'It was a real labour of love'

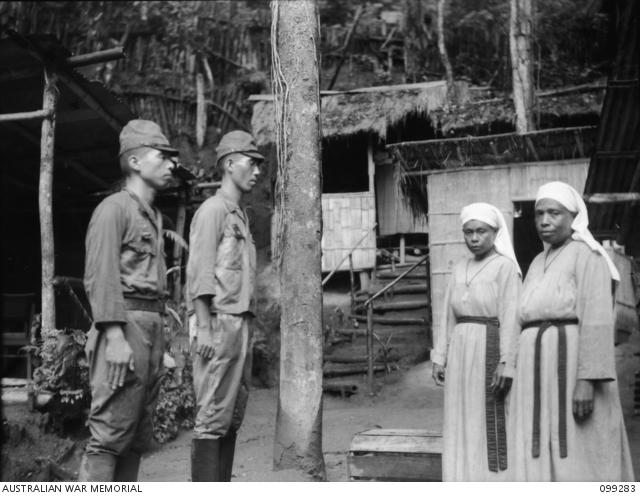

Ramale, New Britain, 14 September 1945. Daughters of Mary Immaculate, or F.M.I. Sisters, who risked their lives to deliver food to missionaries and civilian detainees held captive for three and a half years in New Britain during the Second World War.

When the Japanese invaded Rabaul on New Britain in January 1942, a group of 45 F.M.I. Sisters refused to give up their faith. Instead, they risked their lives to help save hundreds of Australian and European missionaries and civilian detainees who were held captive by the Japanese for three and a half years, first at Vunapope and then in the dense jungle of Ramale.

More than 75 years later, Lisa Hilli, an Australian artist of Gunatuna (Tolai) heritage, discovered their little-known story while researching Australia and Papua New Guinea’s shared war history as part of a creative commission for the Australian War Memorial, supported by the Anzac Centenary Arts and Culture Fund.

It was while she was researching in Rabaul that she first learned of the Daughters of Mary Immaculate, or F.M.I. Sisters, of the Vunapope Catholic Mission. These remarkable Tolai, Bainings and New Guinea Islands women had helped to save the lives of hundreds of men, women and children in New Britain during the Second World War.

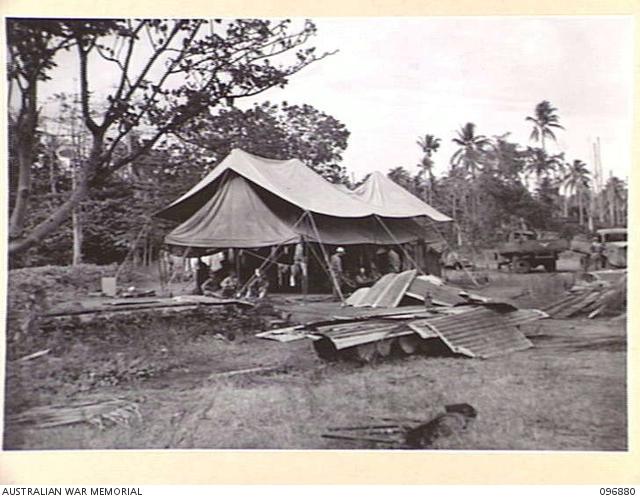

Ramale, New Britain, 16 September 1945. View looking down on the mission, the home of 300 internees, mostly Catholic Missionaries.

“Vunapope in my language of Kuanua means place of the Pope,” she said. “It was a Catholic mission, which was established by European missionaries, so a lot of European and Australian missionaries were based there from the late 1800s. When Japan invaded Rabaul in 1942, a lot of the Australians were evacuated, but the ones who stayed behind evacuated to Vunapope, and so Vunapope became this refuge, or safe haven, for a few months.”

Vunapope was eventually taken by force by the Japanese, and in October 1942, the Japanese set up an internment camp to hold the Europeans, Australians and mixed-race children.

“It was only due to the courageous acts and efforts of Bishop Leo Scharmach that their lives were spared at all,” Lisa said. “He was Polish, but he managed to convince the Japanese that he was German and they should spare the lives of the missionaries and the mixed-race children who were there at Vunapope.”

Ramale, New Britian, 16 September 1945. Bishop Leo Scharmach, pictured on the left, wearing a white hat and glasses. The Bishop convinced the Japanese he was German and helped save the lives of the men, women, and children who were interned at Vunapope and then Ramale.

The bishop is said to have told the Japanese he was the Adolf Hitler’s representative in New Guinea and that they had to respect his status and those under his care.

At about this time, the Japanese declared that the Indigenous people of New Britain, including the F.M.I. Sisters based at Vunapope, were ‘free’.

“When the Japanese invaded the then Australian territory of Papua and New Guinea, they ‘liberated’ all the Papua New Guineans and held all the Australians and Europeans captive,” Lisa said.

“The Japanese said, ‘You’re free; you don’t have to worship your western masters’ religion anymore’ … but the F.M.I. Sisters were completely loyal to their faith, and to their religion, and to their service to the Catholic missionaries.

“The F.M.I. Sisters basically risked their own lives and provided food for the Catholic missionaries and for the Australians and Europeans whilst they were held at Vunapope. They refused to give up their faith.”

Vunapope, New Britain, 16 September 1945. Japanese naval guards at Vunapope Mission watching the Australian party come in for the evacuation of Catholic Sisters and Priests from the Ramale Valley internment camp.

When Vunapope was destroyed during the Allied counter-offensive in June 1944, the Japanese marched 300 men, women and children six kilometres away into the dense jungle valley of Ramale.

The internees represented 17 different nationalities and came from countries such as Germany, Austria, Belgium, Netherlands, France, Italy, Ireland, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Sweden, America, Canada, Britain and Australia.

Despite Japanese efforts to stop the F.M.I Sisters from engaging and practising Christianity with the Australian and European Sisters, the women continued to devote themselves to God. They were determined to help keep the Australian and European missionaries alive by growing and harvesting fresh produce and delivering heavy baskets of it over gruelling distances, up and down a steep incline.

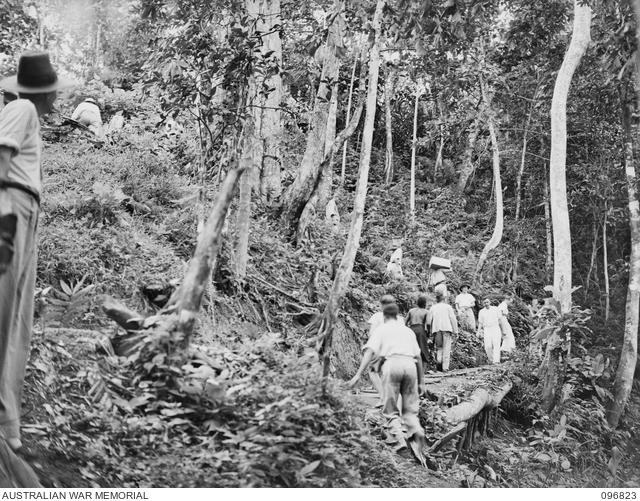

Ramale, New Britain, 16 September 1945. After the internees were liberated, food was brought from Rabaul and carried downhill to the camp. The F.M.I. Sisters had risked their lives carrying baskets of fresh produce through grueling conditions to help keep the 300 Australian and European internees alive during the war .

“They disobeyed the Japanese, and they stayed true to their vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, even in war,” Lisa said.

“They started building gardens and growing food, and every day they would bring heavy bags of fresh produce, carrying them on their heads.

“The Japanese would stand guard at the top of the valley, and inspect the food to make sure they weren’t smuggling anything else in.

“They would then take the best of the food, and the Sisters would walk back down into the valley and give the rest of the food to the prisoners of war. And they did that every day.”

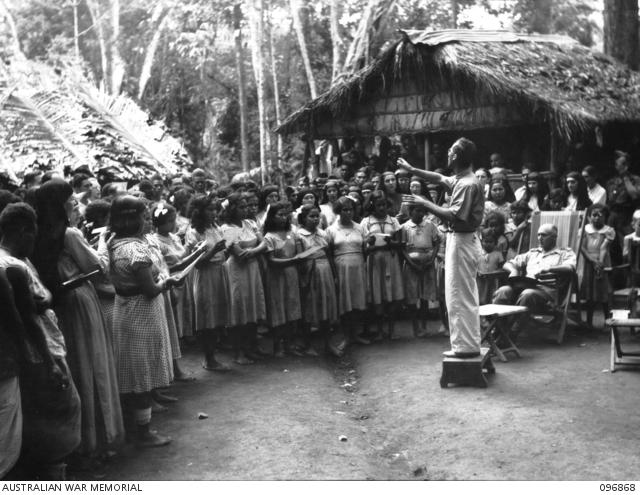

Ramale Valley, New Britain, 14 September 1945. A choir comprised of the internees at Ramale Valley Internment Camp singing for Major General K.W. Eather, General Officer Commanding 11 Division.

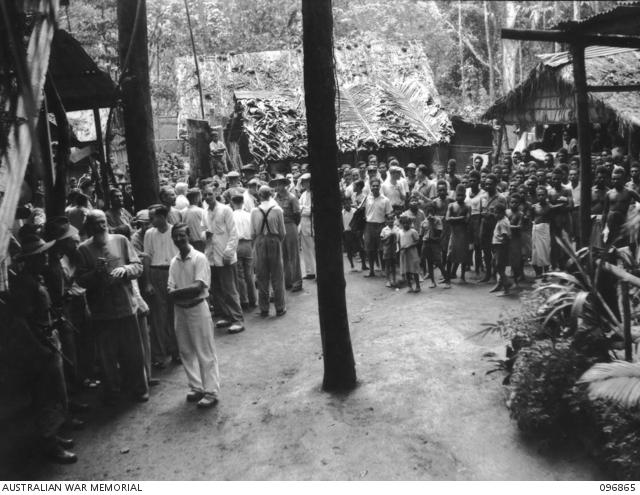

Ramale Valley, New Britain. Some of the inmates at the Ramale Valley Internment Camp. Contact with the camp was made by Allied troops and representatives of the Australian Red Cross following the surrender of the Japanese. The internees had to wait for several months in Ramale Valley until suitable buildings were prepared for them. Vunapope Mission had been razed to the ground.

The Ramale camp was liberated by Australian troops on 14 September 1945 when troops of HQ 11 Division occupied the area following the surrender of the Japanese.

“It’s an amazing story, and it’s been sitting there for 75 years, just waiting to be found,” Lisa said. “The F.M.I. Sisters kept them alive essentially, but no one had really looked at them, and honoured them for it.”

Lisa has since created an artwork in recognition of their strength, labour, and dedication. To complete the work, she relied heavily on a draft 100-year history from Sister Margaret Maladede at Vunapope and research at the National Library of Australia and the Memorial. The resulting artwork features a large digital photographic collage of an image of the Sisters from the Memorial’s collection and a series of 45 hand-embroidered cotton cinctures, or religious belts worn by the nuns.

Ramale, New Britain, 2 October 1945: Former internees singing Ramale Greets You at a concert staged as thanksgiving for the liberation of the camp. Personnel of the 11 Division attended.

Bitagalip, Ramale Mission, New Britain. The Mission Choir practising for Christmas festivities in December 1945.

“For me, it was really significant, and I felt really honoured to be asked [to complete this commission],” Lisa said.

“I was actually born at Vunapope, and the more I researched into the history of these Sisters, the more it revealed to me the significance of that place, and made me feel really connected to it.

“Their convent is in the lands that I’m from, and the year that the F.M.I. Sisters became their own independent Indigenous-led convent was the year of my birth – 1979 – so throughout the commission there were all these beautiful layers of connection for me.

Ramale Valley, New Britain. A group of Sisters waving as they prepare to move out of the Ramale Valley Internment Camp.

Sisters and Priests boarding an Army barge for transfer to the motor launch Gloria. They are being evacuated from Ramale Valley to Rabaul.

“Military history from the Second World War is everywhere in Rabaul; it’s just evident everywhere you go.

“I remember my mother always told me that during the war my grandmother … would lie flat on the ground whenever the planes would fly over and pretend that she was dead. That was my only real understanding of the war in my homelands and how that impacted my family.

“Rabaul was largely a war from the air, and when the Japanese flew in, they dropped bombs everywhere, and I remember thinking about the fear that my grandmother would have felt.

“Then when I found an image of the F.M.I. Sisters in the Memorial archives, taken on the day the Australian troops came in and liberated the camp, I couldn’t believe it.

Artist Lisa Hilli paid tribute to the women through her art, creating a large digital photographic collage of an image of the Sisters from the Memorial's collection and 45 hand-embroidered cinctures.

Ramale Valley, 2018. Artist Lisa Hilli visited the site of the camp as part of her research. Photo: Lisa Hilli

“It was so hard to find any information about them. This is the problem when it comes to archival records about black or Indigenous people; their records aren’t always there, so I had to dig really deep into the archives to find anything about them.

“It’s an incredible story and it’s really important for me to be able to share Papua New Guinean women’s stories, particularly related to war, because women’s stories aren’t always told, particularly in war or the military, and then you add another level of being black or Papua New Guinean, and it’s like, good luck. So to find this, and to be able to highlight it, and reveal it, was just really special.

“It’s a legacy for my own people, so it’s really significant for me to be able to do that.”

The watercolour flowers in the artwork were carefully selected to represent the different nationalities of the men, women and children who were held captive at Ramale. The Sister in the middle is holding a sprig of wattle, a reference to Australia and to the Australian soldiers who liberated the camp.

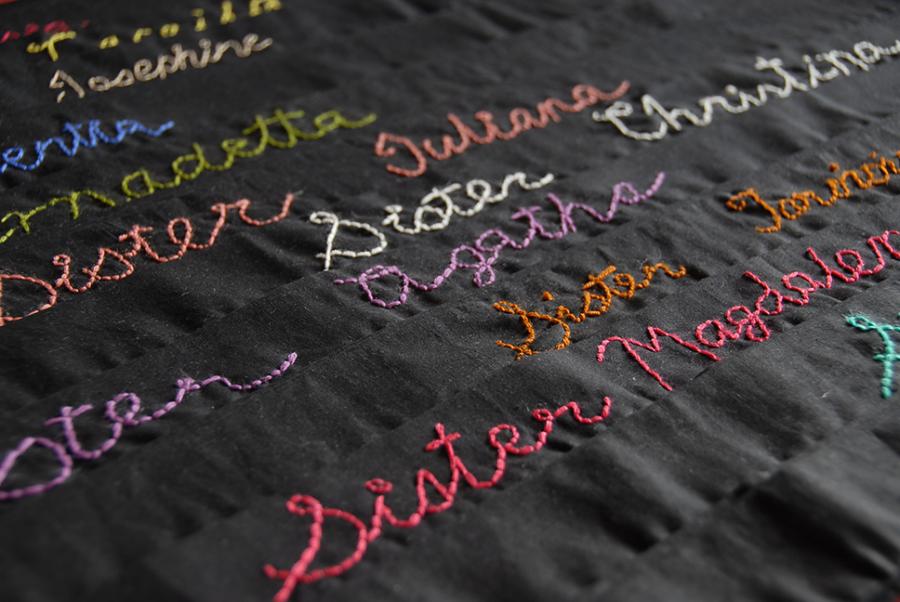

A detail of the stitching on the cinctures. There are 45 cinctures to represent each of the 45 Sisters.Photo: Lisa Hilli

For her artwork, Lisa adorned the Sisters with flowers in reference to the different nationalities of the men, women and children who were held captive at Ramale. There’s the iris to represent the French, the poppy to represent the Belgians, the cornflower to represent the Germans, and a Korean hibiscus to honour the South Korean comfort women that were brought over by the Japanese. The wattle in the middle is a reference to Australia and to the Australian soldiers who liberated the camp at Ramale, while the 45 hand-embroidered cinctures represent each of the individual F.M.I. Sisters.

“Only 12 or 13 of these women were photographed, but there were 45 of them, so I wanted to make sure that they were all recognised and honoured,” she said.

“I was really interested in the Sisters’ habit as an item of clothing that signified the practice of their faith. The black cincture they tied around their waist was a very distinct item of the habit that was worn only at the time. They don’t wear it today, and so I kept coming back to it as a really significant piece of clothing from that war history period.”

The the F.M.I. convent at Vunapope with 100 year memorial. Photo: Lisa Hilli

A memorial Sister Margaret Maladede created for the 100-year anniversary of the F.M.I Congregation, showing the names of the 12 F.M.I. Sisters who died during the Second World War. Photo: Lisa Hilli

The four-metre long cinctures were made using a simple black cotton fabric to reflect the Sisters’ modesty, and each is slightly different. The names of 12 Sisters, found on a Memorial in Papua New Guinea, have been lovingly stitched into them, leaving room for more names as they come to light.

“Every time I sat down to stitch into those cinctures, I had to think about the women, and the work and the labour that they did,” Lisa said. “It wasn’t light work what they did, so there was a real heaviness in honouring their names and ensuring that I put weight into stitching every single stitch.”

New Britain, 5 December 1945. Two F.M.I. Sisters identifying two Japanese soldiers who had tortured them. A small group of the Sisters were tortured by the Japanese and gave evidence during war crimes trials in 1945/6.

She worked with Australian textile artist and friend, Eddy Carroll, to stitch the names into the cinctures, and has since found 30 more names to add to them.

“It was a real labour of love, and it was a really great way to bring back that Australian/Papua New Guinean connection,” she said. “I hope that the artwork is an entry point for people wanting to know and understand more.

“It was a real gift to have to be able to go into such in-depth research and then make something that I was really proud of…

“They really were amazing women.”