Australians and New Zealanders who served on the Serbian Front of the First World War

"KANGAROOS ONLY" being painted on a water can by a member of the Scottish Womens Hospital. Serbian front. c. 1914 - 18

More information

On 28 June 1914, young Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. Europe had been in a state of uneasy tension for several years, and this act became the trigger that launched some European nations into action. Exactly one month after the assassination, 28 July 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, effectively beginning the First World War.

For most Australians and New Zealanders, the focal points of the war were Gallipoli, Palestine, and France and Belgium on the Western Front. However, the war was also fought in a number of other theatres, including the Balkans. As a result of the war, and a concurrent typhoid epidemic, Serbia lost 28 per cent of its population, by far the highest casualty rate in proportion to any nation involved in the conflict.

Although the vast majority of Australian and New Zealand involvement in the First World War took place in the theatres listed above, there was a small but significant number of Australians and New Zealanders directly involved in military and medical operations in Serbia. Before the Anzacs landed at Gallipoli in 1915, Australian and New Zealand medical volunteers were already in Serbia, treating wounded soldiers and fighting the typhus epidemic. As many as 1,500 Australian and New Zealand soldiers, airmen, sailors, doctors, nurses and medical staff have been identified to date as serving on the Serbian Front during the First World War.

Although a long way from the Antipodes, Serbia and its desperate plight was widely reported on in the Australian and New Zealand press with great sympathy.

The Australian author, Miles Franklin, with Serbian medical orderlies at a Scottish Women’s Hospital in support of the Serbian Army, 1917 State Library of New South Wales PX*D 250/1 photo 68a

Serbia and the First World War

Europe, August 1914.

Map source: Our Forgotten Volunteers: Australians and New Zealanders with Serbs in World War One, Bojan Pajic

By 1914 the Balkan Peninsula had been the scene of the forced annexation of Bosnia by Austria–Hungary in 1908 and the First Balkan War of 1912–13, during which Serbia and other states liberated territory from Ottoman Turkish rule. In the Second Balkan War of 1913, Bulgaria tried unsuccessfully to seize territory from Serbia in Macedonia. Serbia had gained territory, but its army was seriously depleted.

The declaration of war on Serbia by Austria–Hungary in late July 1914 triggered the mobilisation of the Russian Army in Serbia’s defence. Even as European treaties and agreements saw the seemingly inescapable toppling of more and more nations into war, the exhausted Serbian Army was desperately preparing itself to defend against an invading Austrian-Hungarian Army. The year 1914 saw the Serbian Army successfully resist three Austro–Hungarian offensives, suffering heavy casualties in the process.

In September 1915, Bulgaria, which had been undecided as to which side to join, declared for the Central Powers and moved with Germany and Austria–Hungary to secure an overland supply corridor to Ottoman Turkey through Serbia. On 7 October 1915 the Austro–Hungarians and Germans attacked from the north, and a week later the Bulgarian Army attacked Serbia from the East. The Serbian Army was forced to conduct a fighting withdrawal southwards. At the same time, a joint force of British and French troops, concentrated in the Greek port of Salonika (now Thessaloniki) with the intention of helping Serbia.

This help was too little, and came too late. The Serbian Army, unable to link up with its allies to the south, was forced to conduct a major withdrawal through Montenegro and Albania to the Adriatic Sea coast. Accompanied by tens of thousands of Serbian refugees, the retreating force arrived depleted by hunger, disease and war, with the survivors largely starving, sick and exhausted. Most were evacuated to the island of Corfu to recover, with the evacuation from Albania completed on 10 February 1916. Thousands more would die in the weeks that followed, badly affected by exhaustion and illness from the march.

It took six months for a smaller reconstructed Serbian Army to take up active operations again. The Serbian Army joined with French and British troops along Serbia’s southern border to confront Bulgarian and German armies now occupying Serbia. The Serbian Army led an allied offensive back into Serbia in late 1916 and recaptured the Serbian town of Monastir. A reasonably stable front against the Central Powers was established in southern Serbia throughout 1917 and early 1918. In May 1918, with Greece now having joined the allies, active operations resumed against the Central Powers, and in September 1918 the Serbian Army led a general allied attack that liberated Serbia from the occupying German, Austro–Hungarian, and Bulgarian armies.

The invasion of Serbia and Montenegro in October 1915 by Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria.

Map source: Our Forgotten Volunteers: Australians and New Zealanders with Serbs in World War One, Bojan Pajic

Balkans, Greece. c. 1918. A Serbian Army front line trench in rocky country which made the digging of deep trenches an impossibility. (Donor British Official Photograph SAL760)

More information

The Typhoid Epidemic of 1914–15

In 1914, Serbia was a small, mostly agrarian country with a population of four million. The attacking Austro–Hungarian forces of 1914 brought a strain of typhus into the country that began to have an effect on the local population. In December 1914, a second strain was thought to have been brought by Serbian forces returning from Albania. These combined into a severe epidemic that raged for months, costing tens of thousands of lives in the first half of 1915. Serbian doctors and nurses were among the worst hit, with the country losing over a third of its doctors to the epidemic. With less than 240 doctors remaining to manage the epidemic, foreign medical volunteers and supplies were sought to replace them. Official and volunteer organisations and individuals from France, Britain, Russia, Greece, the United States, Holland, Switzerland, and Denmark responded by sending teams of doctors and nurses, medical supplies, and entire hospitals. Australians and New Zealanders came as part of British missions to Serbia.

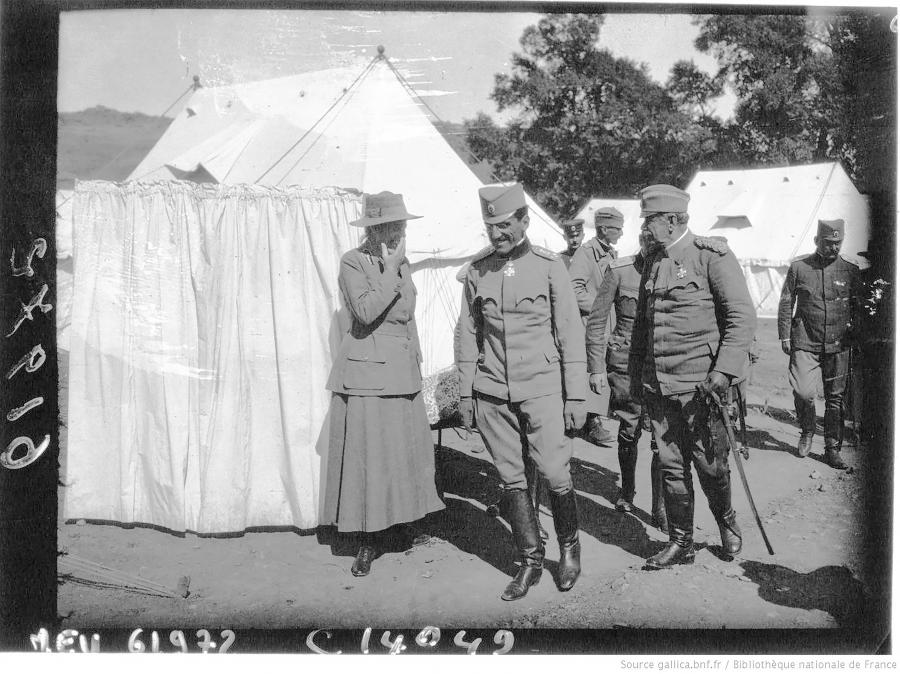

Dr Agnes Bennett, Chief Medical Officer of the Scottish Women’s Hospital with Crown Prince Aleksandar of Serbia during his visit to the hospital.

Image: Agence Meurisse, Gallica

Australians and New Zealanders in and around Serbia

Australians and New Zealanders served with British Army units and the Royal Flying Corps in Salonika, with a smaller number serving under the auspices of the Australian Imperial Force and the Australian Army Nursing Corps. Civilian volunteers assisted in hospitals and voluntary medical units attached to the Serbian Army as doctors, nurses, orderlies, and ambulance drivers. British Red Cross, the Serbian Relief Fund, the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, Wounded Allies Relief, and similar organisations sent volunteers to Serbia and Salonika to assist Serbia’s war effort.

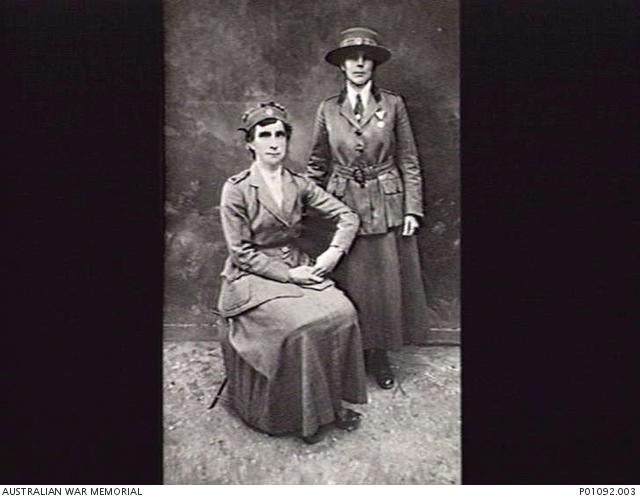

Sister Edith MacKay (on right) wearing her Serbian Medal for Zealous Service. 1919.

More information

Military Involvement

Several hundred Australians and New Zealanders served alongside the Serbian Army on the Salonika Front from 1915 to 1918. Some served with the British Army, mainly as officers in the infantry and artillery, or with medical units; others served with the Royal Flying Corps. Small units of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) were also engaged alongside British forces. A large number of Australian Army nurses served in the theatre. A number of Serbs and other Slavs living in Australia during the war were recruited and partially trained by the Australian Army for service with the Serbian Army. At least 67 Australians and New Zealanders were killed and wounded in the fighting. Because of the disparate nature of the service of Australians in the different military forces, more are likely to be identified in future.

British Army

Some 145 to 165 Australians have been identified to date as having served with British Army units on the Salonika Front. Eleven Australians have been identified to date as serving with the 10th British Division; some had joined the AIF and transferred to the British Army, others joined British units in England, and two were attached to the division from the AIF. In December 1915 the 10th Division was attacked by Bulgarian forces at its defensive positions on a ridge above the village of Kosturino. Over several days of fighting the British troops were forced to withdraw. Australian Lieutenant Ralph Cullen was killed on a position called Rocky Knoll in front of the main British positions.

John Paterson from Perth served with one of 11 ASC Mechanical (Motor) Transport companies working with the Serbian Army. His unit, a light supply and ammunition column unit, the 706 company, used Ford small trucks to carry supplies to the Serbian front lines. Each of these companies had 130 trucks, which carried about 250 kilograms of load. Other companies had heavy trucks — “Albions”— carrying usually one ton and one half rather than the three-ton rated capacity. The heavy companies were tasked with carrying supplies forward from the railheads, while the light Fords were tasked with delivering as far forward to the Serbian front line as possible. From that point the Serbian infantry and artillery carried supplies forward by pack animal. John Paterson died from influenza in October 1918 and is buried in Skoplje.

Serbian Army

The Serbian Army suffered tremendous casualties in the war and the need to find replacements was acute. As Serbia was occupied from late 1915, there was a lack of access to a home population from which to recruit. Allied Supreme Commander General Joffre asked countries including Australia to recruit Serbs and other South Slavs to join the Serbian Army at Salonika. In Australia, 88 men volunteered, passed the medical examination, and were taken to Liverpool Military Camp. Lieutenant Colonel James Walker DSO, VD—recently placed on the Reserve of Officers and previously Commanding Officer of the 25th Battalion—was given a small staff and put in charge of training the men and taking them to Salonika. The men arrived in Salonika in October 1917, at which point Colonel Walker handed the men over to the Serbian Army, where they were issued with Serbian Army uniforms and equipment. Each man was paired with an experienced Serbian soldier who would guide them through their training for the Serbian Army before they were posted to various companies of the 11th Infantry Regiment of the Serbian Army. These men took part in the September 1918 offensive that broke through enemy lines. Some were sent to Albania to fight Austro–Hungarian troops stationed there. It is known that at least one of them was killed. After the war, some returned to Australia.

Balkans, Greece. c. 1918. Two wounded Serbian Army soldiers being brought down from the mountains on seats on each side of a led mule. (Donor British Official Photograph SAL765)

More information

Australian Imperial Force

Among the different Australians in Salonika at various times was a 53-man platoon of the 6th Australian Infantry Brigade, comprised of drivers from the 22nd and 24th Battalions, commanded by Lieutenant William Merriman Trew from Victoria. It was sent to Salonika in October 1915, just as the Central Powers commenced their invasion of Serbia. Trew’s platoon assisted British troops preparing for the move into Serbia by buying and assembling pack animals for use in the mountainous terrain. In October 1915 the unit moved with the British 10th Division from Gallipoli into Serbia to provide flank protection for French forces that had advanced further north into Serbia. The drivers provided pack animal transport for ammunition, rations, and stores, and evacuated casualties for the forward units which took defensive position on the Serbian–Bulgarian border near the village of Kosturino. The drivers also acted as a security detail for headquarters and were guards for Bulgarian prisoners. Six of the 53 members of this unit have been identified to date.

As allied forces settled at Salonika, the demand for pack animals increased. In August 1916, Captain James William Boyes of the 1st Australian Remount Unit was ordered to arrange the transport of 600 mules from Egypt to Salonika. The mules were loaded successfully and the unit sailed to Salonika. Boyes handed the mules successfully to the allied armies and the pack animals performed a vital task in supply and medical evacuations in the often-muddy and difficult terrain.

Australian Artillery men firing their Howitzer on the Salonika front.

A03457

Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) had squadrons stationed near the front line, with its aircraft being primarily used for reconnaissance and some bombing operations. Several Australians and New Zealanders served with the RFC in this theatre as air and ground crew.

In March 1917, two squadrons of the RFC carried out a bombing raid on Hudova airfield in Serbia. Aircraft were not equipped with sophisticated bomb-dropping or aiming equipment, and during the operation, Australian 2/Lieutenant Donald Glasson of 47 Squadron was flying a two-seater Armstrong Whitworth F.K.3 without an observer in order to fit more bombs into his aircraft. He was last seen flying low over the airfield closely pursued by a German plane. Later that day, German aeroplanes bombed the Yanesh airfield and dropped a note saying that Glasson had been shot through the stomach and died. He was buried at Skoplje cemetery in Serbia.

First to arrive – health services

The first Antipodeans to arrive in Serbia during the First World War were Australian Dr Thomas Alexander Benbow and Australian-born New Zealander Nursing Sister Emily Jane Peter. Both arrived in November 1914 with charitable organisations, Benbow with the British Red Cross and Peter with the Serbian Relief Fund Mission. Other Australian and New Zealand doctors, nurses, orderlies and ambulance drivers followed with other missions, most of which established hospitals in premises provided by the Serbian medical authorities or came equipped as tented mobile hospitals able to move with the Serbian Army as required. Foreign medical missions were used by the Serbs to treat soldiers wounded during heavy fighting with the invading Austro-Hungarian armies. Many foreign medical missions would later help the overwhelmed Serbian medical services to deal with the typhus epidemic.

Following the invasion of October 1915, early medical volunteers in Serbia were faced with the difficult decision of whether to leave while there was still time, or stay and face the prospect of capture. Male members of staff were advised to leave as they would be unlikely to be released by the enemy, while female staff had a reasonable chance of being repatriated. Several Australians and New Zealanders elected to stay on duty at their hospitals and were captured by the invading enemy armies.

Mabel Atkinson and Katherine Coleman were captured while serving with the Serbian Relief Fund in Skopje. They were released after some months and sent to Russia, where they reached Scandinavia and England. Ethel Gillingham, Clara Morris, and Lucy Ryan were captured with the British Red Cross in Vrnjacka Banja. Catherine Hall, Laura and Charles Hope, and Jessie Ann Scott were captured while serving with Scottish Women’s Hospitals at Vrnjacka Banja. Australians and New Zealanders with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals and British Red Cross units in Vrnjacka Banja were released in February 1916 via Switzerland and returned to England. Laura Hope wrote a diary of her experiences which is now in the keeping of the Library of South Australia.

Australian Army Nursing Corps

In April 1917, the British Government asked Australia to send nurses to staff four 1,040-bed British General Hospitals on the Salonika Front; using Australian resources in Egypt, Palestine, and on the Salonika Front was considered more economical and convenient than supplying resources from Britain. The Australian Defence Department agreed to send Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) nurses. The first contingent of Australian nurses arrived in Salonika in mid-1917, with a second contingent arriving the following year. It is estimated that 340–390 AANS nurses served on the Salonika Front.

The AANS nurses were led by Principal Matron Mrs Jessie McHardy White from Yarra Glen, Victoria. After training at the Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, White ran a private hospital in Melbourne and was a member of the Australian Army Nursing Service Reserve in the years before the war. She volunteered for service in October 1914 and left Australia with the first contingent of the AIF. By 1916 she had been promoted to principal matron of the AIF in England, but later left for Australia. She was made principal matron in charge of the first contingent of 364 Australian nurses to go to Salonika, and would take on the role of matron of No. 1 Unit at Hortiach. Jessie White was appointed a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Mentioned in Dispatches, and awarded the Greek Medal for Military Merit and the Serbian Order of St Sava in recognition of her work at Salonika. She returned to Australia in June 1919.

Olive May (Kelso) King, In the uniform of an ambulance driver, Serbian Army. She wears, left to right, the Serbian Order of St Sava, 3rd Class; the Serbian Medal for Bravery, Silver;, and the Serbian Medal for Zealous Service”

More information

The Naval Effort

Six Australian torpedo boat destroyers and about 400 Australian sailors supported the campaign in the Adriatic, Aegean, and Mediterranean Seas in 1917–18. The small Australian flotilla, serving as part of the British Navy, was under command of Commander William “Cocky” Warren on board the HMAS Parramatta. It was mainly engaged in implementing an anti-submarine barrage across the straights of Otranto against German and Austro–Hungarian submarines operating from bases in the Adriatic Sea. Some ships participated in the bombing of Drač (or “Durazzo”) port in the Adriatic as part of the allied offensive which broke through the enemy front and enabled the Serbian Army to liberate the rest of Serbia in 1918. As well as conducting naval operations in the Adriatic Sea, the Australian ships played a significant role in securing safe passage of troops and supplies bound for Salonika. One sailor was lost at sea and a number died from influenza at the end of the war. Commander Warren was accidently drowned.

Part of the British deployment to Salonika in October 1915 included the 1st New Zealand Stationary Hospital. When SS Marquette, which was carrying the staff and stores, was torpedoed in the Gulf of Salonika on 23 October 1915, 167 lives were lost, including 32 New Zealand nationals.

Australian officer Leonard Cooper, who had just been commissioned in the British Army, was also lost at sea.

Australian Navy torpedo boat destroyers at anchor at Brindisi.

Dr Mary de Garis with a Serbian officer at the Scottish Women’s Hospital at Ostrovo. Mary was decorated by Serbia for her service with the Order of St Sava. Glasgow City Achives, TD1734/19/2

Australians and New Zealanders Decorated by Serbia

In gratitude to those who came to its aid during the First World War, the Serbian Government decorated a number of non-Serbian nationals, including Australians and New Zealanders. To date, 154 Australians and New Zealanders decorated by Serbia have been identified. Some, including Olive King and Agnes Bennett, were given awards by the government itself. However, the Serbian Government also gave a number of medals to the Australian Imperial Force to be granted by Australian authorities. For example, Lance Corporal Hubert de Vere Alexander of the 4th Field Company, Australian Engineers served on Gallipoli for the duration of the campaign, and was later awarded a Serbian Gold Medal. He went on to serve in France and was killed by artillery fire while surveying a light railway on the Somme in August 1918.

Lieutenant-Colonel Stan Watson CBE DSO MC ED (ret’d), wearing his Serbian Order of the White Eagle with Swords on the extreme right, photographed on King William Street in Adelaide, South Australia on Anzac Day 1980.

Some of the first honours bestowed on Australians for bravery and distinguished service at Gallipoli were Serbian Orders and Medals. The Serbian decorations were awarded by the Serbian King but the choice of recipients was made by the Australian Imperial Force. The Australians so decorated often wore these Serbian orders and medals for many years after the war.(Major Paul A Rosenzweig OAM JP (ret'd)

General Sir Philip W Chetwode KCMG, decorating an Australian officer with the Order of the White Eagle.1916.

Further details about the service of Australians and New Zealanders relating to Serbia are given in

Our forgotten volunteers: Australians and New Zealanders with Serbs in World War One,

and

Serbian decorations through history and Serbian medals awarded to Australians.

Banner image: H04747

The Crown Prince Aleksandar of Serbia and Field Marshal Voivoda Misic at an observation post Le Boue on the Serbian Front.