'It was just like winning the lottery'

At 100 years of age, Cecil Fish still remembers the end of the Second World War as if it was yesterday.

For Cecil Fish, Friday the 13th is a lucky day. A sapper during the Second World War, he narrowly escaped death on that date when a sentry opened fire on him as he returned from posting a bunch of letters.

“We were at Wewak, and we were about five or six kilometres out from the beachhead,” he said.

“The officer said, ‘You can go down to the beachhead and post your letters, but you’ve got to protect yourself.’

“There were about four or five of us, and I was driving, and I said to the boys, ‘Look, I’ll put the letters in.’ It was a narrow road … and there was a sentry guard there. I walked over to him, and I said, ‘Look bud, I’m only going to post some letters, but don’t worry, there’s no Japanese here.’

“I might have spoken to him for 30 or 40 seconds, and then I had to go about another 10 or 15 yards to put the letters in the post box at the headquarters.

“It was a moonlit night and I was walking back down the centre of the road. I wouldn’t have been 20 foot away from him when the sentry opened fire on me.

“He thought I was Japanese, and he opened fire with an Owen gun … I dived in behind the truck and hid behind the wheels so that he couldn’t pip me.

“He put the whole 32 rounds after me, but he never hit me once, and do you know what? The major there never came to me and said, ‘Are you alright?’

"No one ever mentioned it, and that was the 13th – a Friday – so I reckon 13 is a good number.”

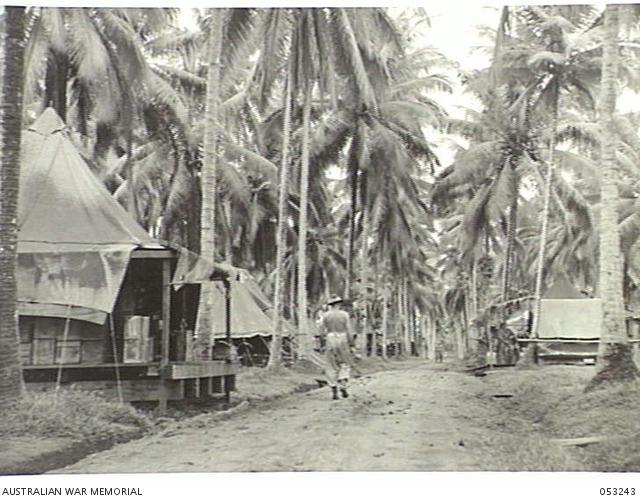

Milne Bay, New Guinea, 1943. Looking down the centre of 'Doctown', the camp area of the 2/3rd Australian Docks Operating Company, Royal Australian Engineers. The AIF tents are all raised off the ground.

Milne Bay, New Guinea. 1943. Members of the 21st Field Company, Royal Australian Engineers, building a new bridge across Lauiam Creek. The previous one had fallen down.

Known to his family and friends as “Bob”, Cecil Robert Fish was born in country New South Wales in June 1920. He joined the Citizens Military Force in October 1941, and transferred to the Australian Imperial Force in January 1943, serving as an engineer with 1 Field Squadron, Royal Australian Engineers.

“I was born down near Temora in a little place called Quandary,” he said.

“They tell me it was a Thursday, and it was a dust storm, and there was a midwife because that’s all there was. My mother had 11 children, and I was nearly the middle one, but I’m the only one that’s left now.”

He left school at 14 and was working for himself in Sydney when the Second World War broke out.

“They sent me a letter, and they said, ‘You’re in the army now, son,’ and that was it,” he said.

“I was a pretty versatile person, and I could take the good with the bad, so I just went with the flow. You were in the army, and you just accepted it.”

Milne Bay, Papua, New Guinea, 1944. Members of the 1st Field Squadron, Royal Australian Engineers, slide a 6,000 gallon diesel oil tank into position.

Milne Bay, Papua, New Guinea, 1944. Members of the 1st Field Squadron, Royal Australian Engineers, slide a 6,000 gallon diesel oil tank into position.

He remembers arriving in Milne Bay in August 1943.

“We got there after the Japanese got kicked out, and all you could see was coconut trees,” he said.

“We built installations for petrol – all sorts of tanks, wharfs, everything – but mostly we were always working, building roads, building bridges, and just being ordinary engineers.

“Every day at three o’clock, you would get a great big storm, and the creeks would run, and wash you away.

“But it’s just like everything else, you have to improvise … and we built everything we wanted there.”

Minga Creek, Wewak area, New Guinea, 1945. A bridge being constructed by 2/8 Field Company, Royal Australian Engineers.

He went on to serve during the Aitape-Wewak campaigns and came face-to-face with a Japanese soldier at Aitape.

“We had Bren guns in them days, and the ends of the tracks in New Guinea were very narrow, so you would put a couple of tins out there, and if those tins rattled, you just opened fire with the gun,” he said.

“One day there was eight of us out doing a job – way, way, away from the units – and we didn’t take any precautions to protect ourselves.

“We must have been 10 or 12 miles [16–19 kilometres] out, into the island, and we said to ourselves, ‘There’s no one here.’

“We were working away, patching this road up, and trying to get it so that they could get across it, when a Japanese soldier walked out of the forest.

“He had a gun, and all our guns were back at the truck because we were just working away as engineers.

“There was a bit of a stand-off: he had the gun, and we must have been 50-60 yards [45–54 metres] from ours, but he didn’t seem as if he wanted to point the gun at us, so at any rate, we plucked up enough courage, and we took the gun off him.

“He was just hungry, and he was as white as a ghost, but we couldn’t speak Japanese, and he couldn’t speak Australian, so there was a bit of a silence for a little while, but he understood we were friendly, and we gave him something to eat, and we gave him some water, and we sat him down.

“One bloke stopped with him to make sure he didn’t run away, and we finished our job, and took him back to the headquarters, and that was it, but what happened to him, I don’t know.

“We were just lucky, and you can’t do anything about that; you’re either lucky or you’re not.”

Cape Wom, New Guinea, September 1945. Lieutenant-General Adachi, Commander 18 Japanese Army in New Guinea, handing over his sword to Major-General H.C.H Robertson, Officer Commanding 6 Division.

Cecil was at Wewak when the war ended in 1945.

“We were about 15 kilometres inland, and the Japanese had Tokyo Rose on the air every night,” he said.

“She used to spruik all this rubbish about what was happening in Australia, and they’d listen to it on the radio every night.

“But we saw the Japanese general hand his sword over, and we had a victory dinner of corned beef, and hard biscuits with tea and coffee.

“It was just like winning the lottery – it’ll never repeat itself – and it’s something you will never see again in life.”

HMS Implacable approaching No 2 Wharf at Woolloomooloo in Sydney in December 1945.

Cecil returned to Australia on board the aircraft carrier Implacable and was discharged in 1946.

He met and married his wife Edna during the war, and has six children, 12 grandchildren and ten great-grandchildren.

At 100 years of age, he still lives independently in Sydney and loves to share his stories with family and friends.

“You do these things and you think nothing of it,” he said. “But I did the job that I was sent to do, and I was happy, I suppose, to be going home.”

Able Seaman Boatswains Mate Erica Fish marches down Elizabeth Street with her grandfather Cecil Fish during the 2016 Anzac Day march in Sydney, NSW. Photo: Courtesy Defence