Colonial period, 1788–1901

British settlement of Australia began as a penal colony governed by a captain of the Royal Navy. Until the 1850s, when local forces began to be recruited, British regular troops garrisoned the colonies with little local assistance. From 1788 marines guarded English settlements at Sydney Cove and Norfolk Island; they were relieved in 1790 by a unit specifically recruited for colonial service, and in 1810 the 73rd Regiment of Foot became the first line regiment to serve in Australia. From then until 1870, 25 British infantry regiments and several smaller artillery and engineer units were stationed in the colonies. One role of the troops was to guard Australia against external attack, but their main job was to maintain civil order, particularly against the threat of convict uprisings, and to suppress the resistance of the Aboriginal population to British settlement.

Starboard side representation of the brig sloop HMS Pelorus, which was based at Sydney from 1838 to 1839.

With the end of convict transportation to New South Wales in 1840, the need for military forces diminished and troop strength began to decline, particularly as British troops were required in the first Anglo–Maori wars in New Zealand and as colonial police forces were formed. After the last British regiment left in 1870 the colonies were obliged to assume responsibility for their own defence. Only rarely during their time in Australia did British troops fire upon fellow Europeans. In March 1804 British regulars suppressed a convict rebellion near Castle Hill, and in 1829 soldiers were involved in putting down the "Ribbon Gang" outbreak near Bathurst. In an incident that took place after transportation had ended, British troops, along with police, battled insurgent miners at the Eureka Stockade, on the Ballarat goldfields, on 4 December 1854.

British soldiers based in Australia who did partake in military operations were more likely to have fought across the Tasman in the Anglo–Maori wars of the 1840s and 1860s. Resulting from the continuing expansion of European settlers onto Maori land and the colonial government's determination to crush native independence, the first war took place in 1845–46. With insufficient troops in New Zealand to meet the threat, the 58th Regiment of Foot, then based in Australia, was dispatched in February 1845, soon to be followed by further troops. Fighting died down after 1846 but flared again in 1860 before a truce was declared and peace returned.

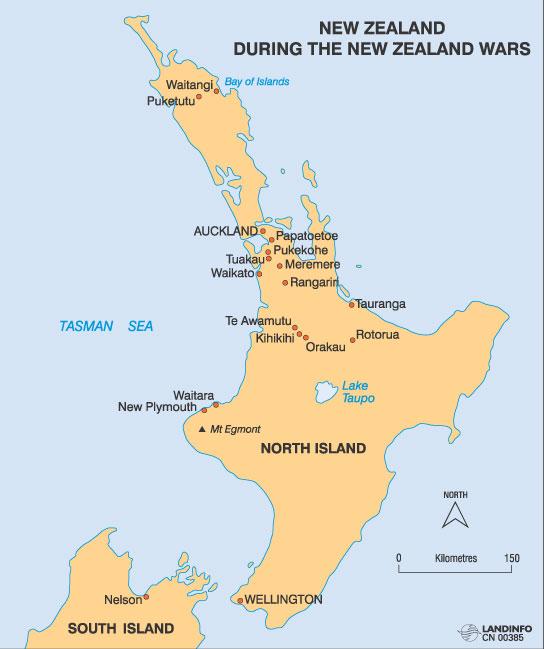

New Zealand during the New Zealand Wars - North Island

By 1863 hostilities had reignited, and New Zealand's colonial authorities requested further assistance from Australia. A contingent of British troops was dispatched, along with Her Majesty's Colonial Steam Sloop Victoria. In July 1863 British troops invaded the Waikato area and news of the continuing campaign spread through the Australian colonies. Some 2,500 volunteers offered their services on the promise of settlement on confiscated Maori land by New Zealand recruiters; most joined the Waikato Militia regiments, others became scouts and bush guerrillas in the Company of Forest Rangers. Few of these volunteers were involved in major battles, and fewer than 20 were killed.

Despite the preponderance of British troops in the Australian colonies, colonial military forces were maintained from as early as December 1788, when the commandant of Norfolk Island, Phillip Gidley King, ordered his free male settlers (numbering six) to practise musketry on Saturdays. The first military unit raised on the Australian mainland appeared in September 1800, when Governor Hunter asked 100 free male settlers in Sydney and Parramatta to form Loyal Associations (English volunteer units raised to put down civil unrest) and practice military drills in case the Irish convicts rebelled. Six years later Governor King recruited six ex-convicts as the nucleus of a military bodyguard, creating the first full-time military unit to be raised in Australia. Both these groups joined British regulars in suppressing the Castle Hill uprising.

An officer of the 50th Regiment of Foot who was stationed at Victoria Barracks, Sydney, between 1866 to 1869, following service in the New Zealand wars. Insignia on cuff and collar indicates the rank of captain and the medals are for service in the Crimean War.

Not until 1854 were volunteer corps and militia again formed in the Australian colonies, but news of war between Britain and Russia in the Crimea led to the establishment of volunteer corps in some colonies and the formation of informal rifle clubs in others. When the Crimean War ended in 1856 volunteer units faded, to be revived in 1859 when it appeared that Napoleon III was preparing to invade England. By early 1860 most suburbs and towns in Australia supported a volunteer unit, usually a rifle corps.

An informal group photograph of spectators and competitors taken during a rifle shooting competition between ten men of the Hobart Town Volunteers Artillery and ten men from the First Rifles. The men are all holding pattern 1853 .577 inch Enfield rifles. Tasmania, 17 October 1863.

For the rest of the century volunteer corps became more organised, with instruction duties placed in the hands of professional soldiers. In the early 1890s several thousand citizen soldiers were mobilised in eastern Australia to assist regulars and police to maintain order during the maritime and shearing strikes of the early 1890s. In 1899 trained citizen soldiers were given the opportunity to test their skills in the Boer War, to which the colonial governments, and later the Commonwealth, sent contingents. The administration of colonial military forces passed to the Commonwealth on 1 March 1901, following federation.

Although much of the military training undertaken by volunteers in the colonies was aimed at meeting external threats, European settlement was accompanied by a protracted and undeclared war against Australia's Indigenous inhabitants. Fighting was localised and sporadic, following the frontiers of European settlement across the continent and continuing in remote areas of central and Western Australia until the 1930s. British soldiers (as distinct from armed police and civilians) became involved only rarely, notably during the period of martial law in Tasmania between 1828 and 1832, and in New South Wales in the mid-1820s and late 1830s. Military authorities did not usually regard Aborigines as posing sufficient threat to warrant the expense of committing military forces to pursue them, and most of the fighting was conducted by the settlers, assisted by police.

The conflict between Europeans and Aboriginal Australians followed a broadly similar pattern. At first, the Aborigines tolerated the settlers and sometimes welcomed them. But when it became apparent that the settlers and their livestock had come to stay, competition for access to the land developed and friction between the two ways of life became inevitable. As the settlers' behaviour became unacceptable to the Indigenous population, individuals were killed over specific grievances; these killings were then met with reprisals from the settlers, often on a scale out of proportion to the original incident. Occasionally Aborigines attacked Europeans in open country, resulting in encounters somewhat akin to conventional battles, usually won by the Europeans. Resistance was more successful when Aborigines employed stealth and ambush in rugged country. In addition to guerrilla tactics, Aborigines also engaged in a form of economic warfare, killing livestock, burning property, attacking drays which carried supplies, and, in Western Australia in the 1890s, destroying telegraph lines.

It is estimated that some 2,500 European settlers and police died in this conflict. For the Aboriginal inhabitants the cost was far higher: about 20,000 are believed to have been killed in the wars of the frontier, while many thousands more perished from disease and other unintended consequences of settlement. Aboriginal Australians were unable to restrain – though in places they did delay – the tide of European settlement; although resistance in one form or another never ceased, the conflict ended in their dispossession.

Three officers of the South Australian Company, c. 1899, wearing full dress. The helmet with feather hackle was worn in India and Australia in place of the traditional feather bonnet, as a concession to the climate. In the centre is Lieutenant James Stevenson-Black. The uniform he is wearing is held by the Memorial.

Further information is available on this web site. You can use Collection search to identify photographs and works of art from this era, as well as records of other collection items.

Sources and further reading:

R. Broome, "The struggle for Australia: Aboriginal–European warfare, 1770–1930", in M. McKernan and M. Browne (eds), Australia: two centuries of war and peace, Canberra, Australian War Memorial and Allen and Unwin, 1988

P. Dennis, et al., The Oxford companion to Australian military history, Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1995

Kit Denton, For Queen and Commonwealth: Australians at war, vol. 5, Sydney: Time-Life Books Australia, 1987

J. Grey, A military history of Australia, Melbourne, Cambridge University Press, 1990

H. Reynolds, The other side of the frontier: Aboriginal resistance to the European invasion of Australia, Ringwood, Vic., Penguin, 1982

P. Stanley, The remote garrison: the British army in Australia, 1788–1870, Kenthurst, NSW, Kangaroo Press, 1986

Craig Wilcox, For hearths and homes: citizen soldiering in Australia, 1854–1945, St Leonards, NSW, Allen and Unwin, 1998