'I’ve been very, very lucky'

Dr Edward Fleming during the Second World War. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

Dr Edward Fleming was a 19-year-old training to be a Lancaster bomber pilot when he and his crew became horribly lost in bad weather over Britain during the Second World War. The flight almost ended in tragedy.

“We were in a Wellington, and we had been briefed to do a cross country operation down to Land’s End, then up to St David’s Head, and then back inland to a bombing range, and home,” Dr Fleming said.

“Our base was a place called Moreton-in-Marsh, and we set off heading towards Land’s End, but we ran in to appalling weather and got pushed right back towards Europe.

“In the end, some of our navigation aids failed, and we became completely lost at night, with no idea whatsoever of where we were.

"I had an instructor on board at the time and he broke the rules and gave a mayday call.

Avro Lancaster. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

Moreton-in-Marsh. Back row: Alf Birt, Edward Fleming, John Coffey. Front: Eddie Walsh, Tas Haines, Hal Parkes. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

The crew at 1661 Heavy Conversion Unit, Winthorpe. Back row: Alf Birt, Tas Haines, John Coffey, Edward Fleming. Front Row: Hal Parkes, Ken Mason, Eddy Walsh. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

“He was an Englishman, and he had already completed operations, and had a Distinguished Flying Cross, and he did the unpardonable thing in the end which saved our lives.

“He started circling, and once you do that, the navigator can no longer keep a plot of where you are going – you can’t draw a plot of an aircraft going around in circles, you’ve got to have straight lines – and that meant we were absolutely, totally lost.

“It was dark as anything – lightning and so forth – and in the end he broke orders and issued the mayday call.

“A RAF fighter station on the south coast of England at a place called Warmwell – a fighter field; grass, no runway – answered us and put on their lights.

“We came in and landed there at about four o’clock in the morning, almost out of fuel, and we got away with it, but we had no right to survive that night.”

The Crew at Moreton-in-Marsh. Back: Alf Birt, Edward Fleming, John Coffey. Front: Eddie Walsh, Tas Haines, Hal Parkes. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

Alf Birt, Eddie Walsh, Edward Fleming, John Coffey, Hal Parkes. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

The then 19-year-old Dr Fleming had learnt to fly in Tiger Moths with the Royal Australian Air Force before he could even drive a car. By 1944, he was flying Lancaster bombers over England with Bomber Command during the Second World War.

Now in his 90s, Dr Fleming looks back on his service as one of the most significant times of his life.

“Flying anything is an enjoyable experience, but the Lancaster in particular was such an iconic aircraft,” he said. “It was very highly powered and very manoeuvrable and very sensitive … It was a lovely aeroplane to fly.”

Dr Fleming was born in St Kilda in January 1925 and educated at Wesley College, Melbourne. He was a member of the Air Training Corps in his final two years there and enlisted in February 1943. His father Wilfred Fleming had served with the Australian Army Medical Corps during the First World War.

“I was in the crew that won Head of the River in 1942, and in 1943 I turned 18,” Dr Fleming said. “We had to join up, so I elected to join the air force. I’d been in cadets at the school during my school days, and I hated cadets in the army, and I got very sea sick, so the navy was out, but we had some friends whose sons were in the air force already, and they spoke very well of it, particularly air crew, so that was the choice I made, and I’ve got no regrets.”

Pilots learned to fly in a Tiger Moth. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

DH82 Tiger Moth. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

He completed his preliminary training at No. 2 Initial Training School, Bradfield Park, and was selected for pilot training. He learnt to fly in Tiger Moths at No. 11 Elementary Flight Training School, Benalla, and was posted to No. 6 Service Flying Training School, Mallala, flying Avro Ansons.

“Almost everyone who joined the air force wanted to be in air crew,” he said.

“And of the air crew, most wanted to be pilots, and fortunately, I got picked for that.

“You had to work out on the airfield – starting up aircraft, refuelling, and so forth – and then you started flying Tiger Moths.

“You then went on to fighter aircraft or on to bomber – multiple-engine – aircraft and I was chosen to go on to heavy aircraft.

“We flew Avro Ansons – a clumsy old aeroplane – but it was an easy one to fly … and I enjoyed it tremendously.”

D2 Flight, 38 Course, 11 EFTS, Benalla, 1943. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

Aircrew training at Benalla, 1943. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

An Avro Anson. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

An Avro Anson. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

An Airspeed Oxford. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

When he went home on leave, he learned that he had been flying for months with a broken arm.

“We were doing ground duties in the first month we were there and to start the Tiger Moths up you had to swing the airscrew,” he said.

“This chap had been flying, and we refuelled his aeroplane. I tried to start it in the ordinary way, but it wouldn’t start, and that meant the engine was too hot.

“You had to swing the airscrew the other way to empty out the petrol from the carburettor, and to do that, you gave the pilot the order to switch off.

“Unfortunately, he did not switch off, so when I swung it back, the airscrew kicked straight over. It threw me onto the ground, and I busted my radius, but it was never treated.

“The MO said it was just bruised, and when I went home on leave, my father, who was an oral surgeon in Melbourne, X-rayed it with his dental machine.

“It’s healed alright – there’s just got a bit of a lump there now – but it was an interesting business.”

Edward Fleming in full flying kit at Eastbourne with the family dog Tony. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

Edward Fleming, right, in Sydney in 1943. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

In January 1944, he sailed for Britain aboard the troopship New Amsterdam. In England, he trained on Tiger Moths and Airspeed Oxfords, and was posted to 21 Operational Training Unit, Moreton-in-Marsh, where he learnt to fly Wellington bombers and acquired a crew.

“It was a funny business,” he said. “The whole station was called into the gymnasium as a rule, and you were told to pick someone to be your navigator … your wireless air gunner, and so forth. It was so haphazard, but it worked remarkably well.”

He was flying a Wellington when disaster almost struck.

“We had one bad experience, which was my fault entirely,” he said. “I did a very bad landing, and tried to do what they call a ‘go around’.

“We should have hit the Morton-in-Marsh church steeple, but we just crawled over it … so we were lucky – very lucky.”

On board New Amsterdam. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

Little room to move. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

He remembers being posted to 1661 Heavy Conversion Unit at Winthorpe, Lincolnshire, where they converted to Lancaster bombers and acquired a flight engineer. Their training consisted of long cross-country flights, by day or night, distributing aluminium foil (window), and conducting practice bombing.

“Only the flight engineer in our crew was British, the other six of us were Australians,” he said. “It must have annoyed him to no end having to fly with a colonial captain and a colonial crew.”

They were posted to 550 Squadron, RAF, at North Killingholme, Lincolnshire, shortly before the cessation of hostilities in Europe. Dr Fleming admits he was initially disappointed to have missed out on taking part in operations over Europe, but later realised his good fortune.

“We were all geared up to get into it and hit the Germans, and I felt disappointed,” he said.

“I had just turned 19, and you had this feeling of indestructibility at that age.

“You’re indestructible, absolutely indestructible – it can’t happen to you – so I was very keen to get into full operations, but in retrospect, I have absolutely no doubt that we would not have survived in major operations for very long …

“The casualty rate was enormous.”

Edward Fleming, left, in Sydney in 1943. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

Vickers Wellington. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

Vickers Wellington. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

More than 55,000 members of Bomber Command were killed during the Second World War, in raids over enemy-controlled Europe, training exercises and accidents on the ground. Of the 10,000 Australians who served with Bomber Command, more than 3,400 never returned.

Dr Fleming was one of the lucky ones. He returned to Australia and was discharged in January 1946. He studied medicine the University of Melbourne under the Commonwealth Repatriation Training Scheme, and graduated in 1952.

“There were so many ex-servicemen wanting to go to the university, they relocated medicine and dentistry and engineering up to Mildura and took over the RAAF training airfield,” he said. “They converted the old air force hangars into lecture theatres, and those faculties did their first year up there to deal with the huge influx of ex-servicemen wanting to do degrees.”

He entered general medical practice at Traralgon, Victoria, and married his wife Barbara in January 1956. They had two children before sailing to England, where Dr Fleming obtained Fellowships of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons of Edinburgh and England. They had two more children in England, and in 1966, Dr Fleming and his young family moved back to Australia. They settled in Canberra, where he practiced as a general surgeon. He joined the RAAF Reserve as a senior surgical specialist working at RAAF Fairbairn, deploying as locum surgeon to 4 RAAF Hospital, Butterworth. He was also involved in medevac flights from Vung Tau during the Vietnam War. He retired from the RAAF Reserve in 1980 and continued to fly until 1990.

Edward Fleming in Melbourne in 1946. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

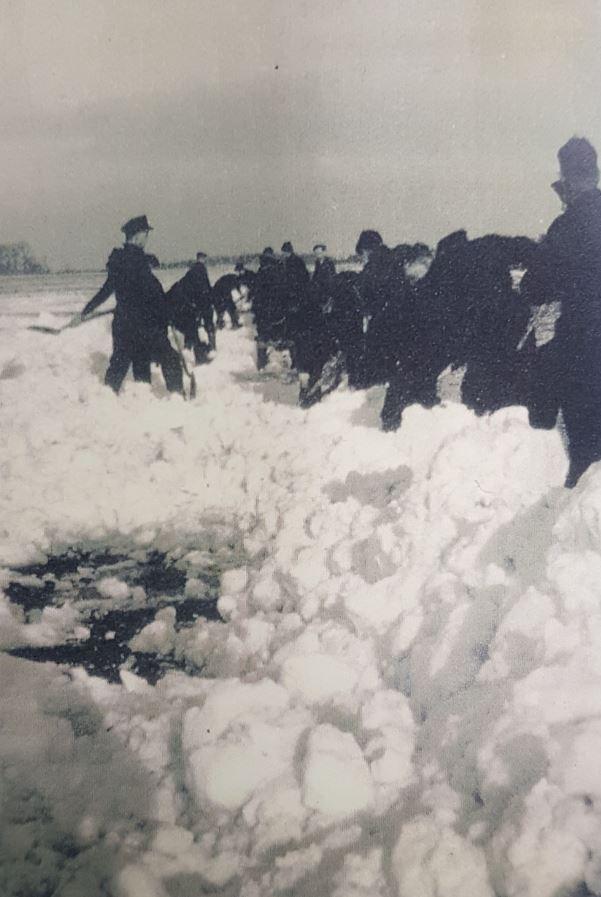

Clearing snow off the runway, Moreton-in-Marsh, 1944. Photo: Courtesy Dr Edward Fleming

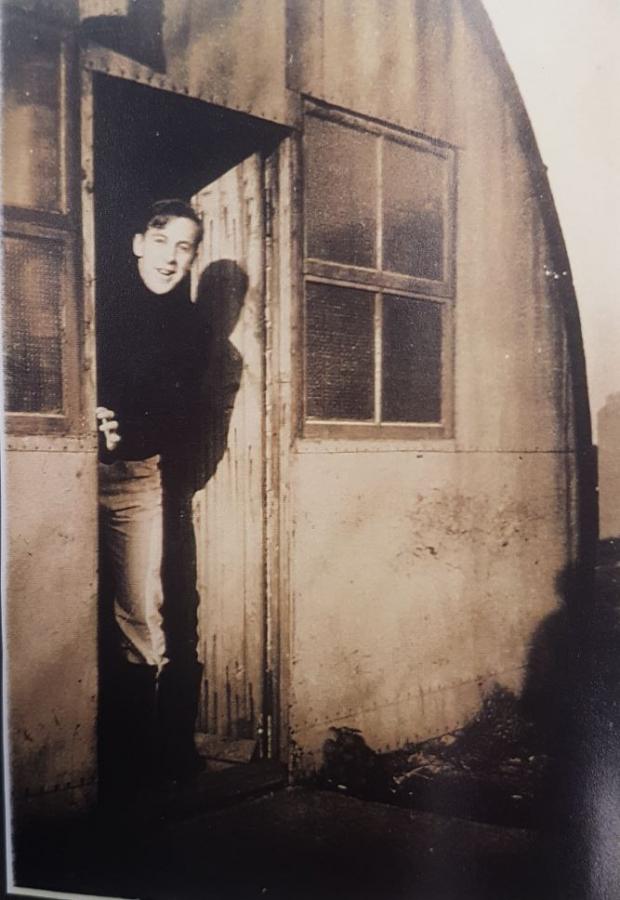

Edward Fleming in England during the war. Photo: Dr Edward Fleming

He spent 18 years working as a family history research volunteer at the Australian War Memorial, assisting visitors to discover records of family members who have served, before retiring on his 95th birthday. During his time at the Memorial, he participated in the indexing of the First World War nominal roll and compiled and published an index for the late Alan Storr’s 38 volumes of Second World War RAAF Fatalities. Most recently, he worked on the nominal and awards registers of the Malayan Emergency and Indonesian Confrontation.

He returned to Britain in 2017 to attend a commemoration for 550 Squadron, RAF, at its former base in Lincolnshire, and was invited to attend the official opening of the International Bomber Command Centre and Memorial Spire in Lincoln in 2018.

He is proud to be one of the “Odd Bods”, a collective of 25,000 RAAF personnel who served in almost 250 units under Allied military commands during the Second World War, including the Royal Air Force, Royal Canadian Air Force, Royal New Zealand Air Force and the South African Air Force. He was delighted to see the Odd Bods recognised in a plaque dedication ceremony at the Memorial earlier this year.

“It was an interesting time to live through … and I was very proud of my service in the air force … but I wouldn’t want to have another war,” Dr Fleming said.

“There are so many situations that I think of that could have gone so differently, but we got away with it, so we were very fortunate.

“They were really terribly serious things, and I’m very grateful.

“I’ve had a wonderful life since, and I can only say, I’ve been very, very lucky.”