'I look at my arm, and I miss the military every day'

When David Nicolson served in a remote outpost in Afghanistan’s Mirabad Valley in 2011, there was a standing joke that “Mates don’t let mates drive Route Whale”.

The rough road was Taliban territory and a major insurgent corridor. There were so many improvised explosive devices that it was rare for a convoy to make it home without finding one – or being hit.

“Commandos keep referring to Mirabad Valley as Mira-bad-arse Valley – and it was – but we called it ‘IED Valley’,” he said. “The biggest threat for us was IEDs, and obviously getting shot at, but Route Whale was our route, and it was our only route through the valley … I hit four IEDs all up … and the Americans got hit so often that they carried a flat-bed truck with them.”

An armored vehicle driver and crew commander with B Squadron, 3/4 Cavalry Regiment, David had deployed to Afghanistan in June 2011 as part of Combat Team Alpha from the Royal Australian Regiment’s 2nd Battalion during Operation Slipper.

The combat team was part of Australia’s Mentoring Task Force 3, helping train members of the Afghan National Army, which was tasked with blocking the flow of weapons and supplies to Taliban fighters.

David remembers one afternoon when he and his fellow soldiers, tired after a full day of patrolling, climbed aboard their Bushmaster armoured vehicles and headed off to complete one more task before returning to their patrol base. They passed through a small village that was normally full of people, but this time there was no one in sight.

“Usually there are kids and they wave, but there was nobody,” he said. “Straight away we’re like, ‘Nobody’s here; something’s going to happen, keep your eyes open,’ and then I looked up one of the alley ways, and this kid was pushing all of his sheep into one of the houses.

“The next thing there was a Molotov cocktail thrown at the rear vehicle – we had no idea where it came from – and then the radio started chirping up. So we were like, ‘Okay, something’s going to happen,’ and the engineer who was in the left seat, said, ‘Stuff it, let’s go.’

“We were coming up to the house that we were meant to stop at, and we would have been about 10 metres from where we were meant to turn, and there was one in the wall.

“It was a directional force charge, and … it went off into the side of the vehicle and pushed it quite a bit.”

The massive blast lifted the 15-tonne lead vehicle onto two wheels, where it paused before slamming back onto the ground. It was the second time David had been in a vehicle hit by an IED.

“It was like a tube – and they use old artillery shells as well – and they just pack it with explosives, and ball-bearings and nails and all sorts of stuff,” he said.

“It’s really loud, but it’s more of a ‘whoomp’ sort of noise, and then it’s just black for maybe two seconds, and you are just covered in dust; dust is everywhere, and in your eyes, nose and mouth you have that smell and taste of explosives.

“I looked to my right, and my whole window was just peppered, and there big spiderweb [cracks] everywhere because of all the stuff hitting the window …

“Your adrenaline goes into overdrive, and later, after the adrenaline drops off, you feel sick … you get thumping headaches … and you spew.

“While your body is going through all of this, your training kicks in and you’re making sure that you’re okay, and that the boys in the back are okay and casualty and damage reports are going out.

“You’re setting up security, and eyeballing the area for signs that it’s a complex ambush, for signs of the enemy, the triggerman and lookouts.

“The front wheels were pretty shredded, and the bin and stuff on the Bushmaster were peppered with big holes – one of them I could fit my fist in to it – so we were like: ‘We’ve just had a Molotov cocktail thrown at us, we’ve just been blown up – we’ve got to get out of here.’

“It took us ages because the steering was wrecked and the wheels were all stuffed, but it’s a tough vehicle, so it could still go, and we hobbled away up on top of the hill and we got it back.

“It’s just one of those things. It was just a split-second decision – ‘Let’s rocket run, let’s just get back’ – so [we] were very lucky; and it was a good day for us, a very good day.”

Before he completed his nine-month posting, David hit two more IEDs and witnessed countless more incidents. He survived them, too.

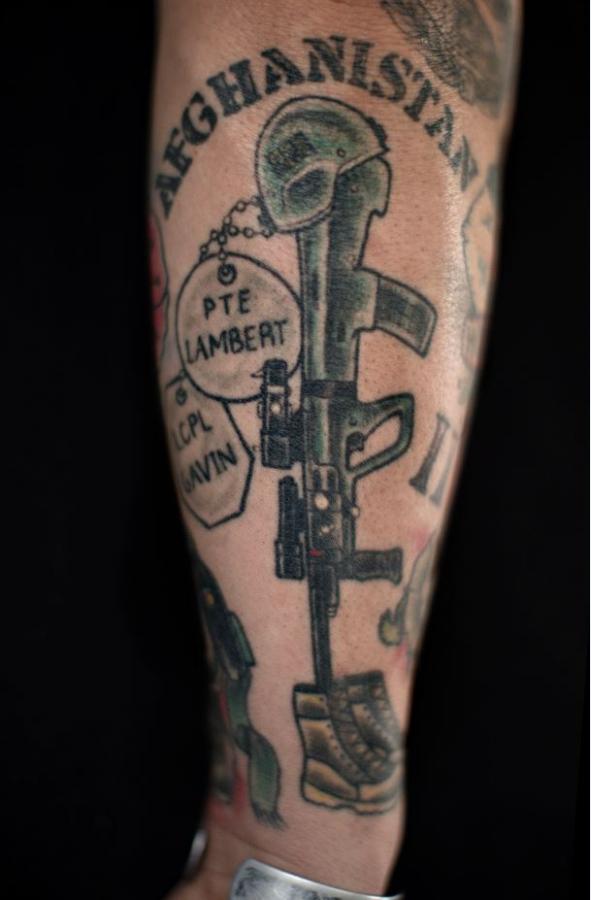

Today, he has an image of the Bushmaster tattooed on his arm, a permanent reminder of his experiences in Afghanistan.

His story is told at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra as part of Ink in the Lines, a new temporary exhibition sharing stories of Australia’s military veterans, through their tattoos.

The exhibition is the first of its kind at the Memorial, and features personal stories from men and women who have served with the Army, Air Force and Navy in conflicts and peacekeeping operations from Iraq and Afghanistan to Rwanda and Somalia.

“My tattoos are the old ‘Sailor Jerry’ style tattoos,” David said. “I wanted them to tell a story of the things I’ve done, and the places I’ve been. It’s a reminder every day.”

A Soldiers’ Cross, and the Ace of Spades speak of loss and luck, while Mirabad Valley is where it all happened.

“I was lucky,” David said. “The Ace of Spades is the ‘Death Card’, but it’s also got the A for Alpha Company, with the two for 2RAR.

“But the ‘Death Card’ is not only for the four IEDs that I hit, it’s for the luck that everyone had.

“We had a ridiculous amount of luck; we had guys tripping trip wires – didn’t go off; guys getting trip wires round their leg – didn’t go off; guys stepping on IEDs – didn’t go off; vehicles completely destroyed, but people survived, and there are loads of stories like that.

“A lot of boys had really close calls; we had a guy shot in the neck – again, a little bit to the left, a little bit to the right, and it could have killed him. It was just endless – but it was the same in every company.

“I know a guy who got hit in the back of the head, but the round that hit his helmet hit the weights at the back of his night-vision goggles, and I know loads of guys in Special Forces cruising around with holes in their pants.

“I don’t know how we got so lucky over there, but for some reason, we had a massive amount of luck. There’s just little things that you happen to do – like ‘stuff it, let’s rocket run’ – and it’s those little things that can change the whole thing, so that’s the reason for the ‘Death Card’ – beat it.”

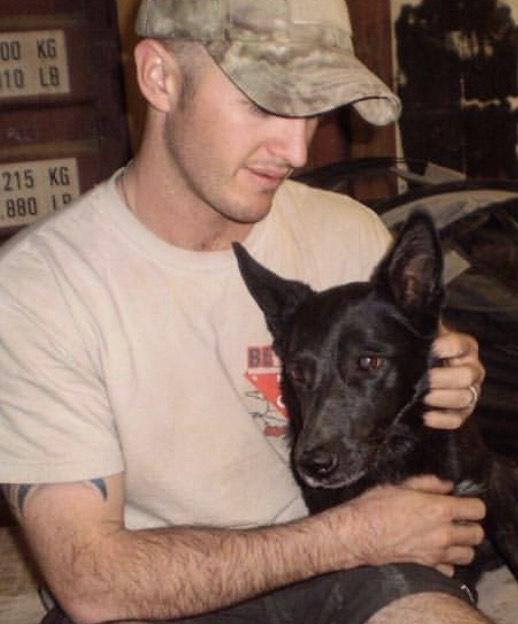

A portrait of much-loved explosives detection dog Flojo reflects the bond between military working dogs and the soldiers whose lives they help to save.

“She was a little life saver and she was a huge part of my deployment,” he said.

“She found loads of IEDs, weapons caches – everything – and every time we went out, she would find one.

“If she wasn’t working, she just wanted a cuddle, and she was that little piece of home for everyone.

“She sadly passed away in 2013 of cancer … but she was a little sweetheart, and everybody loved her.

“She was always there for a cuddle, and just seeing her do her work perked everyone up.”

A portrait of Popeye the sailor and a turtle crossing the line represents the four years he served in the Royal Australian Navy before transferring to the Australian Regular Army in March 2010.

“My whole family is military,” he said. “My dad’s army, my uncle’s army, my godfather – everyone’s army … and growing up, I always wanted to be in the military.”

He served in the navy as a boson’s mate and on patrol boats in Darwin during Operation Resolute. When he transferred to the army, his family and friends joked that he had “finally seen the light” and the “green blood” had come through. He thought about becoming an engineer, but then decided on a cavalry regiment.

“When I was in Darwin, I saw a ‘Bushy’, and it was big ugly beast, and I loved it,” he said.

“Then a warrant officer came in, and he said, ‘3rd Brigade are deploying, and they need soldiers up there with B Squadron with the Bushmasters,’ so I stuck my hand up in the air as fast as I could.

“Being lead vehicle, I was basically the proving vehicle for the rest of them. You’re looking out for IEDs, but you’re proving the road for everyone behind you, and when they said you get a dog, I was like done. I’ll be lead vehicle, no problem.

“I have a huge amount of respect for engineers and for the infantry … The most stressful part was watching your mates lying over the top of IEDs brushing dirt away …

“They were unbelievable, and I can’t imagine how stressful it was for them. The amount of IEDs those guys found was amazing, and yet they were always smiling.”

To have their story told at the Memorial means the world to him.

“I look at my arm, and I miss the military every day,” he said. “That’s all I wanted to do and I have no regrets. It’s a massive, important part of our lives … so to have your story and your brotherhood here is unreal. This is a place vets can come, and they can tell people – their family, their friends – this is what happened, and this is why.”

Ink in the Lines is now on display. Visit here.