Remembering Alex Bidice

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people please be advised that the following article contains the names of deceased people.

Lyn Burke was researching First World War soldiers from Proserpine when she first came across the name, Private Alex Bidice.

He and his friend, William Fry, had enlisted together in Queensland, and were both killed in action during the fighting on the Western Front.

But while William Fry’s name was listed on the local cenotaph, Bidice’s was not.

“He and William Fry enlisted together in Townsville, but it was very, very, hard to get information about him,” Lyn, a local historian, said.

“If you look up the surname Bidice, you find no one, no one at all; there is not one person by that surname, so to me, it looked like he made it all up.

“There was nothing to be found – no birth records, no anything – which led me to think, for quite a number of years, that this young fellow might be Aboriginal.

“He and the Fry boy had pretty well identical answers on their enlistment papers. Where were you born? Proserpine. What’s your religion? Salvation Army. Things like that. So they were very, very similar.

“But who was this boy, Alexander Bidice?”

Determined his story should not be forgotten, Lyn spent years trying to learn more about him and whether he was one of the more than 1,200 Indigenous Australians who enlisted during the First World War.

Little did she know, the answer would lie in a letter written more than a century ago.

“We knew there was some connection with the Fry family, so we looked into the Fry family and their boy William,” she said.

“They owned a big cattle station, and it’s a well-known name in the area, still to this day. Their cattle stations are still being run by family members, but at that point in time, there was an Aboriginal mission nearby, which was run by the Lutheran church.

“It was next to a property owned by the Fry family, so we tried to go through that to find some information, but nope, we couldn’t find anything.

“He was Mr Elusive. There was no birth record. No nothing.

“I even tried the Salvation Army to see if we could delve into the past that way, but they couldn't help me with anything more.

“What we did know about him, and what we could pick up from his enlistment papers, was that he was educated.

“He could write, and he wrote quite fine, so we knew he had been to school somewhere.

“We even tried that avenue, and searched all the school records from back then, but it was a no go as well.

“It took many years of research, and then I got onto Michael Bell, the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Memorial.

“I sent him what I had on Bidice, and it took not even 24 hours for Michael to say, ‘Quick, ring me back.’

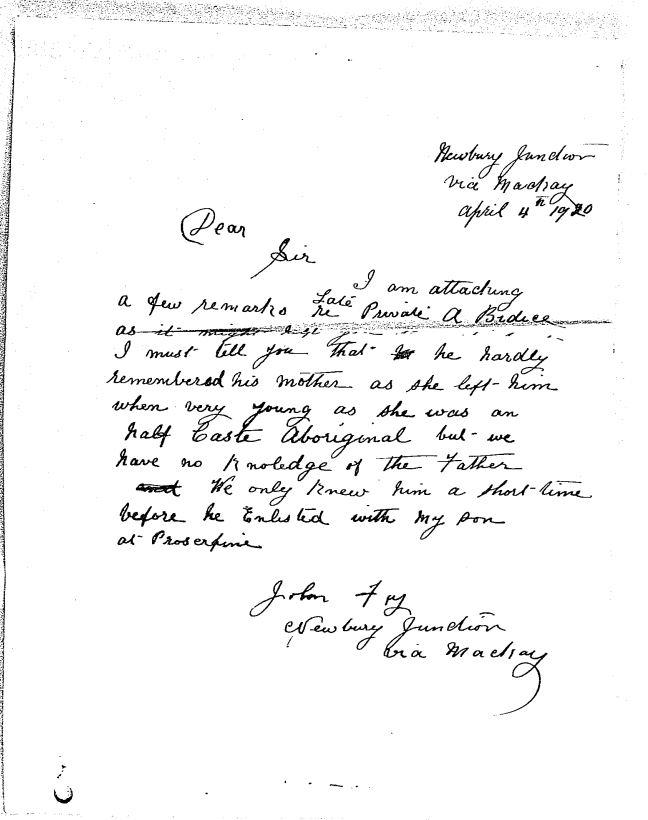

“He had found a letter and the form that the Fry family had filled out so that Bidice’s name would go up on the Roll of Honour at the Memorial.

“This letter was dated 1920, and it confirmed he was Aboriginal.”

Lyn had the answer she was looking for.

Alex Bidice was born near Proserpine on Queensland’s north coast around 1896, a member of the Gia and Ngaro people who reside in Queensland and the Whitsunday Islands.

He hardly knew his parents, and was working as a labourer when the First World War broke out.

He enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force on the 10th of December 1915, alongside his friend William Fry.

He was assigned to reinforcements for the 47th Battalion and embarked for overseas service from Sydney on board the troopship Hawkes Bay in April 1916.

He entered the trenches of the Western Front in July and his first major battle took place not long after, when his unit took up positions around the ruined village of Pozieres. It was widely regarded as a living hell by the troops who fought there.

Having survived the carnage of Pozieres and Mouquet Farm, Bidice would go on to endure the bitterly cold winter of 1916–17. Like many who suffered from the freezing, wet, cramped conditions at the front, Bidice began suffering from chilblains on both feet, which developed into trench foot. He was evacuated to England for treatment, and wrote to the Fry family from hospital to let them know he was “getting on alright”.

Bidice went on to serve in Belgium, and was wounded at Messines in June 1917. He was taken to a nearby casualty clearing station and treated for shell-shock, returning to his unit in time to take part in the attack at Passchendaele Ridge. He was killed at Passchendaele on 12 October 1917, aged 21.

He never saw William Fry again. Assigned to the 52nd Battalion, Fry had been killed in action at the battle of Messines Ridge.

Their bodies were never recovered, and today, their names are listed on the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing in Ypres, along with the names of more than 50,000 others who have no known grave.

More than a century after their deaths, Lyn travelled to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra to lay a wreath in their honour at a Last Post Ceremony commemorating Bidice’s life.

“I still get teary relaying his story,” she said.

“Basically, Bidice didn't really know anything about himself either, let alone me trying to find out about him 100 years later.

“So when I rang Michael, and Michael had the answer on the Aboriginal side of it, I cried …

“He needs to be known and he needs to be acknowledged.

“I even did little newspaper stories for the local paper on him and Fry to see if someone might know something. But there was nothing. And somehow his nothingness just got me. He needed more than nothing.”

Today, Alex Bidice’s name is listed on the local cenotaph at Proserpine, alongside that of his friend’s.

“Thank goodness for the Fry family,” Lyn said.

“He had no next-of-kin but John Fry, who was William Fry’s father. And in his will, he left everything to May Fry, his friend’s sister. The government at the time wouldn't give her anything, and up until the 1950s, she was still trying through a local solicitor's office to get his things back from the military … but to no avail.

“He must have meant quite a bit to the Fry family, and the Fry family is very important in this story.

“Back in 1920, a white family cared enough for this young man to ensure that his name was included up on the wall at the Memorial.

“They filled out the paperwork for their own son, and they filled out the paperwork for Alexander Bidice, the boy they'd only known for six months.

“They did that for him, and then John Fry wrote a letter and attached it, and that's the only thing that tells us that he is of Aboriginal descent.

“Those pieces of paper are incredibly important; they’re the crux of us knowing as much as we can about him, and to think that the Fry family did this for a young man they’d only known for a short while. It’s pretty special …

“But I’m not finished; there's more to him, and we will keep trying.

“To have a really good future, we need to recognise what happened in the past.

“We just didn't send a bunch of white boys, we sent Aboriginal boys as well, and they need to be acknowledged and remembered.

“To me, if the next generation doesn't know, no one's going to know, and it’s going to be gone.

“I want them to know that here in this town we have our own heroes …

“Whenever I visit the Memorial, I always make sure that I put a poppy on Alex's name.

“No one else knows him. No one else knows he existed. No one else knows anything about him. But geez, I’m pushing for everyone to know.

“I want everyone to know about Alexander Bidice.”

Michael Bell is the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Memorial. He is working to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, who are currently serving, or who have any military experience and/or have contributed to the war effort. He is interested in further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted at Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au