The fact Ted hung on and was able to survive is just amazing

Ted Buerckner. Photo: Department of Defence photographer, NAA: B883, VX23638

Ted Buerckner spent three days in the middle of the ocean, clinging to a makeshift raft as the men around him died one by one and vanished beneath the waves.

He had already survived the horrors of the Thai-Burma Railway, and now he was fighting for his survival again after the sinking of the Japanese transport ship, Rakuyo Maru, in September 1944.

Exposed to the elements and coated in oil, he was one of 280 prisoners of war who were later found and rescued after the sinking.

His story of survival is told at the Australian War Memorial as part of Against all odds, a special temporary exhibition featuring personal stories of escape and endurance from the First World War to Afghanistan.

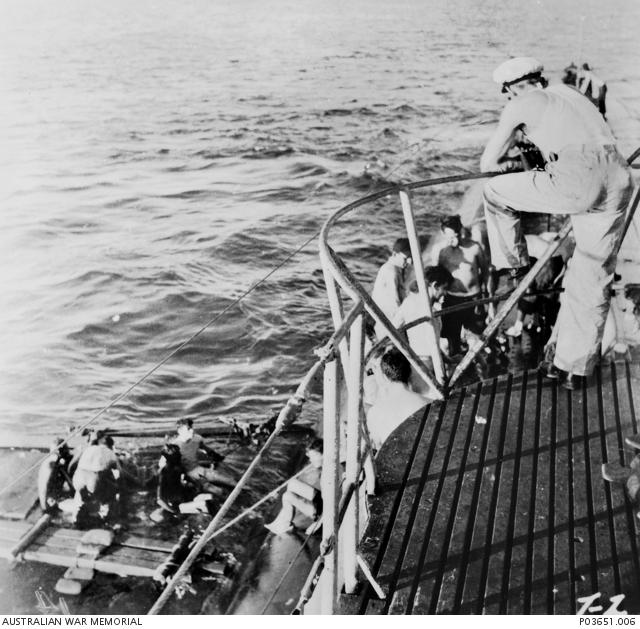

Two Australian survivors are rescued from the sea by crew members of the submarine USS Pampanito.

Oil soaked British and Australian prisoners who survived the sinking of the Japanese transport ship Rakuyo Maru on board the submarine USS Sealion.

Curator Dianne Rutherford said Ted’s story was a remarkable one.

“This exhibition is about ordinary people doing extraordinary things,” Rutherford said. “Some stories are over in a few minutes, while others drag on for weeks, but they are all amazing stories of how courage, determination, and sometimes a little bit of luck can be all that stands between a person and death, wounding, or capture…

“The fact that Ted survived after all that he had been through is amazing.”

Private Edward Buerckner had served with the 2/2nd Pioneers in the Middle East and was taken prisoner in Java in March 1942.

He was forced to work on the Thai–Burma Railway and survived more than two years of harsh imprisonment at the hands of his Japanese captors, suffering slave labour, rampant disease and a starvation diet.

British and Australian survivors on board the submarine USS Sealion.

In 1944, he was one of more than 1,300 British and Australian prisoners crammed aboard the unmarked Japanese transport ship, Rakuyo Maru, when it was torpedoed and sunk by the American submarine, USS Sealion, in the Luzon Strait on 12 September.

Japanese ships rescued the Japanese survivors, but the prisoners were forced to fend for themselves alone in the ocean.

“For two years they’d basically been on a starvation diet, and worked nearly to death in unbelievably poor conditions,” Rutherford said. “They were being transported to Japan for more of the same when the Rakuyo Maru was hit, and then they were just left there alone in the water.

“But the ship actually took a while to sink, so some of the men went back to try and get supplies or to break up pieces to make rafts out the debris.”

British and Australian prisoners of war who survived the sinking being picked up three days later.

A group of 130 prisoners were rescued by a Japanese ship a few days later, re-entering captivity, but those who remained in the water were left to fend for themselves once more. Already in an emaciated condition, many succumbed to illness or delirium.

“The fact that any of them survived is amazing,” Rutherford said. “Ted and the other survivors tried to band together in small groups, but some of the men were suffering from malaria, and some started drinking seawater as well.

“Ted ended up in a group of about 40 men on a dozen rafts that had been tied together, but there was no water, no food, and some of the men started to become delirious.

“In one of Ted’s accounts, he tells how he saw one prisoner pretty much go insane and drown another prisoner ... So, each day that he’s in the water, he’s watching more and more men die, or just vanish into the waves around them.”

Survivors formed groups and fashioned makeshift rafts from what floating debris was available to them.

Then, shortly before sunset on 15 September, the submarine USS Pampanito discovered the survivors and called for help to rescue them.

“At first the Americans thought the men were Japanese, but then they realised they were Australian and British,” Rutherford said. “They were as thin as rakes, covered in oil, and had been exposed to the elements in really dreadful conditions.

“Ted was lucky; he was found and rescued by the USS Sealion – the submarine that sank them – along with 53 others who were cleaned, treated, and fed before being taken to the island of Saipan [in the Western Pacific].

Two survivors are rescued from the sea after clinging to a makeshift raft for several days.

“But the submarines couldn’t rescue everyone because of the threat of Japanese vessels in the area, and the fact that the subs just didn’t have the room.

“They could only take so many men, so the Sealion had to leave, but they could hear other prisoners yelling, and they had to leave them behind.

“One man who had seen the Sealion and the Pampanito but hadn’t been able to get their attention, made the comment: ‘I wasn’t angry, just disappointed.’

“He was rescued two days later, but just imagine; you’re in the middle of nowhere; you’re in the middle of the ocean, not knowing if any other ship will come anywhere near.”

Australian prisoners of war are rescued by the crew of the submarine USS Pampanito.

By 17 September, more than 150 men had been rescued by American submarines before a cyclone halted further searches.

“But it wasn’t the end for the survivors,” Rutherford said. “They were interrogated about what was going on, who they saw, where they saw them, and how they died. That’s really where we first find out about the Thai–Burma Railway and the treatment by the Japanese.

“A few of the survivors actually died on board the Sealion, but Ted survived and eventually returned to Australia, where he suffered from recurring bouts of malaria before being discharged in July 1945.

“It was really difficult for the men when they got home. They had the Eighth Division patches on their uniforms, and when people saw them in the street they stopped them and asked them questions. Because everyone wanted to know what had happened to their family members.”

Crew members of the submarine USS Pampanito gather on deck.

Ted’s family knew exactly how they felt. His brother Charles was also a prisoner of the Japanese. He had been told that Ted died during the sinking of the Rakuyo Maru and only learnt of his brother’s survival when he was liberated a year later.

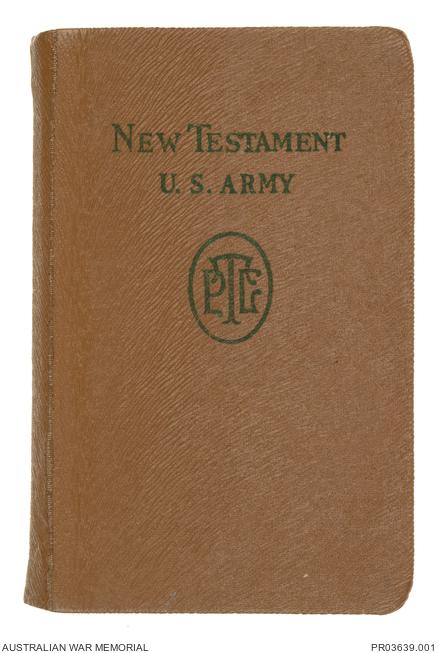

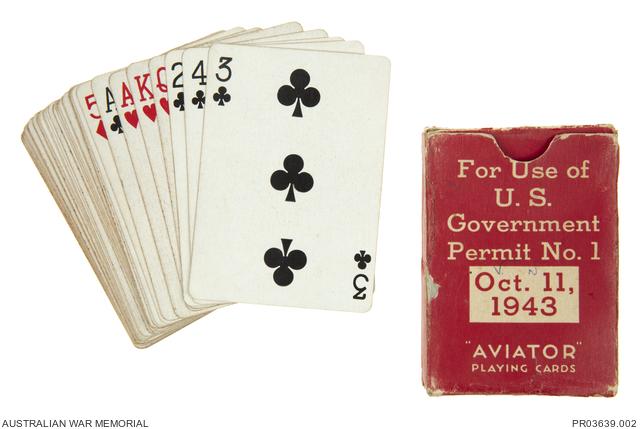

“The fact that men like Ted still hung on and were able to survive in those circumstances is just amazing,” Rutherford said. “When they were found, the survivors had absolutely nothing; some of the men were naked, some might have had shorts, or some scraps of clothing. But really, they’ve got nothing. The men on the Sealion looked after them and gave them some things.

“Ted ended up with a little New Testament and a pack of American Red Cross playing cards – and he kept them for the rest of his life.”

Today, more than 75 years after the sinking of the Rakuyo Maru, the objects are on display as part of the temporary exhibition at the Memorial – a poignant reminder of one man’s fight for survival, against all odds.

Against all odds is on display in the mezzanine level of Anzac Hall until June 2020.