'I did what I had to do'

John Ireland’s first mission was almost his last. “We’d gone over to do our first raid over the south of France at a place called Nance,” he said.

“We were quite happy with ourselves until we got shot by the German Messerschmitts.

“We were in an old Wellington and it was a beautiful old thing – it was a geodesic construction and was built like a Meccano set with only a skin over it – and the Messerschmitts came up, and ‘pow’.

“I had to say a couple of Hail Marys, but we got back alright, and we were a bit proud of ourselves.”

A formation of Wellington bombers during the war.

A flight sergeant in the Royal Australian Air Force during the Second World War, John had been posted to England as a 19 year old and was training as a wireless air gunner. He was selected to become a radio operator and flew 83 missions to the Continent as part of the Royal Air Force’s No. 575 squadron, one of dozens of squadrons under Transport Command.

Transport Command had been formed in 1942 to meet the changing conditions of the war, dropping paratroopers into battle and supplies to the front line, towing gliders, evacuating casualties to field hospitals, transporting troops, and providing other forms of crucial air support.

“You were like a taxi truck right behind the lines, and during those trips, we might land three or four times in paddocks to drop mail or supplies or pick up casualties,” he said.

“These fellows would groan and put out their hands as you walked amongst the stretchers on the plane. You’d see a hand come out and you’d hold it, and it would squeeze it, and the next minute it would be gone.”

John Ireland just before he left Australia. Photo: Courtesy John Ireland

He recalls being reduced to tears as he looked into the faces of the British prisoners of war and concentration camp survivors he picked up towards the end of the war.

“We had this one fellow,” he said. “He was in his late 30s or 40s, and he was looking out the side of the plane. At some stage, he asked, ‘Where are we?’ I looked at the map and I said, ‘That will be Dunkirk down there.’ He said, ‘It couldn’t be.’

“I assured him it was and showed him the map. He started shaking and he told me he’d been taken prisoner at Dunkirk five years earlier and that he’d worked his innards out from dawn to dusk on a farm. He said there were days when he’d look out across the water and he was sure he could see the coast of England …

“He couldn’t of course – it’s about 30 miles across, and you can’t see it; it was all in his imagination. He told me he didn’t know if his wife knew if he was alive or dead and that he had a couple of kids who were four and seven at the time.

“He was old enough to be my father, and I was just 20 years old. He started to cry and I put my head on his shoulder, and I said, ‘Come on, give me a cuddle,’ and this little nuggety bloke cuddled me and cuddled me. He cried like a child, and said he was sorry. He said, ‘Look what I’ve done to your collar,’ and I said, ‘Well there’s a dry one over here, try that one.’

“I can’t tell you how he got on at home – I’ve got no idea of his name, or number, whether his wife thought he was dead and had remarried, or whether his kids wanted to know him – but I’ve often wondered about him.”

John served on Dakotas with Transport Command during the war.

He remembers another incident involving a Dutchman and a German prisoner of war.

“The German couldn’t speak English, and had been badly wounded, so they covered him over with his coat a bit,” he said.

“As we were about to close the doors, one of the ground staff said to me, ‘Keep an eye on the Dutchman with the German … If the Dutchman gets wind of him, you’re going to have trouble.’

“He was a big, tough looking bloke … about 6 foot 3, and I duly kept my eye on him, but I had a lot on my hands with many badly wounded men.

“Suddenly, the Dutchman stood up and started making his way down to the back of the plane … We were seven or eight thousand feet up – nearly two miles up in the air – and we had 24 or 26 blokes in the plane. Some of them had never been in a plane before and they were frightened as hell, and then this happened.

England 1944. Wounded being unloaded from a Transport Command Dakota after being flown back from France.

“The Dutchman wanted to go down and belt this German up, so I told him to sit down, and he said, ‘Who’s going to stop me?’

“I had my pistol – my Smith and Weston – and I pulled it out. He said, ‘You wouldn’t be game,’ and I said, ‘Oh, mate, you’re talking to an Australian, and we’re mad.’

“I was responsible for all these people and I had a split second decision to make. I put it in his chest, and he went white and collapsed on the floor.

“I radioed ahead and the military police were there when we landed to escort him off the plane … I don’t know what happened to him, but the German guy was okay, and the others gave me the thumbs up as we were taking them off the plane.

“When I think on it now, I was just a young fellow with only a pistol to keep chaos at bay … Thank heavens things turned out as they did.”

British Gliders being towed by a Dakota aircraft over southern France.

A pannier being loaded onto a Dakota transport aircraft. The large wicker baskets were packed with food, arms, ammunition, wireless sets and spares of all kinds.

Another moment that would stay with him forever happened on New Years’ Day 1945.

“It started on 31 December 1944 when we headed to Brussels,” he said. “There must have been 100 planes on the tarmac, all lined up close together… Vickers Wellingtons, Spitfires, Mosquitoes, Harrow transports, B-25s, Avro Ansons, Austers, as well as the Dakotas.

“In the morning, on New Year’s Day, I headed out to the plane. I’d nearly reached it when I looked up and saw a formation of a dozen or more silver planes flying past low around the boundary.

“I said to one of the other blokes, ‘Gee, that’s a pretty sight.’ But even as the words left my mouth, my brain registered that they were the Germans. I turned around and started to run, trying to get back to the slit trenches near the hangars. The next minute they were shooting us up and one of the Focke-Wulfs lined me up.

“I could see him, and if I hadn’t put my head down, he would have taken it off; the cannons were going off beside me, and … within a few minutes, they’d shot the whole drome up.

“We had to go to Eindhoven, about 25 minutes away, and we had no guns, no parachutes, or anything – the only thing we had was pistols – and they said, ‘Keep your eyes open because there’s still a stray German Messerschmitt flying around; it could be looking for you blokes.’

A German Messerschmitt during the war.

German Focke Wulf FW 190A-3 refuelling during the war.

“I got up in the astrodome, but I couldn’t see him … and then it came over that we were clear to land. Just along the runway there was a crashed Messerschmitt, and I said to the boys, ‘We’d better go and have a look to see if this bloke’s alright.’ He was still warm, and I felt for a pulse, but I couldn’t get anything. It was a shock to realise that he’d only just been shot down; a few minutes earlier, he could have killed us, and now he was dead.

“When I pulled out his ID card, I saw that he was 21, just a year older than me … [and that] he’d been awarded the Iron Cross. I said to the other two, ‘Righto fellows, pop your head down, and recite the ‘Our Father’ over him; he’s someone’s son, the same as us, and I reckon he’s entitled to it – it will warm the track up for him as he goes to see the bloke upstairs.’

“I don’t know who that bloke was – I didn’t take his name or number – but I’ve thought about him for over 70 years.”

He has spent the past few years trying to identify the pilot and find his family. He knows just how easily it could have been him; the boy from Brunswick who first fell in love with aircraft as a child growing up in Melbourne.

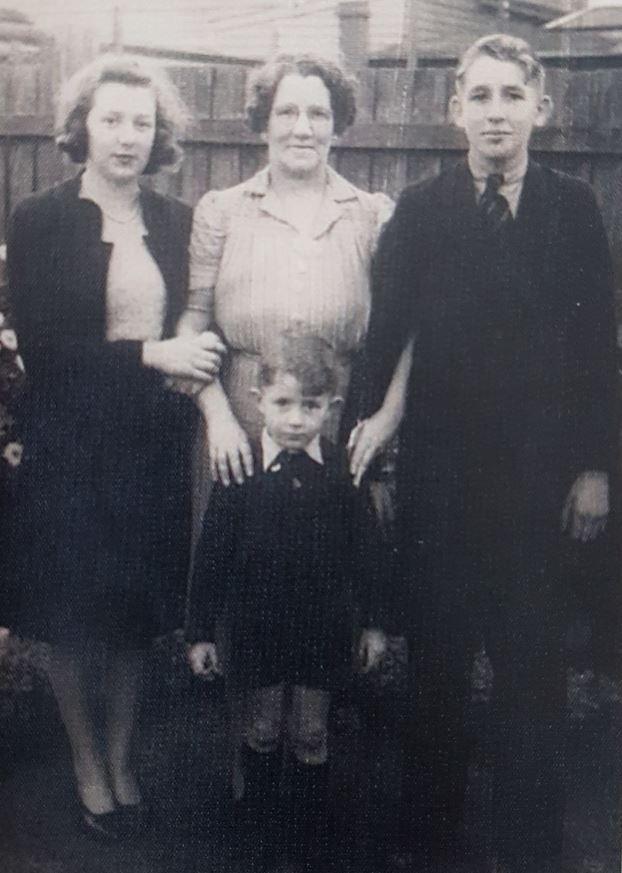

John with his mother, Stella, his sister Patricia, and his brother Barry in 1939-40. Photo: Courtesy John Ireland

“As a young nipper in Brunswick, we used to ride our bikes over to the Essendon aerodrome,” he said. “We loved having a sticky nose around the hangars, checking out all the planes… On a couple of occasions we were asked if we wanted to come up for a spin while they tested them... I would have been a boy of 12 or 13, and I never told my parents… but even just ten minutes in the air was a thrill for a boy… and I just got it in my blood.”

He was 14 years old when war came. Keen to do his bit, he joined the newly-established Air Training Corps at 16 and — with his parents’ permission — enlisted in the air force on his 18th birthday.

“My mother knew I’d made my mind up … and she didn’t stand in my way,” he said.

“I headed down to the RAAF recruitment building in Russell Street and lined up with hundreds of other new recruits. We were put through dozens of medical tests and aptitude tests. They were very strict, and not everyone got through in those early stages, so it was a relief when eventually I was chosen.”

He was called up for training on the first of January 1943, sailing for overseas service in November on SS Mount Vernon, an American troop carrier which had just brought thousands of Americans to Australia. He was surprised to see the tears in his father’s eyes as he said goodbye and shook his hand at Spencer Street Station.

“The Aussies stuck together like cream to a good parlour milk; and we did everything – unarmed combat courses, bivouacs,” he said. “The Poms couldn’t understand how we Australians could do it, and some didn’t even realise we could speak English.”

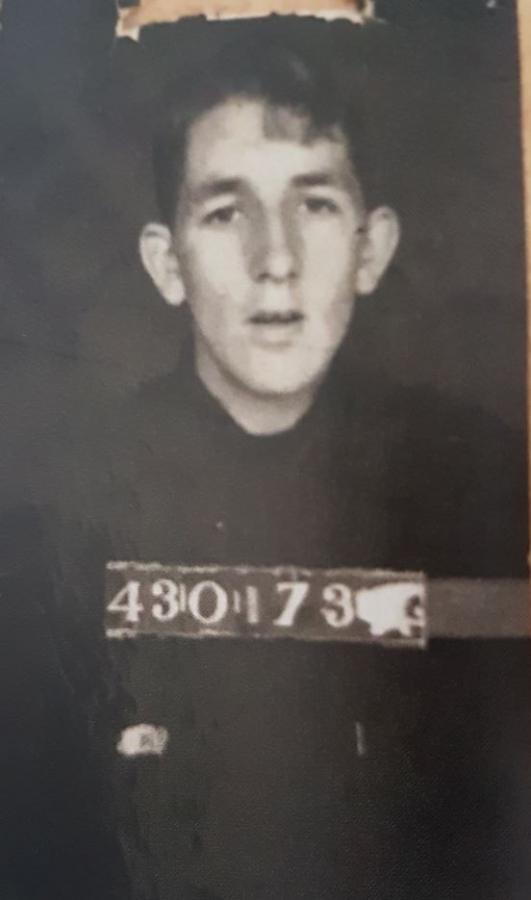

John Ireland just after he enlisted on his 18th birthday. Photo: Courtesy John Ireland

He recalls one course in particular; an unarmed combat course at Whitley Bay in the north of England.

“At the end of the course … we were divided into good guys and bad guys, before being left in a remote area for five days to fend for ourselves,” he said.

“I was a bad guy, and I paired up with my mate Don May. I remember the two of us looking at each other – muck all over our faces as part of our ‘bad guy’ look – and me saying, ‘Fancy putting up with this for five days; what are we gonna do?”

The answer arrived about 15 minutes later when an old truck came trundling along the road laden with hay.

“We weren’t supposed to take any money, but accidentally on purpose, I had put a 10 schilling note in my pocket,” John said. “When I offered it to the truck driver, his eyes nearly fell out of his head... We climbed in the back under the hay, and as we drove along we chatted to him. Suddenly, he told us to be quiet. Next thing he pulled over, and we heard voices; the ‘good guys’ asking him if he’d seen any strangers around.

“He said, ‘I saw a couple of black sheep in the paddock as I was driving along,’ but just as he started to take off, a couple of blokes came around to the wagon and began shoving bayonets into the hay. One went so close to my face, he could have poked my eye out.”

When they returned to Whitley Bay, they were hurled before their superiors and questioned about how they had returned so fast.

“We replied that we only needed to give our name, rank and number … When they threatened to charge us, I told them, ‘We’re Australians; you’ve got to get permission from Australia,’ which was nonsense, but they believed it.”

He thought he had gotten away with it, until a few years ago when he discovered he had acutally failed the course because he hadn’t “completed” it.

John, far left, with the boys, just outside their Nissen Hut after a swim. Photo: Courtesy John Ireland

John, far right, at Spencer Street Station just before he left Melbourne. Photo: Courtesy John Ireland

He went on to train on Wellington aircraft with Bomber Command and was selected for a conversion course, joining No. 575 Squadron in Transport Command in October 1944.

“They picked a pilot, a navigator and a radio operator and we got put on Dakota aircraft,” he said.

“The war was changing … and out of the blue four or five of us Aussies had to do a paratrooper course.

We had never heard of an air force like that where the air crew had to do a paratrooper course – that was for the army blokes – but they wanted us to know what it was like.

“When you have 22 paratroopers jump in your plane, someone in the crew has to be responsible that they are all geared up

“The men would sing as they jumped, and when the last man jumped, it would suddenly go quiet, and all you could hear was the motors going. It was the most eerie feeling. You would look out the door and see them, and they’d wave to you; some of them would be shot on the way down, and some of them would never get back …

“When the moment arrived for us to do our first jump, it was from a barrage balloon with a cable, 800 feet high. You’d sit there, and they’d say, ‘Ready, set, go,’ and then, ‘Bang,’ they’d hit you on the back, and push you out.

“You’re looking down thinking this is a bit of alright and then all of a sudden the ground is coming a bit fast at you, and you have to practise how to turn around and go with the wind and roll.

“It was marvellous, and gee I was proud of myself.”

Paratroopers on a training operation during the war.

Like many veterans though, John found his return to civilian life difficult.

“I did what I had to do, and I never spoke much about it,” he said. “Even when I came home, my parents didn’t ask what I did, and I never told them anything.

“I filed that chapter of my life away in my memory for safe keeping. I kept it all to myself: the happy and exciting, the deeply personal and sad. I simply found it too hard to convey what I had been through, and … did not care to open that chapter again.”

After 70 years of keeping his memories to himself, John began to tell his story, writing a book – A Blue Orchid Cook’s Tour: The War Memories of John Ireland – with the help of author Caroline Hutton.

“What motivated me above all was to tell the stories of friends who cannot tell them and to share the achievements and exploits of Transport Command,” he said.

“We were called ‘blue orchids’ when we came home – fancy pants – because we went over to England to ‘get away from the war’. As ‘blue orchids’ we were seen as having taken the easy way out, and scoring a ‘Cook’s tour’ of the world. No one heard or read about our experiences … Indeed, it was common to be told I had no right to be a member of the RSL as I hadn’t fought for my country.”

John Ireland at the unveiling of the Oddbods plaque dedication at the Australian War Memorial.

He helped form the Oddbods UK Association for those who had served with the RAF in England, and in 2016 was awarded the Légion d’honneur in recognition of his services during the war.

Today, he still feels lucky to have survived. He remembers watching a BBC documentary series – War in the Air – and realising how close he had come to not making it home.

“I thought look at the poor blighter; it’s a wonder they didn’t get knocked out – lucky I wasn’t there … and about a week later, I pulled out my log book, and sure enough, that was the plane I was in; how we ever got away from the things like that I don’t know.”

A few years ago, he heard a refurbished Dakota flying over Queenscliff in Victoria, triggering an avalanche of memories and emotions.

“For one moment, I guess the sound took me somewhere else – to another time and place, a long time ago.”