'You’d go a long way to find someone who was more courageous'

Allan Russell was just 21 when he took part in Z Special's Operation Agas 1: "[Kulang's] loyalty was a great comfort...”

Allan Russell doesn’t like to talk about his role as a Z Special operative during the Second World War. He’d much prefer to talk about the courage and bravery of the indigenous Dayak people who risked everything to help him gather intelligence as he trekked for four months through the jungles of Japanese-occupied British North Borneo, home to the appalling prisoner of war camps at Sandakan and Ranau.

It was there that the 21-year-old Russell formed an extraordinary alliance with a local Dusun chief named Kulang while surveying and documenting Japanese movements as part of Z Special Unit’s Operation Agas 1.

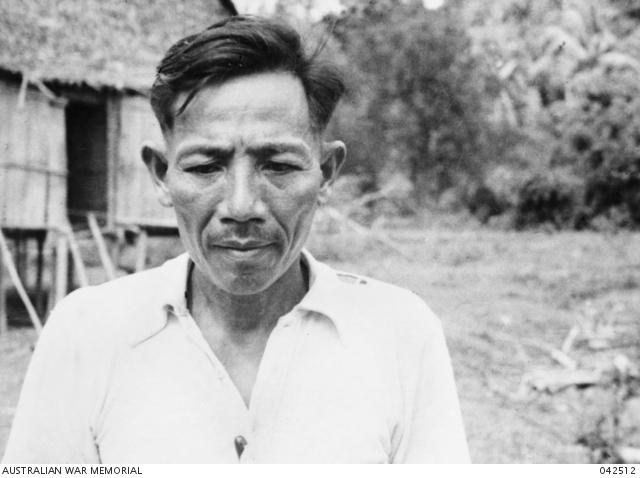

Orang Tua Kulang was the chief of Muanad village. He was trusted by the Japanese, but worked as a double agent, passing crucial information about Japanese movements and activities to Russell and other Agas operatives.

“They talk about courage, but you’d go a long way to find someone who was more courageous than that native, because he worked for the Japanese, and they never woke up to it,” Russell said.

“He used to bring the insignias of the [officers] he’d killed. He had no regards for the other ranks of the Japanese army. He thought they were rubbish, [and that] the only ones you needed to kill were the officers. One day or night, he brought me the insignia which I knew was from a sergeant, and I said to him, ‘You’re lowering your standards a bit aren’t you? This is a sergeant.’ He was so annoyed and upset telling me that he wouldn’t have wasted his time. The ones he wanted were the Kempei Tai. And they employed him. And wondered why their ranks were getting lower and lower.”

Kulang: "They talk about courage, but you’d go a long way to find someone who was more courageous."

Kulang was waging his own secret guerrilla war on Japanese forces, and was instrumental in the rescue and survival of Gunner Owen Campbell, one of only six out of almost 2,500 Australian and British prisoners of war to survive the infamous Sandakan-Ranau Death Marches.

“Owen Campbell got picked up not far from his village, and Kulang took him out by canoe and up further north to the Bongaya River where he was picked up by a patrol boat,” Russell said.

“When they delivered him to the patrol boat – and that was dangerous, more dangerous than the Japanese – they offered food, and the only thing they had left on board [because] they were about to return to their base were … three kilo tins of stewed apple, [so] the canoe was filled up with tins of apple – that’s all there was.”

Russell “had every reason to admire [Kulang's] courage and extraordinary resourcefulness” and they became good friends. The pair “almost shed a tear” at what turned out to be their last meeting, and Kulang presented Russell with an elephant tusk that had hung above his fireplace as a parting gift.

The tusk, which Russell kept for more than 70 years with “suppressed emotion”, is now on display at the Australian War Memorial as part of a temporary exhibition, A matter of trust: Dayaks & Z Special Unit operatives in Borneo 1945. Developed in partnership with the Australian National University and with the support of the Australian Research Council, the exhibition explores the work of Z Special Unit operatives in Borneo and the relationships they developed with the indigenous populations. The exhibition features a photograph of Russell with the elephant tusk in which he is holding a hat and a blow pipe that were also given to him as gifts.

Allan Russell pictured with his hat and elephant tusk: "I wore [the hat] the whole time I was in Borneo."

Russell laughs when he talks about the photo. “It’s most unmilitary,” he said with a smile. “The hat was given to me earlier on in the piece and I wore it the whole time I was in Borneo. It’s like a boater from Eton on somewhere. It’s beautifully woven, but … I had that walking stick and that hat all the time I was there. Very military, I was with that hat and a walking stick.”

More than seven decades later, Russell still has the hat and the walking stick, but he was forced to give up the blow pipe to get the elephant tusk back to Australia.

“You can’t carry much, and eventually I found a Catalina pilot who would take one, but he said he wouldn’t take … my tusk or my blow pipe for nothing. He more or less said to me, ‘You can give me the tusk or the blow pipe, which do you want to give me?’ So I gave him the blow pipe.

“[But] I was very sorry about that … They can really blow those things a long way and they are very accurate … When they hit you, the rest of the arrow dart tends to travel and breaks off in your flesh, and you can’t get it out in the time you need to. You need to be damn quick if you are going to get it out otherwise the [poison] dissolves in your blood and you’re gone …

“The Japanese were terrified of those blow pipes … The people were so good in the jungle. You couldn’t hear them, and … they weren’t afraid of the night … They used to scare the death out of me. They’d come up and put their hands on your shoulder – and it was pitch dark.”

After the war, Russell pushed for various government agencies to send a mission to recognise and reward the locals who had risked not only their own lives, but those of their families, to help prisoners of war and fight against the Japanese forces.

“My only real contribution to the war was when I came back here,” he said quietly. “Being only a sergeant you don’t have any weight … [but] with a lot of effort – and I was energetic in those days – I finally convinced them that they had to do something about rewarding these natives that had taken such terrible risks … I’d always hoped [they would] send me back … to go back and find them, [because] I knew the people… but they sent somebody else.”

Kulang was awarded the King’s Medal, Pacific Star, and the George Medal, but Russell never saw him again. Sixty years after the end of the war, Russell returned to Borneo for his only post-war visit, but Kulang had died many years earlier.

“[He was] a very courageous native chief,” Russell said. “He was a small man – I’m pretty short now that I’ve shrunk, but he was even shorter than I am – and he did one thing that I always thought was amazing. He wore a felt hat – [not one], but two, one on top of the other … Why he wore two, I have no idea, but he did …

“[His] loyalty was a great comfort...”

A Matter of Trust: Dayaks & Z Special Unit Operatives in Borneo 1945 is on display at the Australian War Memorial until 16 September 2018.

Allan Russell with his daughters at the A Matter of Trust: Dayaks & Z Special Unit Operatives in Borneo 1945 exhibition.