A Mother's Love

Finely engraved on the reverse side of this gold and glass brooch are the words "To dear John Freeth’s Mother, With regard from his friends at Angus & Coote. 1944." At the centre of the brooch a hand-painted portrait of the youthful Flight Sergeant John Samuel Freeth in uniform sits under the protective glass.

Sweetheart jewellery of this period was typically worn by a mother, wife or girlfriend as a public display of pride and badge of honour during their loved ones service. However, unlike most sweetheart jewellery, this brooch was presented to Mrs Ethel Annie Freeth almost a year after her son died. It was given to her by his friends at Angus & Coote to help her come to terms with her son’s death.

John had worked as a jewellery salesman at Angus & Coote in Sydney before he enlisted with the Royal Australian Air Force on 25 May 1941. A single man of 21 years, he listed his mother, Ethel, as his next of kin. After training as a pilot in Australia and Canada, he was posted to the UK in late 1942, and joined 455 Squadron RAAF from mid-January 1943 in Scotland.

Photograph of Aircraftman John Samuel Freeth and his mother, Ethel, in a city street in Sydney, c1942. Taken before John left for Canada with the Empire Air Training Scheme on September 1942. P02450.002

Equipped with Handley Page Hampden torpedo bombers, 455 Squadron flew anti-U-boat patrols with RAF Coastal Command over the Norwegian Sea from Shetland. It didn’t take long for John to distinguish himself. In late April 1943 he piloted a Hampden aircraft from 50-80 feet, attacked and sunk the German U-boat 227 off the Norwegian coast with depth charges, although he and his crew were untrained in anti-submarine attack. During the attack they were hit by machine gun fire, but took no casualties. However, his luck did not last.

On 24 May 1943 in a non-operational exercise flight over the sea off Fraser Borough, Scotland, John’s Hampden aircraft collided in the air with Bristol Beaufighter JL502 of 235 Squadron. John and his crew were instantly killed, but because of the nature of the crash, only two bodies were recovered from the sea: Sergeants Downing and Wheatcroft. John and the fourth crew member were never found.

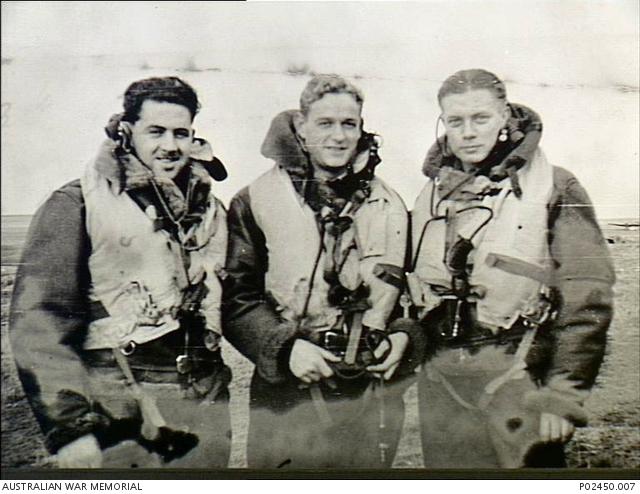

Turnberrry, Scotland, December 1942. Left to right: Bert Downing, John Freeth, Bert Wheatcroft. P02450.007

Almost two years to the day he enlisted, John was reported missing, and then later presumed dead. Home in Australia this accident had ongoing consequences for John’s mother. In the absence of a body, Ethel continued to believe that her son was alive. It was not uncommon for mothers or family who had no tangible proof of the death of a loved one to hold out hope. A statement in John’s repatriation file describes:

The evidence that F/SGT Freeth lost his life in an aircraft accident in the U.K. in May 1943 is conclusive, but Mrs. Freeth is one of the numerous mothers who will not accept evidence, and she has since 1946 approached the former Prime Minister and the Minister for Air on the matter.

Ethel was convinced that John had survived the aircraft crash and was suffering from severe memory loss in a hospital in the UK or Australia. She was further convinced when in December 1946 she saw an article printed in Sydney's Daily Mirror about two RAAF pilots who had broken a trans-Tasman record by flying a Mosquito aircraft from Mascot, Australia, to Auckland, New Zealand. Ethel mistook one of the pilots, Flight Lieutenant Leonard Lobb, for her son. She continued to make enquiries about the pilot with fair features.

In one of the last-minute sheets made by the Department of Air for John’s repatriation file in 1950, we see a picture of a mother who refused to give up on her son:

Mrs. Freeth called again. She is still of the opinion that her son is alive. I explained the details of the crash and endeavoured to convince her that there could be no doubt that her son was killed and that it was impossible that he had taken part in a flight in 1946 under the name of Flight Lieutenant Lobb. She remained unconvinced but did not ask for any action to be taken and departed saying that God in his own good time would reveal the true facts.

We don’t know if Ethel had come to terms with her son’s death when she died in Sydney in 1971.

While this memorial brooch may have provided some comfort to Ethel, it does not appear to have deterred her efforts to find her son. This Mother's Day, remember the mothers, like Ethel Freeth, who have lost loved ones in war.