'It was an expedition between two worlds'

Official War Artist Susan Norrie filming in Iraq. Photo: AWM2018.1332.642

Susan Norrie has never shied away from difficult subjects.

But when the Sydney-based artist was commissioned by the Australian War Memorial to be an official war artist in Iraq, she had to think twice before accepting the role.

“I had never actually been to the Australian War Memorial,” she said.

“I hadn’t even been on a school trip there, and I did actually demonstrate against the Iraqi War, which so many people did, in Sydney in 2003.

“I was honoured because I could see that it was quite an honour to be given this position, but at the same time, I was conflicted in relation to my issues around war.”

Norrie at work in Iraq. Photo: AWM2018.1332.641

Originally trained as a painter, Norrie explores social, political and environmental issues through video and installation art, as well as in painting, photography and documentary-style film. Today her projects are primarily concerned with the environment, human rights and survival. Through her work Transit, she examined the aftermath of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami that caused widespread flooding and the meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power plant in Japan. She also represented Australia at the 52nd Venice Biennale with her large-scale video installation, HAVOC, based on the Lusi Mud Volcano in East Java, Indonesia.

She travelled to Iraq as an official war artist in November 2016 during a period of heightened conflict in the fight against the terrorist group Daesh (also known as Islamic State, ISIL or ISIS). The Australians were training Iraqi soldiers and assisting in coordinating a strategy for Iraqi troops to retake the city of Mosul.

Norrie travelled to Iraq in November 2016. Photo: AWM2018.1332.643

Norrie spent ten days embedded at Camp Taji, a training compound just north of Baghdad, where Australian, American and other coalition soldiers were stationed. Established by Saddam Hussein as a base for the Iraqi Republican Guard, Camp Taji was the largest and most advanced military base in the country.

“At the time, I wasn’t totally sure of what I was even going to film there,” Norrie said.

“The battle of Mosul had started two weeks before we arrived, and it was a very frustrating time for a lot of the soldiers, because they really wanted to be there up in Mosul.

“They were training the Iraqi soldiers to defend their own country, and they were interested in the historical aspect of the Memorial, but they couldn’t work out what the hell I was doing.

“So I had to find my own voice...”

Norrie at Camp Taji: "I had to find my own voice." Photo: AWM2018.1332.645

Norrie wanted to explore the history of the Middle East and the impact of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, a secret wartime treaty between Britain and France, signed in May 1916. It outlined how most of the Arab lands under the rule of the Ottoman Empire would be divided into British and French spheres of influence at the end of the First World War. The agreement led to the division of Turkish-held Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Palestine into various French- and British-administered areas, causing lasting resentment. Its impact is still being felt today.

“I had done a lot of research about the Middle East in relationship to the historical impact of the Sykes–Picot Agreement between Britain and France, which divvied up Iraq and was then ratified by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919,” Norrie said.

“My project would be a two-fold project looking at Iraq and the day-to-day activities at Camp Taji, juxtaposed with historical reference to the Treaty of Versailles and how that impacted on the Iraqi people.

“I decided to create a visual diary of sorts to capture the everyday circumstances of the Australian, New Zealand and Iraqi soldiers based there ...

Norrie spent 10 days with troops at Camp Taji. Photo: AWM2018.1332.663

“At all times, non-combat personnel like me were accompanied by at least four armed soldiers ... Such was the precarious nature of everyday existence.

“Body armour was compulsory, even within certain predetermined ‘safe’ destinations, despite the ever-present bodyguards.

“There was a gate between the Iraqi camp and the Allied camp and we had to go through that every day.

“Despite the supposed unified military focus against the threat of ISIS, there was great fear still ... always a cloud of suspicion and caution hanging over the camp ... always a sense of pending danger ... the possibility of interlopers and betrayal.”

The 'General's Garden' at Camp Taji. Image: Courtesy Susan Norrie

Norrie visited what she now calls “The General’s Garden” on what was to be her last night in Iraq.

“We went across at twilight and it was pretty amazing,” she said.

“A journalist who was in Taji at the same time had introduced me to the commanders of both the Australian and New Zealand troops. He was also able to get access for me to enter the Amber Zone, where I was permitted to film in the Prayer Room. And amazingly, through his influence, I was able to secure an invitation to visit the Iraqi Commander-in-Chief.

“One of the Australian colonels told me that the general couldn’t imagine surviving such a hostile environment without signs of life around him …

“Perhaps I imagined a place of solace that he had established for himself at his headquarters within the Iraqi camp.

“With hindsight, it was an expedition between two worlds.

“Looking back at the footage, the garden bathed in soft evening light possess the quietude one could easily associate with any backyard in a suburban world … the freshly mown lawn, the chicken coop, the twittering birds and, believe it or not, a swing seat.

“It was as if time had stopped; that this was not in the middle of a war zone, but in the garden of some well-kept home ...

“The general’s quarters, his garden and prayer room, ignited the imaginative potential I was seeking for my project.”

Norrie, left, with Iraqi poet, actor and playwright Salah Al-Hamdani, centre, at the Palace of Versailles. Image: Courtesy Susan Norrie

When Norrie returned from Iraq, a friend in Paris introduced her to the exiled Iraqi poet, actor and playwright, Salah Al-Hamdani. Al-Hamdani had served with the Iraqi Army and was imprisoned as a political dissident in the 1970s. He began writing in prison, and has been living in exile in France for more than 30 years.

“It was such an amazing coincidence,” Norrie said.

“He was actually at Camp Taji himself, which was just incredible.

“A dissident former soldier who escaped the brutal regime of Saddam Hussein, he encapsulates the importance of speaking out ... of voicing resistance.

“His reminiscences and opinions about the current conflict are a powerful counterpoint to the harsh realities of camp life.

“I was incredibly fortunate to have met him.

“He’s an amazing man.”

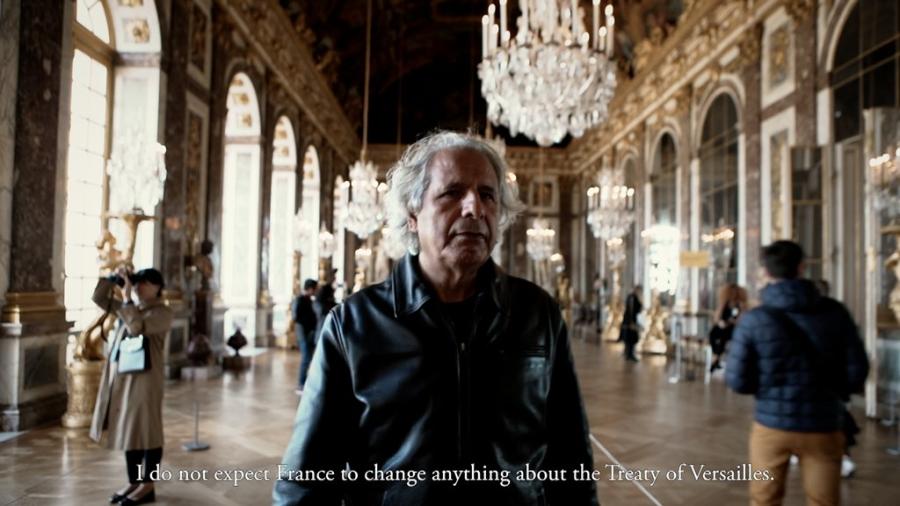

Stills of Al-Hamdani at the Palace of Versailles. Images: Courtesy Susan Norrie

Norrie decided to juxtapose the sequences she filmed at Camp Taji with footage of Al-Hamdani at the Palace of Versailles and excerpts from a series of interviews she did with him.

Al-Hamdani speaks about his history, his years of military service and imprisonment, as well as his thoughts on the conflicts in the Middle East, how they relate back to the agreements made more than 100 years ago, and the current and ongoing struggles of the Iraqi people.

The result is Spheres of Influence, a film-based work now on display as part of Art in Conflict, a touring exhibition of contemporary art from the Memorial’s collection.

A showcase of diverse responses to war, the exhibition features more than 70 paintings, drawings, films, prints, photography and sculptures by Australian artists such as Khadim Ali, Rushdi Anwar, eX de Medici, Denise Green, Richard Lewer, Mike Parr and Ben Quilty.

Stills from Norrie's work Spheres of Influence. Images: Courtesy Susan Norrie

Norrie’s work invites the viewer to contemplate where we have come from, where we are now, and where are we going.

“As an artist, my main interest is in humanity, and so that’s where I’m coming from,” Norrie said.

“I’m interested in life. And I’m interested in what’s happening politically in the world, and I’m responding to that.

“I’ve always been interested in story telling in various forms ... and so I combine art, documentary and film as a way of developing stories.

“It’s a short film, but it’s also a mixture of documentary, film and art...

A still from Norrie's work Spheres of Influence. Image: Courtesy Susan Norrie

“I became more and more focused on the people of Iraq … you just can’t help but feel for the people and think, ‘God, bloody hell, this thing about war, it’s just decimated so much of people’s lives.’

“The Iraqi people are so incredible – the translators I met, the people cutting their hair, and on the boardwalk, and the soldiers: they were really amazing characters, and I felt I just wanted to honour them.

“To a degree, my work deals with the tragedies of the world, but it’s also very much about the mysterious forces of the world.

“We’re living in such complex times ... I just felt that as an artist, it was important to deal with the anomalies of our times...

“I had to follow this story through.”

Art in Conflict is now on display at the Perc Tucker Regional Gallery in Townsville, Queensland. For more details, visit here.

Artists’ talk: Join artists Susan Norrie and Shirley Macnamara on Sunday 12 March at 10.30 am for a free artists' talk. No bookings required.