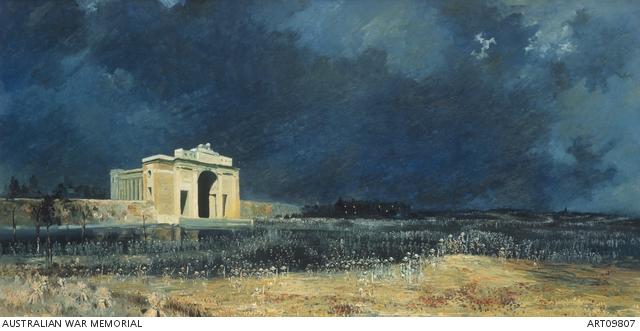

Menin Gate at midnight

Will Longstaff, Menin Gate at midnight, painting, 137 cm x 270 cm, 1927, ART09807

When war artist Captain Will Longstaff came across Mary Horsburgh during his evening walk at Hellfire Corner more than 90 years ago, he could not have imagined the brief encounter would help inspire his most famous work, Menin Gate at Midnight.

When he asked her if he could be of assistance, she said simply: “No, I just want to be with my dear boys. I can feel them all around me.”

It was 23 July 1927, the night before the opening of the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing in Ypres, Belgium. Mary Horsburgh, who had run a British canteen near the entry to the trenches at the infamous Ypres Salient during the First World War, regarded all of the soldiers as “her boys”.

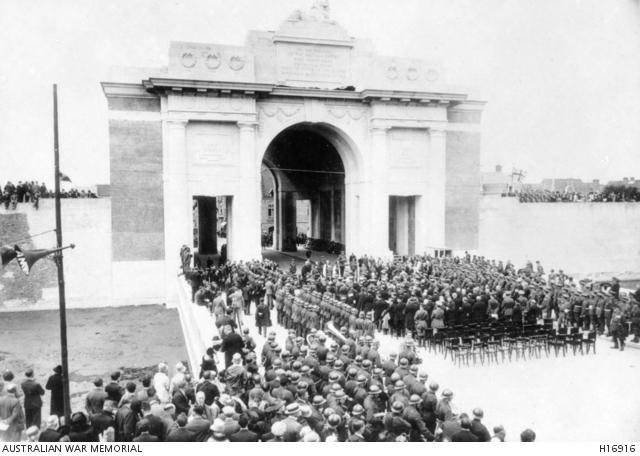

The following day, Longstaff and Horsburgh were among the 15,000-strong crowd attending the opening of a memorial which bears the names of more than 54,000 allied soldiers — including more than 6,000 Australians — who died on the Western Front and have no known grave.

Standing on the spot where countless soldiers had passed through on their last march to the front, Field Marshal Lord Plumer declared it had been resolved at Ypres — where so many of the missing were known to have fallen — to erect a memorial worthy of them; a memorial that would express the nation’s gratitude for their sacrifice, and sympathy with those who mourned. He added, “It can be said of each one in whose honour we are assembled here today: he is not missing; he is here.”

Longstaff was so profoundly moved by what he witnessed at the memorial that he was unable to sleep that night. When he returned for a midnight walk along Menin Road, he reportedly saw a vision of the dead – steel-helmeted spirits rising from the moonlit cornfields around him.

On returning to his studio in London, he painted Menin Gate at Midnight in a single session.

Having served in the Boer War and the First World War, Longstaff knew all too well the pain and loss that so many had endured during the war.

An artist from country Victoria, Longstaff had enlisted in October 1915 and served with the 1st Australian Remount Unit in Egypt. In October 1917 was invalided to England where he later trained in camouflage work with fellow Australian artists Frank Crozier and James F. Scott. He was appointed as an Official War Artist working as officer in charge of camouflage for the 2nd Division in France and was Mentioned in Despatches for his distinguished service.

After the war, he joined a group of artists working for the Australian War Records Section at St John's Wood Studio in London, preparing material for display in the proposed Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

Today, Menin Gate at Midnight is one of the most recognisable artworks in the Memorial’s collection.

The Memorial’s head of art, Laura Webster, said the painting’s tribute to sacrifice and spiritualist overtones struck a chord with many who had lost family and friends during the war.

“The painting retains its ability to provoke an emotional response and to communicate the scale of the loss of life and the devastation of war,” she said.

“In the past people responded to the painting as it related to the loss of a loved one and their own personal grief, but now the painting communicates the loss experienced by a whole generation – the vast number of those who were killed, and the immensity of the damage wrought during the First World War.”

The painting was originally bought by Lord Woolavington in 1928 for 2,000 guineas – a considerable sum at the time – and presented to the Australian government.

After being displayed in London, it was taken to Buckingham Palace for a private viewing by King George V and his family, and shown in Manchester and Glasgow.

It was then displayed in capital and regional cities around Australia, where it was seen by record crowds.

Australians queued for four hours to get a glimpse of the painting and a model of the Menin Gate memorial.

For many, it was the closest they would get to visiting the the memorial that had been dedicated to their fallen loved ones.

Like Mary Horsburgh, they wanted to feel the presence of their dear boys.

Research a family member, explore interactive digital experiences, listen to podcasts, and watch videos about the amazing objects that make up the National Collection at the Memorial.

To learn more visit www.awm.gov.au/visit/museum-at-home