The marvellous Maud Butler

Maud couldn't resist having her portrait taken in her new soldiers uniform. Photo Courtesy: Julie Goodall

Maud Butler was 16 years old when she twice disguised herself as a soldier and attempted to stow away on a troopship bound for Egypt during the First World War.

Her first attempt was in December 1915, just a few days before Christmas.

A coalminer’s daughter from Kurri Kurri in country New South Wales, Maud bought a private’s uniform, cut her hair short to look like a young man, and sneaked on board the troopship HMAT Suevic. She hid herself in a lifeboat, before being discovered out at sea two days later.

Her story caused a sensation in the press at the time. She was described by newspaper reporters as “a clear-skinned, rosy-cheeked, bright-eyed type of healthy country girl”, a “Kurri Kurri Amazon” who wanted to get to the front to do her bit for the war effort. But Maud didn’t actually want to go away and fight.

“I had a terrible desire to help in some way, but I was only a girl,” she told reporters on Christmas Day 1915.

“I wanted to join the Red Cross, and I tried very hard to get accepted.

“I knew it would be no use to stay in Kurri Kurri, because I would never learn to be a nurse there.

“I decided to do something for myself… I took a situation in Pyrmont, as a waitress, and while there I put in my time off trying to get in as a nurse.

“I applied both at the Red Cross Depot and at the Victoria Barracks … [but] I was refused on account of my want of experience.

“The only chance left was to buy a suit of khaki.

“I read a lot about it, of course, and I thought that if I got to Egypt, the Red Cross people there would be only too glad to get me, and to let me do my bit. I read how much overworked they all were.

“There was nothing for it but to stow away and try to bluff it through [so] when I failed [to join the Red Cross] I bought a khaki suit and stowed away.

“I watched how they were worn, and especially how the puttees were put on. I could not resist putting them on to have my portrait taken.

“[But] as time went on I got more and more unwilling to wait, so I went down to see a transport that was lying in Woolloomooloo Bay.

“Oh yes, I was in girls’ clothes then. I saw an officer on board and said I had friends who were going away by ship.

“We had a chat, and we then walked from Woolloomooloo to George Street, Sydney, chatting all the way. I made up my mind to see him again, but as a soldier next time.

“The next morning I went to a barber... He asked me what on earth I wanted to get my hair cut for, and I said I had the fever.”

The unexpected answer made them both laugh. The barber, looking at her rosy cheeks, said simply: “You don’t look it,” and then cut her hair short.

The next evening, Maud put on her uniform and made her way to the docks, looking every bit the smart young soldier. When she saw a sentry at the gangway, her heart reportedly failed her, but the ship was close into the wharf, and she saw a rope hanging from the bow.

“Well, I said to myself, 'Here goes for up the line',” she told reporters. “It was a hand-over-hand job, and I didn't think the boats were so tall. I got up after a struggle and crawled to a lifeboat.”

When the ship left Sydney the following day, Maud crept out of her hiding place, and mingled with the soldiers, joining in their conversations and watching them as they played cards and other games on the deck. All went well, and no one suspected anything was amiss.

There was just one problem: there was no place for her at the mess. With nothing to eat except for a few chocolates that she had brought with her, Maud decided she would raid the kitchen the next night. She never got the chance. She was discovered the following morning when a suspicious officer asked to see her identification disc.

“It was these wretched black boots,” Maud said. “That was the trouble all through. I bought the tunic and breeches from a soldier, and the putties in George Street, and the cap in Bathurst Street. But I could get no regulation tan boots that I could wear. I tried everywhere, but it was of no use. So I had to chance it. I could kick these boots round the room for vexation.”

When she was discovered, the officer and the crew still didn’t realise she was a girl though. She told reporters later that the captain was prepared to let her continue on to the front with them, but when he told her she would have to see the ship’s doctor and pass a medical examination, she confessed. The captain was left with little choice; he told her he would have to put her on a passing ship to take her back home as soon as he could.

Maud Butler being fitted with a life belt before being transferred at sea from HMAT Suevic to the Blue Funnel liner, Achilles. 24 December 1915.

“Then I cried for the first time; it was hard luck, wasn’t it, now?” she said.

“The captain was a jolly fellow. He asked me why I didn’t get tan boots, and that made me cry more…

“He was very nice and kind. They all were. He pretended to scold, but said he would have taken me on if the secret could have been kept. But it was all over the ship in a minute, and there must have been 500 snapshots taken of me.

“They were all very fatherly and kind, but when the captain sighted a ship and told me I was to be transhipped to Melbourne, I broke down and cried. I could not help it. Six months’ struggle all brought to nothing. I was bitterly disappointed that I was not going to lend a hand.

“It was too much for me … They put out a little boat and I went down the side after the sailors. Just as I stepped off I said to an officer at the side of the ladder, ‘Don’t you remember the girl you walked down George Street with?’ He nearly fell off the step to think he had not recognised me.”

Maud was transferred at sea to the Blue Funnel liner Achilles, and arrived in Melbourne on Christmas Day 1915, where she was cared for by the Matron of the Young Women’s Christian Association in Melbourne until she could be travel home to Sydney.

The troops on board Suevic had passed around a hat for her, raising about 30 pounds so that she wouldn’t arrive in Melbourne penniless. The men also wrote about her in their letters and diaries, and on New Year’s Day 1916, three messages in bottles washed ashore near Portland, Victoria. They had been thrown overboard by Australian soldiers on their way to Egypt and had been written on Christmas Day 1915. Several mentioned the enterprising young girl who had disguised herself as a boy and stowed away.

Maud Butler married George Redby Hulme in February 1918 and had three children. Photo Courtesy: Julie Goodall

Maud’s granddaughter, Julie Goodall, only learnt of her grandmother’s exploits after she had died.

“I admonished my mother at Maud’s funeral in 1987, and I said, ‘Why didn’t you tell me?’ I could have asked her about it, but my mother said that my grandmother was embarrassed about it, and that she didn’t want to talk about it any more.

“My mother and her brothers knew all about it of course, but she said my grandmother just wanted to forget about it.

“A few of the newspapers at the time said she was a ‘Kurri Kurri Amazon’, but she didn’t want to go and fight; she just wanted to get over there to help.

“Her idea was that if she snuck onto a ship, and got over to Egypt … they would put her to work in the hospitals as a nurse or a nurses’ aid.

“But she had very small feet; she couldn’t get tan boots in a size to fit her, and that was what alerted the attention of the officer on the ship.

“He initially thought, ‘This soldier’s out of uniform.’ But when he challenged her, everything started to unravel.

“She always said to my mother that if it wasn’t for those bloody black shoes she would have got away with it.”

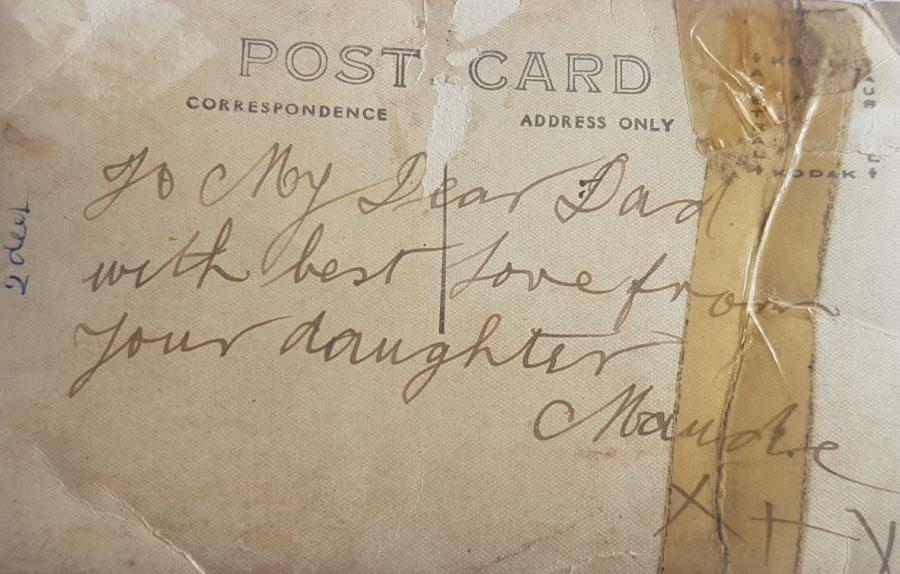

Postcard written by Maud to her father. Photo Courtesy: Julie Goodall

Maud had told authorities on board Suevic that she was trying to get to Egypt to be with her brother Maitland, in the 19th Battalion. But there was one problem with her story. Maud’s brother, Maitland, did not enlist until two years later. His mother Rose complained to authorities that he was under age and that he had enlisted without her permission, so he was discharged soon after. He successfully enlisted later under the alias Frank Emerson, reverting to his real name not long afterwards, and serving with the 2nd Battalion on the Western Front.

“My grandmother was a very smart woman, and she always thought on her feet,” Goodall said. “I think she realised she could get into a bit of trouble for stowing away so she started trying to cover her back a little bit. She told them she wanted to get to her brother in Egypt, but he didn’t actually enlist until March 1917, so think she fudged that one and the chances of her being found out at the time were pretty remote.”

Not to be deterred from her mission, Maud told the reporters at the time that she intended to go to Sydney that night, and “find some way of learning the work and joining the Red Cross service”.

“I have not given up my intention,” she told reporters in Melbourne on Christmas Day. “I am going to Sydney tonight and I will find some way of learning the Red Cross service.

“It is a pity if they cannot find a way for me to be of some service to the poor wounded men. I learned first aid, and was reckoned very good at it. I shall be at the front yet, you’ll see.”

Within months of returning to Sydney, Maud made her second stow-away attempt.

On 7 March 1916, she bluffed her way on board HMAT Star of England, pretending to be a drunken soldier returning from leave.

“She learnt from her mistakes, and she made sure that she had the correct shoes the second time,” Goodall said.

“She watched the ship, and she noticed that some of the soldiers were drunk, so she attached herself to a group walking up the pier and pretended to be drunk as well.

“She’d even created her own identity disc and stamped a false name on it – ‘No. 4850. Private Harry Denton, 15th Battalion, 3rd Infantry Brigade, Australia’ – but for some reason she had acquired a pistol, and I think she overdid it.”

She was discovered the following morning when an officer asked to see her identity disc, and found the name on it didn’t match any of the ship’s records. The ship left Sydney without her and she was charged and found guilty of having wrongfully worn a military uniform.

Maud then abandoned the idea of stowing away, and tried to help the war effort by collecting money for charity instead, but it wasn’t long before she was in trouble with the authorities again.

On 25 April 1916, Maud was arrested by Military Police in Sydney for collecting money while wearing an AIF uniform. At first they did not realise she was a girl. They thought she was a soldier contravening a recent military order that men in uniform could not collect money for the war effort.

During her trial, the assistant secretary of the Returned Soldiers’ Association, Lieutenant Thomas Bathurst, spoke on her behalf. Maud had been asked to collect funds for the association and had already collected £200 in Sydney and Newcastle while wearing the AIF uniform. He advised the court that the association knew of her attempts to go overseas, but were satisfied about her good character. She had worn the uniform in Newcastle with no complaints, and there were thought to be around 200 women and girls collecting money for the war effort in uniform as a novelty. In an age of long skirts, the magistrate was shocked to hear about women and girls going about in trousers. He made her promise never to appear in uniform again.

Maud Butler, in a 1930 issue of Truth magazine.

It was not until after the war that Maud finally fulfilled her dream of becoming a nurse.

She had married George Hulme in February 1918, and had three children, but her husband left when the youngest – Goodall’s mother, Paula – was three months old.

“What a lot of people don’t know about my grandmother is that she went on to be a very well respected nurse and midwife in the Campsie and Canterbury area of Sydney,” Goodall said.

“There was always the danger she would lose the children to the state authorities, so she decided she had to go back to work and find employment. She’d left school when she was 14, so she went back to study at night school so that she could matriculate and enrol in nursing or midwifery.

“My uncle Cliff used to talk about growing up in the late 1920s and how he and his brother Tommy would be sitting there at night, outside the classroom while she studied, and had to be quiet.”

Maud went on to become a registered nurse and midwife and ran a home birthing facility for mothers and babies in Campsie in the 1940s.

Her two sons, Tommy and Clifton, went on to serve in New Guinea during the Second World War.

Maud's passport photo from the 1960s. Maud went on to become a respected nurse and midwife in Sydney. Photo Courtesy: Julie Goodall

Today, Goodall wishes she’d had the chance to talk to her grandmother about her adventures during the First World War. Goodall still has a conch shell that her grandmother gave her after travelling around the world in the 1960s, as well as the medical dictionary that she used when she qualified as a nurse.

“She was incredibly independent, and she was quite determined,” Goodall said.

“She knew her own mind, and she didn’t hold back.

“We would visit her every Sunday, and she was always beautifully presented.

“She was really proud when she ended up qualifying as a nurse, and she always wrote her registered nurse number whenever she signed anything.

“There was no household that wasn’t affected in some way by the First World War, and she took control of her life.

“It really is an amazing story.”