'I thought, I'm gone this time'

One minute Leo Inglis was keeping an eye on Japanese planes flying overhead, the next he was buried alive, fighting for his life.

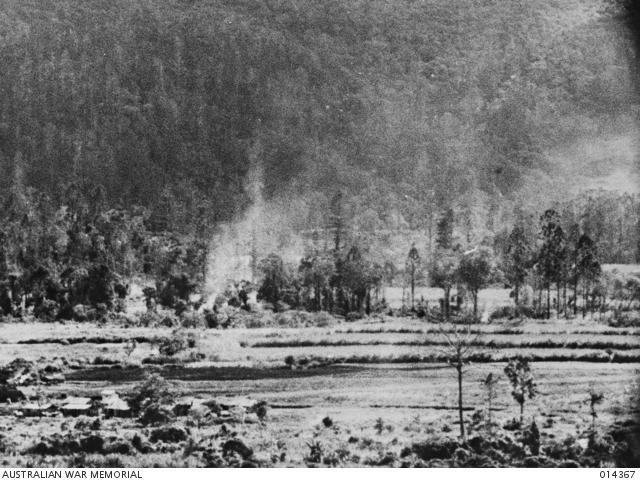

“Wau is only a small place, and over came these aeroplanes, these bombers,” he said.

“There must have been about 30 of them, and I was at headquarters up at the top of the airstrip. I saw them coming and I jumped into the fox hole.

“I thought, ‘I’m gone this time,’ and the bomb landed right on the corner of my trench, about six inches off it.

“I was on my hands and knees in the trench and it collapsed in on top of me and buried me. I was completely covered, and the other boys dug me out.

“I got a bit of concussion off the bomb too because it bounced me against the side of the trench where there were little rocks sticking out.

“It damaged my ribs, and just about knocked me out too, and I ended up in hospital for about three weeks.”

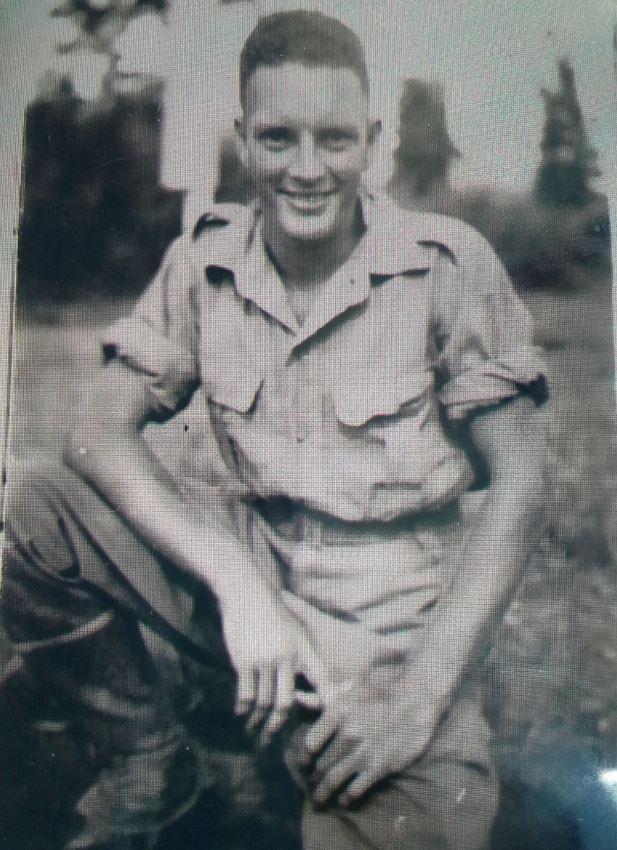

Leo and his twin brother Lionel during the war. Photo: Courtesy Leo Inglis

Leo and his identical twin Lionel were serving in the same unit in New Guinea during the Second World War. They had made a pact never to get into the same trench. When the Japanese air raids began, they would separate so that they wouldn’t be killed together. They were thinking of their mother at home in Sydney.

The twins had taken part in the battle of Wau a few months earlier. The airstrip at Wau was considered vital to the Allies’ strategy of winning the remaining Japanese-held coastal positions and disrupting the enemy’s south-west operations. With the airfield under fire, the troops had gone straight into action.

“We were told we were going into action, but we all thought, ‘Oh, this is another false alarm,’” Leo said.

“Then as the plane was coming in to land at Wau, all I could see was shrapnel going through the plane.

“The plane was coming down to land, and the plane didn’t stop; they pushed all our gear out, and as it was turning, the Japanese were still firing at us.

“Ten men were wounded, and they took off back to Port Moresby.

New Guinea, March 1943: Transport planes flying across the mountains towards Wau.

Wau, April 1943: Salvaging this point five inch machine gun from an American plane, Sergeant Rowe (left) and Corporal Heartwell, improvised a support for it and used the gun as a light anti-aircraft weapon at Wau.

“That night the Japanese had the bottom half of the airstrip, and the Australians had the north – the top end.

“The air strip itself was no man’s land, and we had to get our guns, and get them out of the box, and check them all out.

“We were stationed at the top of the airfield, and that night we told we were going to go straight into action against the Japanese at the bottom of the airstrip.

“I thought, ‘This is it,’ so we all stood guard that night, and then in the morning, it was time to go. We went down as close as we could get to the Japanese in the bushes, and they started firing at us.

“There were eight machine-guns, and it took us about five minutes to set the guns up.

“Now just imagine, eight machine guns, a company of mortars, and one 25 pounder, and they all start firing at about seven o’clock in the morning. It’s not very quiet. If I was to talk to you, you couldn’t hear me; it was that loud.

Wau, 3 March 1943: 25 pounders were flown in and unloaded at Wau aerodrome. At this stage, the Japanese were only a short distance from the aerodrome. These guns were assembled and went straight into action.

Wau, 3 March 1943: 25 pounder guns flown into Wau, and manned by Australians, preparing to open fire on the Japanese positions at Wau aerodrome.

Wau, 3 March 1943: Allied 25 pounders burst on Japanese positions a short distance from the aerodrome at Wau.

“In four hours’ time, the guns were still firing, but we run out of water, and of course, they are water cooled guns, the machine-guns.

“We couldn’t get any water, so we were told to keep firing, and then the guns stopped, one by one, because the barrels got that hot that they bent a bit and the bullets wouldn’t go through. I’d estimate it was about 12 o’clock when we all stopped firing.

“We were told to fire straight ahead, [and then to keeping firing around] to the right, and not to come back because the commandos and the infantry boys went in from the left to mop up the Japanese that were still alive in the trenches …

“It was estimated a week later that there were 500 Japanese down there, dead.”

Leo had been called up three years earlier at the age of 19. He arrived in New Guinea in 1942 and served with the 55th Battalion.

“I was in E Company – the machine-gun company – and I went to Port Moresby and down to Milne Bay,” he said.

Leo Inglis during the war. Photo: Courtesy Leo Inglis

“I was only little, and I used to have to have a pack the same as a big fella to do the training, and the sergeant would say take your [other] hand away and my gun would go zhoop [and fall down].

“I’d say, ‘I haven’t got the strength; look at me skinny arms,’ and I'd talk back, so I had to go and see the medical officer. I said, 'I can’t drill with the rifle, it’s too heavy for me,' and he said, ‘Oh, well, we’ll exempt you,’ so I got exempted, and they made me a driver – the company driver – with a few others as well.

“I went down to the sergeant there to learn how to drive, and the first thing he said was come here, here’s your licence. I hadn’t even touched the car, and I got the licence before even driving. They took me out in a paddock, and this is in Port Moresby, and he says, ‘That’s the clutch, that’s the brake, and this is what you do,’ and then he just sits there. I said, ‘Are you going to drive,’ and he said, ‘No, you are.’

“I remember it going bump, bump, bump, at first, but I was driving all day, and by the afternoon I was not too bad.

“In about five years, I never ever drove a car, only trucks, and when I got discharged and bought myself a car I thought it was fantastic. The trucks had a plain gear box… and you had to rev hard when you were going up [through the gears], and every time you were going up a hill, you had to stop the truck and put it in first gear and take your foot away from the accelerator, and it would go down.”

Milne Bay, October 1942: A truck hopelessly bogged in the mud at Gili Gili on the shores of Milne Bay.

Milne Bay: October 1942: A bulldozer bogged in soft mud near Gili Gili on the shores of Milne Bay.

He arrived at Milne Bay in May 1942.

“There was no wharf, so we had to go down the side of the ship, and ended up on what you’d call rafts, and off on to the beach.

“I thought it was great because I was young.

“We had to work on the airstrips, and we had to dig our guns in on the beaches. There were six altogether – two [at one end], two in the middle, and two up on the other end.

“There were about 50 of us in my company, and we all got malaria because we only had short trousers, short sleeves, and no mosquito nets to sleep under.

“We left that day on the boat to go back to Port Moresby to hospital, and the next morning the Japs landed at our beach …

“For two months, the word was the Japs are on their way here to Milne Bay from the north … and that was [frightening] at first, but after a while, we said, ‘Oh yeah,’ and we didn’t think about it.

“We were on the boat between Milne Bay and Port Moresby when we got the news that the Japs had landed at Milne Bay, right on the spot where we were.

“A Queensland battalion had taken over, and we all went into hospital for three or four weeks.”

Milne Bay, September 1942: A P40 Kittyhawk taxies from the runway through palm trees towards the dispersal area.

Milne Bay, October 1942: A Hudson bomber taxiing on the muddy Gurney aistrip.

Milne Bay, October 1942: A Beaufort bomber sends up a spray of mud during take-off from Gurney airstrip.

In September 1942, Leo’s battalion was ordered to move forward to Owers’ Corner along the Kokoda Track. Its task was to guard and patrol the Goldie River Valley to stop the Japanese using it as an avenue of approach. The machine-gun company pushed on to Ilolo.

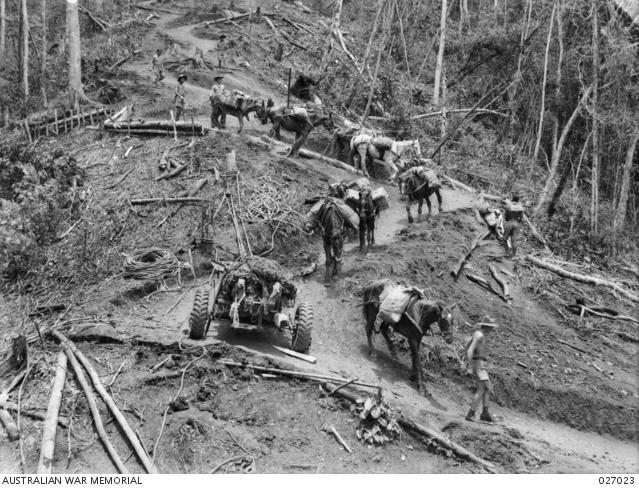

“We got back to our company, and we got sent up to the Kokoda Track,” he said. “They wanted machine gunners up there so as far as we got was where the two 25 pounders were. We had to help pull them into line with the thousands of men that were there, and the donkeys.”

In November 1942, the machine-gun companies from six infantry battalions – the 3rd, 36th, 39th, 49th, 53rd and 55th – were brought together to form the New Guinea Force Machine Gun Battalion. Renamed the 7th Machine Gun Battalion a month later, it undertook defensive duties around Port Moresby and Milne Bay before taking part in the defence of Wau airfield in early 1943.

Leo went on to serve on the Black Cat Trail, a rough overland track that ran from the coastal village of Salamaua into the mountains to Wau. Salamaua had been captured by the Japanese in March 1942 and converted into a major supply base. Men had to walk for several days to reach the forward area before taking part in the fighting or supporting the troops engaging the Japanese.

October 1942: Men leading pack horses and mules loaded with supplies into the Uberi Valley over which troops and supplies were taken to forward positions in the Owen Stanley Ranges. In the foreground is a 25-pounder gun that is being hauled through the valley to Imita Ridge.

September 1942: 25 pounder guns being pulled through dense jungle in the vicinity of Uberi on the Kokoda Trail.

“When I was on the Black Cat Track, and I went forward, I didn’t take my boots off for a week and my feet were all shriveled up,” Leo said.

“I was walking along up to the first stage, and I fell over in the mud. I was that tired, and it was hot too, and two officers were behind me. The boys I was walking with were going to pull me out, but these two officers pulled me out.

“I had mud all over me, and one of them took my rifle, while the other took my webbing equipment. They were majors, or something like that, up in that bracket, and when we got to our destination, I said, ‘There’s my men over there.’ They said, ‘No come with us,’ so I had to go with them to the officers’ quarters. I was terrified; I thought I was going to get in trouble, and so at that time I wasn’t too happy to go with them.

“They told me to strip off, and they gave my clothes to a native, and put a blanket around me. The next morning when I got my clothes back, they had been washed and were perfectly creased.”

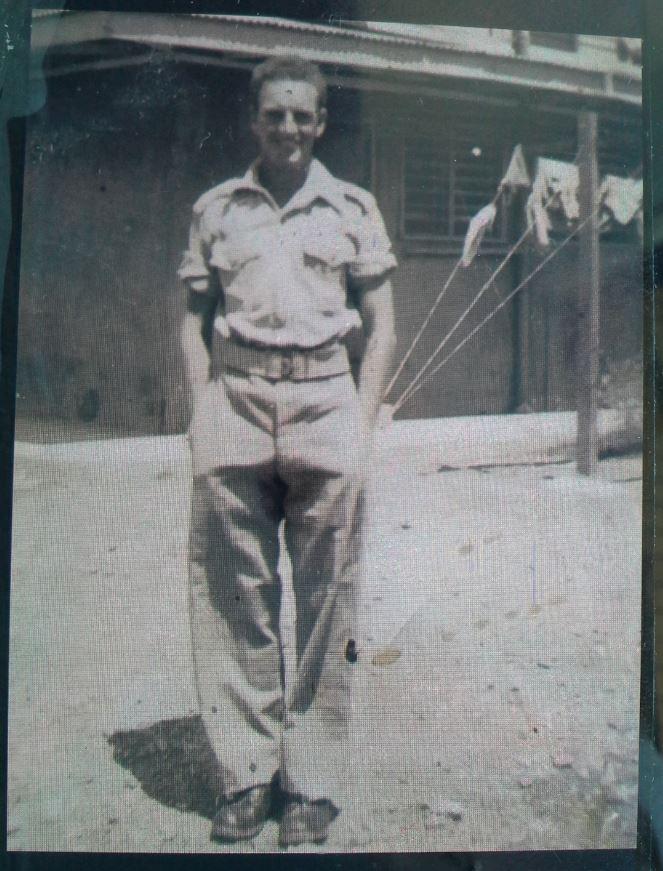

Leo Inglis during the war. Photo: Courtesy Leo Inglis

He couldn’t believe it when he was sent to the officers’ mess to have his breakfast before rejoining his unit.

“In comes my officer, and he blows me up because I’m eating at the officers’ mess. He made me stand up, and the other officers who were eating there were laughing. I saw the two who had helped me over near the door and I said, ‘Go and see those two fellows. They brought me in here,’ so he goes over, and he salutes them, and he immediately he turned around and went out.

“I don’t know what they said to him; and I wasn’t going to ask. He was too cranky. I couldn’t talk to him.

“And then when I got back to me boys, what do you think they saw? They saw me with my clean shirt, perfectly creased, while they still had sweat and mud on them. They didn’t let me live it down for about six months after that.”

He had just arrived at the next stage of the track when he fell over again.

“I said to the boys, ‘You haven’t dug in,’ and they said no, they weren’t going to because we had to move again later. And then about two hours later, I fainted again … I had malaria.”

Refusing help, he walked back to Wau by himself, and was admitted to hospital again.

Leo and Lionel with fellow soldiers in New Guinea. Photo: Courtesy Leo Inglis

He returned to Australia on leave in 1943, and married his wife Edna.

“I met her before the war, and we used to be great mates, and we started writing letters, and she wrote one letter saying we should get married, and that it could be arranged for when I came home, and I just said, okay.

“So I came home, and we got married, and I went back, and ended up in Borneo, and didn’t come home for another three years.”

He and his brother were in Borneo when the war ended. Lionel went on to serve with the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan, while Leo returned to Australia, sailing to Townsville in 1946, and then travelling by train to Sydney.

“When we got off at Central, these two girls were walking towards me, and I didn’t know which one was my wife,” he said, laughing. “I hadn’t seen her for three and a half years.”

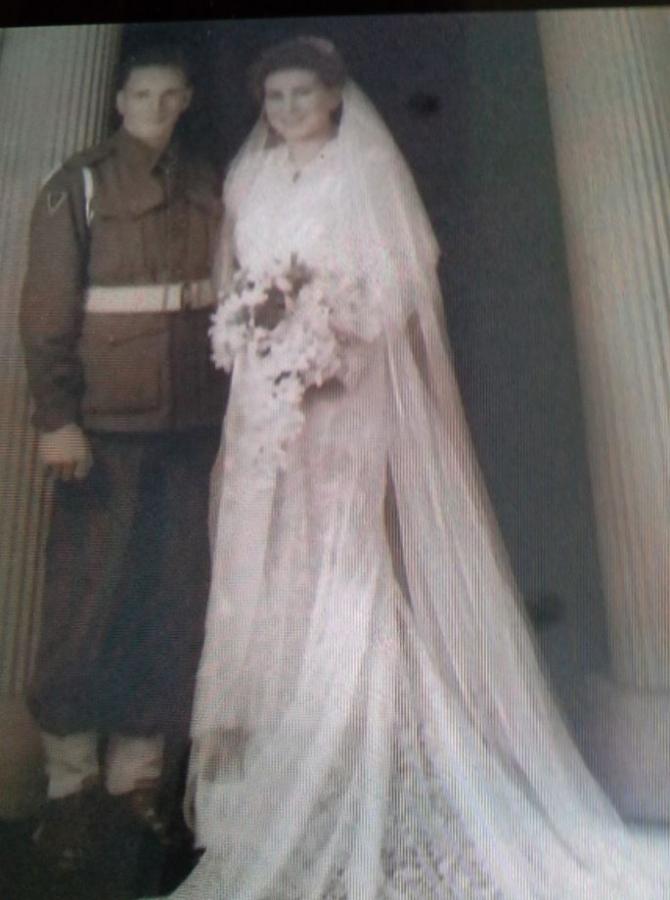

Leo Inglis with his wife Edna on their wedding day. They were married while he was on leave. Photo: Courtesy Leo Inglis

Leo and his wife had four children – one girl and three boys – and 12 grandchildren. He moved to Kiama in his retirement years and would visit the Australian War Memorial in Canberra every few years to pay his respects and remember his mates.

Mateship meant everything to him during the war.

“It sure did,” he said. “Without them, you would have been gone.”

He laughs when he tells how one of his best mates would check the spelling in his letters to make sure that everything was correct. He gave Leo a dictionary during the war with a little inscription. “I’ve still got that dictionary,” he said, laughing again. “It’s very battered, and torn, but I’ve still got it. A couple of times, he wrote the letter for me, so he wrote to my wife, and one time when he got leave, and I didn’t, he went and saw her, and I joked, ‘You’re pinching my wife off me!”

Like many veterans, Leo didn’t talk about the war afterwards, preferring to remember the funnier times. He didn’t take part in his first Anzac Day march until he was 60.

“I was young, and I didn’t think about it [at the time],” he said. “I was [frightened] at first, but you try not to show it to the other boys, to your mates.

“I still have bad memories, if I think about it long enough …

“But, yeah, I was lucky.”

Leo Inglis passed away earlier this year.