Painting among the ruins

Warning: the following article mentions suicide. If you or someone you know needs help, support is available at Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636. If you are an Australian veteran or family of a veteran, you can also call Open Arms, Veterans & Veterans Families Counselling Service, on 1800 011 046.

Artist Evelyn Chapman at work amongst the ruins of Villers-Bretonneux in July 1919. This photograph shows all that is left of the church of Villers-Bretonneux.

Australian artist Evelyn Chapman sits with her easel in the devastated ruins of Villers-Brettoneaux.

She had visited the battlefields of France just weeks after the end of the First World War with her father, who was attached to the New Zealand War Graves Commission.

In doing so, she became the only known Australian female artist to depict the blasted battlefields and the ruined churches and towns of the Western Front in the immediate aftermath of the war, creating a powerful series of works that bear witness to the human tragedy of war.

More than 100 years later, Chapman’s works are an important part of the art collection at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

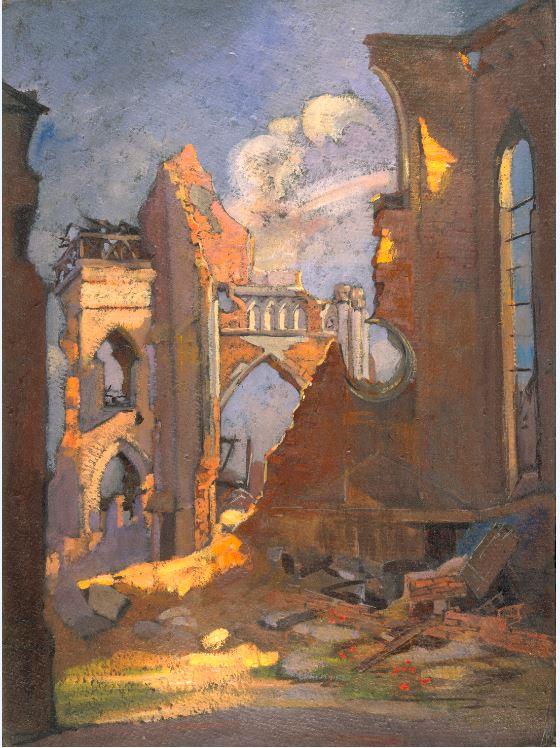

Evelyn Chapman, Ruins of the church of Villers-Bretonneux, 1919, tempera and oil on felt paper.

For Dr Anthea Gunn, a senior art curator at the Memorial, Chapman’s works are a poignant reminder of the devastation and loss suffered by so many during the war.

“Evelyn Chapman is someone we don’t hear very much about,” Gunn said.

“She grew up in Sydney and started training as an artist in the early part of the 20th century.

“She was seen as someone who had great potential, and was something of an up-and-comer of that generation.

“She ends up on the Western Front in the immediate aftermath of the war and creates a really beautiful series of paintings in response.

“They’re rare because there weren’t many people, and certainly not many women at that point, who had the opportunity to do that. But they are also extraordinary because they are just beautiful paintings that really capture the poignancy of the destruction of war.

Evelyn Chapman, Portal of a ruined church at Villers-Bretonneux, 1919, tempera and oil on felt paper.

“She wasn’t just visiting the battlefields and then going back to the studio … She was very much in there, at work in the field amongst the ruins…

“It takes hours to create works like that so it’s really quite extraordinary what she did.

“It would have been incredibly confronting. Her father was literally there to organise the cemeteries, so they would have been seeing the very worst of the battle zones.

“I don’t think you can look at her work without thinking about the loss of life that that destruction means.

“They seem simple, but they really beautifully convey what war means in a way that’s not gruesome; they’re very reflective, and commemorative, so they’re perfect for our collection.”

Evelyn Chapman, Graves in a battlefield, 1919, tempera and oil on felt paper.

Grace Evelyn Chapman was born on 25 October 1888 in Cary Steet, Marrickville, the only child of organist Thomas Francis Chapman and his wife Grace.

She began studying in Sydney in 1906 under the Italian-born artist Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo, with fellow students Grace Cossington Smith and Norah Simpson.

Three years later, she won first prize in the Royal Art Society’s student drawing competition, and in 1911 she painted a portrait of Rubbo, which was bought by the Art Gallery of NSW.

Later that year, Chapman travelled to Europe with her parents, attending the famed Académie Julian in Paris. She gained classical training in life drawing, and was praised by her contemporaries for her “harmonious colour sense”.

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Chapman moved to London with her parents, and spent time in St Ives, Cornwall, a thriving cosmopolitan colony for artists, including some who had fled the war in Europe, where she created vivid works in tempera and oil.

There, she painted a full-length portrait of her cousin, Captain Edmund Warhurst Cornish, who served as an officer in the Australian Imperial Force before joining the Australian Flying Corps. Their personal histories are interwoven against the backdrop of the First World War.

Evelyn Chapman, Ruined church at Villers-Bretonneux, 1919, tempera and oil on felt paper.

Edmund Cornish had enlisted in May 1915, aged 18, serving as a Private in the 13th Infantry Battalion. He served on Gallipoli, and by August 1916 had been transferred to the 45th Battalion, was promoted to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant, and had fought and been wounded in France.

He was awarded the Military Cross for his “conspicuous gallantry” at Gueudecourt in February 1917, and was detached for duty to the 12th Australian infantry Brigade as an intelligence officer. He received a bar to the Military Cross for his actions near Zonnebeke in October 1917.

Cornish was later transferred to the Flying Corps, taking part in one of the last great air battles of the war. He was taken prisoner by the Germans in October 1918, but survived the war, and returned to Australia in May 1919. He was killed in a flying accident near Goulburn, NSW, on 11 February 1929.

Chapman’s portrait, painted when Cornish was only 20, captures his youth and vulnerability. It is quite different from the works she created after the war, when she accompanied her father to the area around Villers-Bretonneux.

Australian and New Zealand forces had suffered heavy casualties as part of the Allies' attempts to defend Villers-Bretonneux in April 1918, creating a powerful and lasting bond between the people and Australia that continues more than a century later.

The scenes of devastation were shocking. Her record of the ruins of the church at Villers-Bretonneaux provide a lasting account of the horrific cost of war.

But Chapman also managed to imbue her work with a sense of optimism and colour, her scenes of devastation and loss featuring plants and flowers growing amongst the ruins. The delicate red poppies – already a symbol of remembrance – offering a powerful message of resilience and hope to a generation devastated by war.

Evelyn Chapman, Interior of a ruined church at Villers-Bretonneux, 1919, tempera and oil on felt paper.

Chapman went on to exhibit at the Salon des Beaux Arts in Paris in 1920 and 1921, but the tragedy of war was never far away.

In 1923, she met Flight Lieutenant Claude Vernon Aristides Bucknall, a pilot who had served with the British during the war.

He was said to be suffering from neurasthenia when he borrowed a friend’s pistol and shot himself in her father’s flat in Kensington.

He had proposed to her just days after they met on the Isle of Wight, and again in London. She had declined both times, saying they had only just met and that she was devoted to her art.

Bucknall visited to say goodbye in September 1923, saying he had been ordered to Mesopotamia. He declined tea, but smoked a cigarette, and talked for some time about Mesopotamia and his prospects there. When he accepted an invitation to stay for dinner, Chapman’s father went to dress for dinner, leaving Bucknall behind with his daughter to say his goodbyes.

While they were alone, Bucknall told her he was not going to Mesopotamia, but that he was going away and that he wished to say goodbye. She had turned away to light the fire, when she heard the shot.

A letter found on his body, and addressed to his mother, was written the day he died.

“I have decided that I can bear this world no longer, so I am going to the next, whatever that may be. The war killed me really. I have never been happy since. I feel happy at the prospect of relief from the hellish torture I am suffering. I cannot sleep and my nights are one long agony. It is no one’s fault but mine.”

Two years later, Chapman married the brilliant but domineering Australian organist and composer George Thalben-Ball.

She never painted again, but she encouraged her daughter, Pamela Thalben-Ball, to become a painter and study art.

She lived out the rest of her life as a wife and mother in Britain, only returning to Australia for a visit in 1960. Chapman died after returning to the UK in 1961, and is buried in Highgate Cemetery, London, alongside her parents.

“It’s very sad,” Gunn said.

“She had the potential of being a really extraordinary painter of that era, and then her career just ended.

“There are so many questions in my mind about what really stopped her from continuing with her art, but there is a strong indication that it was her husband who stopped her from painting,

“She makes this really powerful statement about the scale of destruction and what war actually does, but you also see resilience in woman drawing water amid rubble, or poppies growing in the shattered ruins.

“We have seven of the works she completed in France in our collection, and there are more in the Art Gallery of NSW collection.

“For a woman who is quite removed from the war in one way – although, of course, no one of that generation is really removed from it – it keeps coming up. The threads of her life keep circling around the war, and then this horrible thing happened to her…

“Women at the time were permitted to pursue art, but only to a point. It was all well and good to be a wonderful amateur artist, but if you actually wanted to make your living out of it, then that was seen as crossing some of society’s barriers.

“There’s suggestions that when she did exhibit her work, her father bought them because he didn’t want her to be disappointed. But that actually stymied her work, and then her husband for whatever reason doesn’t make it possible for her to pursue her career.

“She gives up painting, but from what I understand, she writes letters to her daughter about how to handle money and how to make sure that no man is going to stop her from investing in the way that she wants to invest.

“Her daughter moves to Australia and establishes herself as an artist, but she herself says that she wasn’t nearly as good a painter as her mother.

“Her daughter was incredibly faithful to her, and it’s only because of her daughter that we have the collection that we do.

“The flipside of the fact that her father bought all these works, is that they actually remained in the family. In the 1970s, her daughter began placing her mother’s works in collections, and that’s when the Memorial acquired our body of work from her.

“If she hadn’t done that, Evelyn Chapman may well have been lost to history.”

If you, or someone you know requires support, please contact:

Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636.

Defence All-hours support line – The All-hours Support Line (ASL) is a confidential telephone service for ADF members and their families that is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week by calling 1800 628 036.

Open Arms – Veterans & Families Counselling Service provides free and confidential counselling and support for current and former ADF members and their families. They can be reached 24/7 on 1800 011 046 or visit the Open Arms website for more information.

DVA provides immediate help and treatment for any mental health condition, whether it relates to service or not. If you or someone you know is finding it hard to cope with life, call Open Arms on 1800 011 046 or DVA on 1800 555 254. Further information can be accessed on the DVA website.