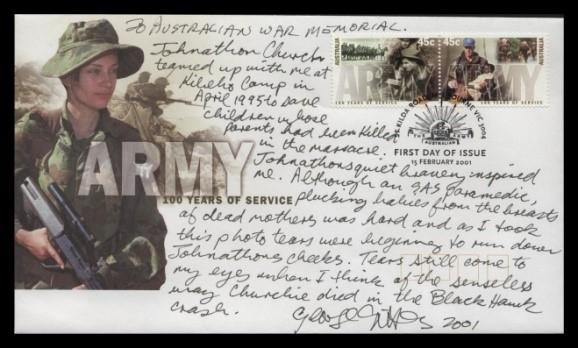

Letter to Australian War Memorial from George Gittoes

The Memorial commemorates individual service at the same as it tells the broader stories of conflict. This letter was written to the Memorial by official war artist and defence photographer George Gittoes in 2001. The envelope on which it is written bears a stamp featuring a photograph of SAS Trooper Jon Church at Kibeho Camp in Rwanda in 1995. The photo was taken by Gittoes while he was deployed to document Australia’s involvement in peacekeeping activities. Trooper Church died the following year during training in an SAS Black Hawk helicopter crash near Townsville. The stamp triggered Gittoes’ memories of the Rwandan peacekeeping, and he wrote this letter in tribute to Trooper Church, whose “quiet bravery” had inspired him.

The Memorial holds thousands of letters and diaries, and now also collects emails and other digital-born documents.

PR01779

Lyndell Brown and Charles Green, View from Chinook, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, 2007

In recent times, artists and soldiers frequently experience conflict from the air. Deployed as official war artists in Afghanistan and Iraq, Charles Green and Lyndell Brown depict the view from a Chinook helicopter during a supply mission flight to an outpost in Helmand province. Artist Lyndell Brown explains: “It's an extraordinary thing to be hurtling through space, fifty feet off the ground – very low, very fast – across this rocky landscape.” The heavy black frame of the helicopter window draws attention to the fact that much of what the artists saw on deployment was viewed from military vehicles.

Lyndell Brown and Charles Green, Route Irish, Baghdad, 2007

This painting of a Humvee stopped beside the road, visible through the windscreen of an armoured Rhino Runner bus, depicts a moment of uncertainty on Route Irish, Baghdad. Artist Lyndell Brown explains: “Route Irish is supposedly the most dangerous road in the world. And here you see an American Humvee stop, and you see a soldier; it looks like he's getting out of the Humvee but you don't know what's going on.”

Photograph of Shaun Gladwell, 2009

This photograph of official war artist Shaun Gladwell was taken by Memorial curator Nick Fletcher, as the pair were returning to Tarin Kowt in a Bushmaster after a logistics run to Patrol Base Wali in Uruzgan Province, Afghanistan. Contemporary official war artists continue to be embedded with active service personnel; as the nature of conflict has evolved, so has the role of the war artist. Pictured here with the base boundary wall in the background of the image, Gladwell is identified as an official war artist by the patch on his upper arm.

Mission brief, Kamp Holland, Tarin Kot, 2012

In this image, official war photographer Stephen Dupont draws attention to the changing technologies that present challenges and opportunities for both the Australian Defence Force and the Australian War Memorial as we preserve and tell their stories. Inside Kamp Holland, members of the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment, participate in a mission brief for the next day's patrol. Amid stacks of rolled documents, they pore over a map that illuminates one man’s face with a blue glare. Dupont’s time in Afghanistan in 2012 was his second appointment as an official photographer; in 2003 he documented Australian-led peacekeeping efforts in the Solomons.

Trench art clock made by Sapper SK Pearl

Sapper Stanley Keith Pearl made this alarm clock in France during the First World War by combining salvaged materials, including brass shell cases, a German bullet, and an Australian Rising Sun badge, with a commercially produced mechanism. This alarm clock and other items made by Sapper Pearl formed the heart of the Art Gallery of South Australia’s recent exhibition Sappers and shrapnel: contemporary art and the art of the trenches, which commemorated the centenary of the First World War by highlighting the human impulse to creativity. This use of Sapper Pearl’s work shows how value and meaning of collection items may be layered or re-made by different generations.

Richard Lewer, The Angel of Mons, 2016

After seeing the dioramas at the Australian War Memorial, artist Richard Lewer worked with model builder Tony O’Connor to visualise the story of the Angel of Mons – said to have appeared in the sky to safeguard the British retreat from Mons in August 1914 – in the form of a small diorama. Lewer created a series of six dioramas that depict moments during and after the First World War for an Art Gallery of South Australia exhibition inspired by First World War trench art. Now part of the Memorial’s collection, they are both a continuation and a reinvigoration of the diorama tradition.

AWM2017.120.2

Ceremonial dancer at the installation of the APY Lands Commission, 2017

Fiona Silsby’s photograph of a ceremonial dancer in front of Kulatangku angakanyini manta munu Tjukurpa [Country and Culture will be protected by spears], highlights the most significant change in the Memorial’s storytelling of recent years: the presentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander defence of country. The painting was commissioned by the Memorial and painted by artists from the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara lands in South Australia. Its installation in Memorial’s Orientation Gallery contrasted with the Memorial’s Colonial Galleries, installed in the 1980s and now removed, which briefly mentioned Australia’s frontier wars by explaining that Australia’s first garrison “suppressed Aboriginal resistance to white settlement”. The brutality of Aboriginal dispossession is explicitly acknowledged in more recent exhibits.