Remembering 'Tracker' Murphy

Warning: this article contains images of deceased persons.

Private Archie Murphy, left, with John Morack Smith, seated, taken in the Middle East in early 1918. Photo: Courtesy Marie Smith

Each day, “Tracker” Murphy would sit in the yard outside his corrugated iron hut in Goodooga, NSW, polishing his leather boots, and his bridle and saddle.

When the young girl next door would ask him where his horse was, his eyes would fill with tears.

He had served as a tracker with the NSW Police, and had volunteered for both world wars, serving as a trooper in the 6th Light Horse and as a private in the Volunteer Defence Corp.

How could he tell her he’d had to return his police horse when he left his job as a tracker, or that he’d been ordered to shoot the horse he had ridden into battle in the Middle East? That horse was one of the famous ‘Walers’ of the First World War.

Members of the Bayliss family of Wanganella, NSW, c1900. Pictured, back middle left to right: George Stephens, who worked from Ingrams, and Archie Murphy, who was bought up by the Bayliss family after coming from Queensland at the age of 13 to help drove cattle. He later used his bush skills to become a police tracker. Front: Matilda, Phillip, Matilda, Margaret and Annie. Photo: Courtesy Nicole Jenkins

A tracker from country NSW, Archie “Tracker” Murphy was one of the thousands of Indigenous Australians who served during the First and Second World Wars.

He was born in Wyandra, Queensland, in April 1888, and at the age of 13 was taken in and raised by the Bayliss family of Wanganella after leaving Queensland as part of a team droving cattle into NSW.

Using his traditional skills, Murphy was later employed as a tracker with the NSW Police in Deniliquin and Hay.

When he married Daisy Martha Lewis in Deniliquin in 1917, they already had a young son Percy William Robert Murphy. That same year, Murphy volunteered to serve with the Australian Imperial Force.

He enlisted in Hay at the age of 31 and was allotted to the 34th Reinforcements for the 6th Light Horse.

He embarked from Sydney for overseas service on board RMS Ormonde in March 1918 and was discharged in September 1919.

Sick and wounded soldiers on the hospital steps. Archie Murphy, seated, bottom right.

After the war, Murphy returned to his work as a police tracker in Deniliquin and later in Orange. He helped solve a number of high-profile cases that were reported on in the local newspapers, “was responsible for clever work during the investigations” into the theft of the mailbags from a train travelling between Cowra and Blayney, and “jumped into the river with all his clothes on” to help rescue three girls who had got into difficulties while bathing in the Edward River in Deniliquin in 1925.

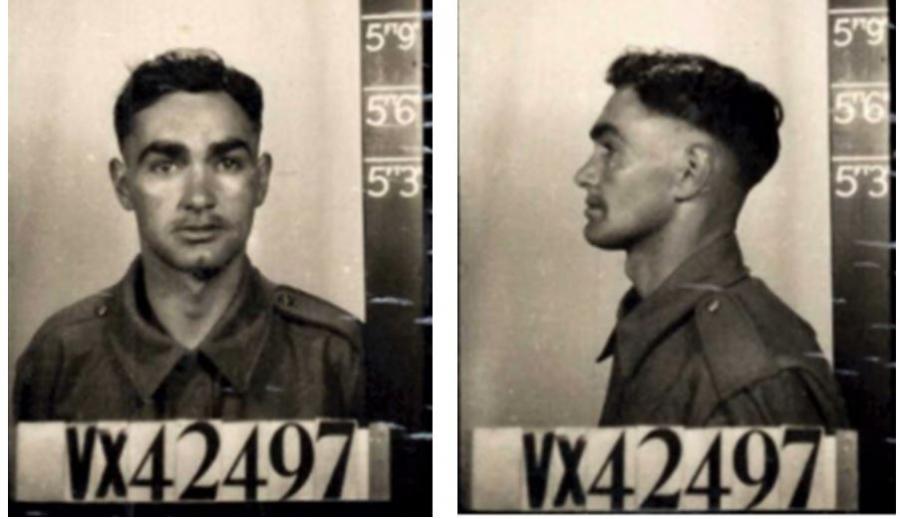

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Murphy volunteered once more, serving as a private in the Volunteer Defence Corp.

His son Percy would also enlist. A labourer from Berrigan, NSW, Percy had been born in Deniliquin in July 1916. He enlisted in Caulfield, Victoria, in July 1940, and served as a private in the 2/29th Infantry Battalion.

His sister, Lena, married another Indigenous soldier, First World War veteran William Edmund Skelly.

Percy died in Deniliquin in October 1971. His father, Archie “Tracker” Murphy died in Walgett Hospital in 1979. He had been granted a soldier settlement block at Goodooga after the war, where he remained until his death at the age of 91. He was buried in an unmarked grave at Goodooga.

Archie Murphy, left, pictured during his days as a tracker with the NSW Police.

Australian War Memorial Indigenous Liaison Officer Michael Bell said Murphy and his son Percy were among the thousands of Indigenous Australians who volunteered for service during the First and Second World Wars despite laws that often prevented them from doing so.

“Despite lack of recognition of rights, denial of citizenship, and concerted efforts at exclusion, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have served in conflicts involving Australian defence contingents since Federation,” Bell said.

“When the First World War broke out in 1914, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had few rights, poor living conditions, and were not allowed to enlist in the war effort.

“Despite this, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people wanted to serve in the defence of Australia, and were willing to change their names, birth locations, heritage and nationality in an effort to do so.

“Many who tried to enlist were rejected on the grounds of race; but many slipped through the net.

Archie's son Percy also enlisted during the Second World War. Photo: National Archives

“They served on equal terms and were paid the same rate as non-Indigenous soldiers, but when they returned home, they often found that discrimination had worsened.

“When the Second World War broke out 20 years later, Indigenous Australians were still not legally allowed to enlist, but many did so, and in 1940 the Defence Committee decided the enlistment of Indigenous Australians was 'neither necessary not desirable', partly because they believed white Australians would object to serving with them.

“When Japan entered the war, however, the increased need for manpower forced the loosening of restrictions and thousands of Indigenous Australian enlisted and served.

“Archie Murphy’s long history of service represents one of the first known Aboriginal men serving the community in uniform in opposition to the government policies and restrictions that were in place.

“His service is a clear indication that Aboriginal people were willing to serve, and that they tried various means to retain their identity and culture in a changing world.”

A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, Bell is researching the military service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent and is working to identify Indigenous Australian soldiers who have served or are currently serving.

“We’re trying to encourage people to come forward and tell their stories to help us tell the broader story of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander experience,” he said.

“Because no-one saw them, perception of their military service was skewed, and for a long time it appeared as if they had never existed.

“We are sure there are many more stories like Archie Murphy’s, so if you know something, please let us know.

“It is a little known story that deserves to be widely known.”

Michael Bell is working to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, or are currently serving, or who have any military experience, and/or have contributed to the war effort. He is interested in further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au

Note: Indigenous elder Olga Collis-McAnespie was the little girl who lived next door to Archie “Tracker” Murphy. In her book, Tracking Tracker Murphy, Olga recounts how she would find “Tracker” Murphy in his yard polishing his leather boots, saddle and bridle. Her mother would buy him groceries – a small tin of powdered milk, a tin of Spam and cigarettes – and lend him flour and a bit of salt for Johnny-cakes. Olga was taught to call him Mr Murphy, and to hold him in high regard as a respected Indigenous elder and Returned Aboriginal Serviceman.