'There are many, many, stories like mine'

For artist Lee Grant, the Korean War is anything but forgotten. “I wouldn’t exist without that war, and that’s just the reality of it,” she said.

“My mother is Korean and my father was in the RAAF.

“He served in Vietnam, but one of his postings after that was to Korea and during his posting there, from 1970 to 1971, he met my mother.

“If it had not been for the war, there might not have been that relationship with Australia, and my father would not have been posted to Korea, and my sisters and I might not have been born.

“There are many, many, stories like mine, but I imagine my mum being swept off her feet by this western man in uniform.”

Lee's father pictured with her grandparents at the Kyung-Ju temple in Korea. Photo: Courtesy Lee Grant

Decades later, Grant was selected by the Australian War Memorial as the Australian artist for the inaugural artist residency exchange project with the Republic of Korea.

“When the Memorial contacted me, my ears pricked up straight away,” Grant said.

“I’ve been working on a long-form photographic project for almost ten years now about my relationship to that country, and what the Memorial was offering me was the opportunity to add a missing chapter to that broader project, one that I was a bit nervous about ever touching because it’s just so massive and so complicated, but one that was really meaningful to me as well because there’s a such strong connection to the war in terms of my own family history.

Lee's mother and father in Korea with her great-grandmother. Photo: Courtesy Lee Grant

“My mother’s paternal family was quite well off, and very much Yangban1 society … They were wealthy landowners, and as a part of that class, my great-grandfather was an early adopter of western culture.

“Even during Japanese occupation, he really enjoyed jazz music and would parade around in western clothes, but between the end of the Second World War and the start of the Korean War, his enthusiasm for all things Western and his status came back to haunt him … According to family lore he was reported by jealous neighbours to the communists.

“They took him out of his home in the middle of the night and killed him, dumping his body in a mass grave.

“It wasn’t uncommon, and that was the beginning of the end of a privileged lifestyle for his family.

.“My grandparents were only young when they had my mother, and they endured the trauma of that war and also the vestiges of Japanese occupation …

“They literally had to start again. And my mother was actually born one week after the start of the war.”

Towards a field of sleep: Shaman/Shindo ribbons ribbons on Daegwallyeong Mountain

Towards a field of sleep: Anotogaster sieboldii aka General Dragonfly

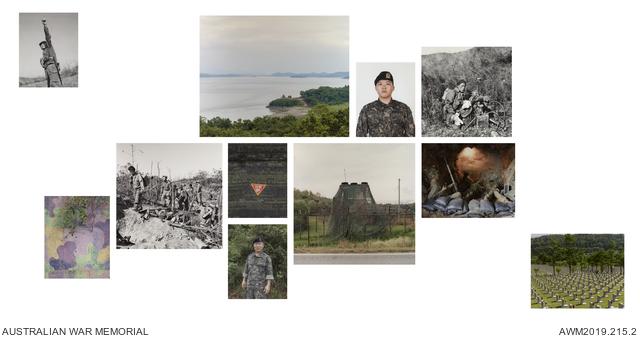

Grant travelled to Korea in 2018 to research the history and legacy of the war and then created Mnemosyne, a series of artworks in response to the shared history of conflict between Australia and Korea.

Named after the ancient Greek goddess of memory and remembrance, Mnemosyne features Grant’s photographs, complemented with archival photographs from the Memorial collection.

The first series of photographs, Towards a field of sleep, presents the Australian experience of the Korean War, while the second, And the rivers still flow towards an open sea, presents the Korean experience.

“In piecing each work together, I wanted people to reflect on the long-term unintended consequences of the Korean War, and war in general,” Grant said.

“My intentions were to have a conversation with the collection and to consider my own work alongside that of other photographers who trod in the same places before me.”

Mnemosyne: Towards a field of sleep.

Mnemosyne: And the rivers still flow towards an open sea

To complete the work, Grant visited historic sites and met with current and former service personnel and civilians who lived through the war. She then met with Australian veterans and undertook research at the Memorial.

“I’ve been going back and forth to Korea for almost ten years now, but this time I had a responsibility and a very particular focus,” she said.

“I was trying to imagine what it might have been like 70 years ago during the war and was looking at the history of that area and exploring the idea of trauma in landscape and what that might look like.

“Korea is quite mountainous, so the landscapes are very beautiful, but they’re also quite harsh; the summers are very hot, and the winters are very cold, but I was there in late summer, so it was almost idyllic.

“It was almost like I was transported back to my own childhood, where I’d spent a lot of time on my grandmother’s farmlet in north-west New South Wales, and those moments of deep silence, punctuated by, in this instance, the sound of dragonflies humming, or the sound of the wind rustling through the corn stalks or the rice paddies.

“There was something quite beautiful that transported me back to what life might have been like until the war hit, and then living and sleeping through this barrage of military exercises also evoked that sense of terror that you might have experienced back then as a civilian.”

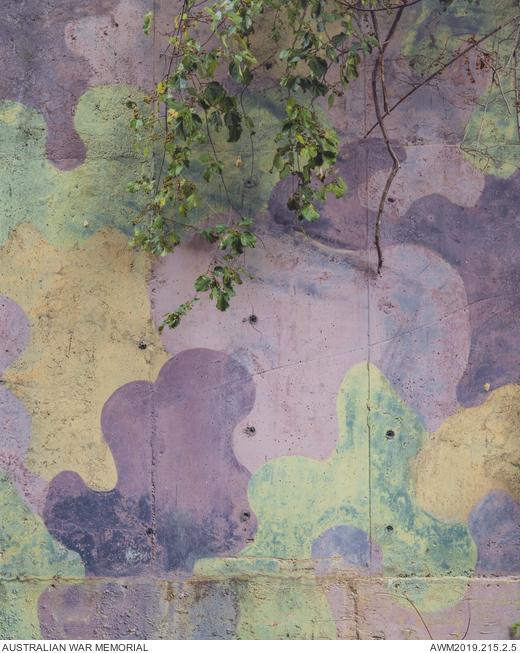

And the rivers still flow towards an open sea: Korean Camo.

And the rivers still flow towards an open sea: Mine warning sign in the DMZ

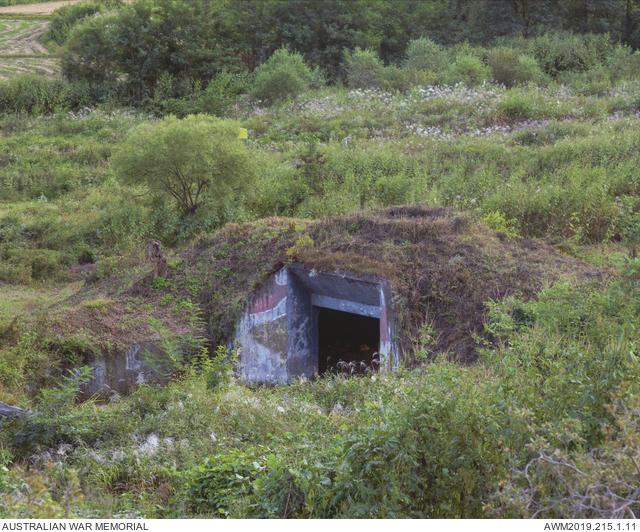

Grant spent almost two weeks living in a village in the demilitarized zone, the four-kilometre wide, 250-kilometre long stretch of no man’s land that has divided North and South Korea since 1953.

“I had an incredible amount of freedom, but my presence was also rather confusing to the military; they were a bit like, ‘What the hell are you doing here?

“The first day I was driving around with my translator and fixer, and we were quite independent, but of course I’m photographing, and somebody sees me from a military outpost, and suddenly there are a bunch of military jeeps zooming in and people saying, ‘What are you doing?’

“There were also a lot of live fire exercises, which is apparently very normal, but as an Australian, I’m not used to that. There were explosions going off, all day and all night, and to be honest, it was quite disconcerting.

“I spoke about it the next day with my translator and she just laughed. She said, ‘It’s actually very quiet at the moment because relations are so good; you should be here when it’s not so good.’

“The vestiges of the war are really apparent there. You don’t notice it in Seoul or other parts of Korea, but you certainly do along the border.

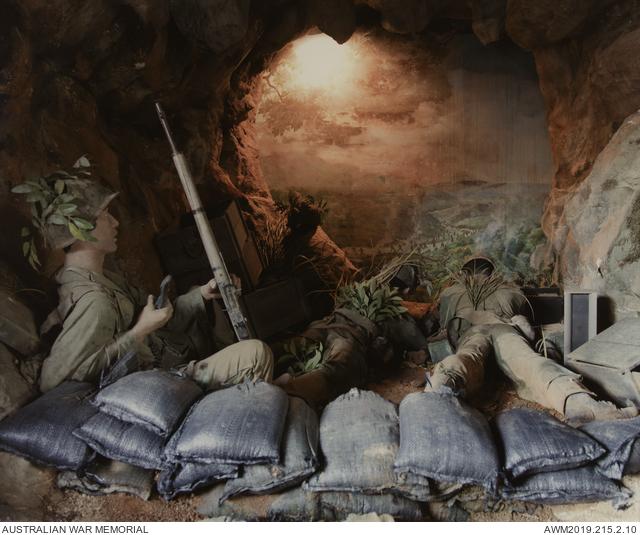

And the rivers still flow towards an open sea: A diorama of war at the Historic Park of Geoje POW Camp

Towards a field of sleep: Hantan-gang.

Towards a field of sleep: An abandoned military bunker in the DMZ, now used for training purposes

Towards a field of sleep: Summer Chrysanthemums

“It’s alive and well, and that history is still speaking, so I guess I wanted to use a kind of visual poetry to evoke a sense of time and space, but also a sense of trauma and the legacy of that trauma too.

“I don’t know if I’ve succeeded, but I like to think I’ve tried.

“[Mnemosyne] was my emotional reaction to some of the spaces I was photographing, and how I imagined history unfolding in some of those spaces.

“It was also, I guess, inspired in part by my own family history and the way in which my great-grandfather was killed.

“In some ways, it’s a way of me trying to understand my own history and where I fit into that, but it’s also a way of exploring themes that are really important to me, themes like trauma, belonging, identity, connection, landscape, and a sense of culture: how we identify and belong to one culture, or another – or how we might not.

“I’m super grateful to the Memorial, but also to the curators … who let me loose amongst the collection and trusted me to create something that I’m actually very proud of as an artist.

“It really has meant a lot to me, both professionally and personally.”

Towards a field of sleep: October skies over the Korean War Memorial

1 The Yangban were part of the traditional ruling class or gentry of dynastic Korea during the Joseon Dynasty. The yangban were mainly composed of civil servants and military officers —aristocrats who individually exemplified the Korean Confucian idea of a “scholarly official”.