Australian Prisoners of the Germans and Italians

Most Australians have heard of the shocking stories of Australian prisoners of war of the Japanese during the Second World War. But few will be aware that some 7,000 Australian soldiers became prisoners of war of the Germans and Italians, the majority captured during the ill-fated Greece and Crete campaigns of April to June 1941. Perhaps because of the focus on the cruelty and mistreatment suffered under the Japanese, the stories of hardships, deprivation and survival of the prisoners under the Germans and Italians have not received the attention they deserve.

The Australian War Memorial has begun a program to ensure that information regarding this aspect of our military history is available to the public. A key part of this is the process of transcribing data on prisoner of war cards maintained by Australian Imperial Force Headquarters throughout the war. These cards record personal details, details of place and date of capture (where known), and notifications by the Red Cross, the Vatican and other sources as to the whereabouts and health of each prisoner. The German authorities were particularly meticulous in recording and reporting prisoner of war movements between camps and other personal events, even as the end of the war in Europe approached during the chaotic months of mid-1945.

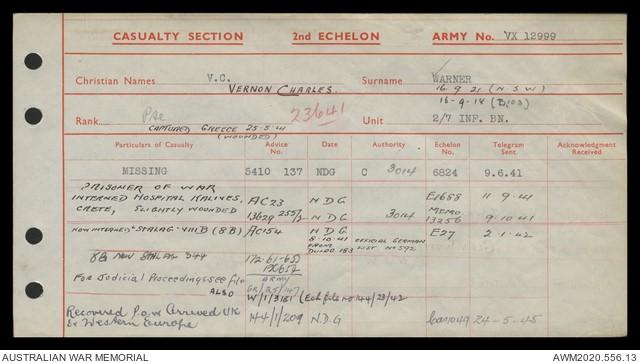

POW card of Pte V C (Charlie) Warner, 2/7th Inf Bn

Transcribing information from the prisoner of war data cards into searchable databases has been completed by a team of volunteers and AWM staff. I was part of that team.

Transcribing can be a somewhat tedious task, but I found that I was regularly distracted by seemingly minor coincidences or apparent inconsistencies. My curiosity led me to investigate many of these, often distracting me for hours, but making the data entry process more interesting and rewarding.

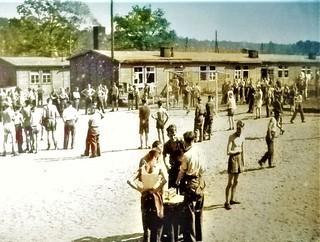

As I worked through the cards, I noticed that many Australian prisoners of war who were recorded as being in the Italian “Prigionieri di Guerra Campo 106” (Prisoner of War Camp 106) in mid-1943 were next reported to have arrived in Switzerland, and to be repatriated back to Australia in late 1944. My research showed that Campo 106, in northern Italy, was not a prison in the traditional sense, but a cluster of work farm camps where prisoners were put to work in the surrounding rice fields. The prisoners were guarded by the Italian army but not as rigorously as at some other camps across Italy or Germany.

Australian and NZ POWs at a Camp 106 work farm with an Italian Guard (L) 1943. (Photo: aifpow.com)

On 8 September 1943, news broke that Italy had formally surrendered to the Allies, with a secretly negotiated armistice agreement which included provision for the handing over of Allied prisoners in Italy. The War Office in London sent messages to the numerous camps that prisoners of war were to “stay put” pending the arrival of Allied forces. German authorities, of course, were not party to this agreement and had no intention of leaving Italy, nor of allowing all those prisoners to be released to roam behind their lines. Several days of confusion followed before the German Army could move in to secure all the camps across Italy. In some camps pro-Fascist commandants or the senior Allied prisoner of war enforced the stay put order; in others the Italian guards just opened the gates and left, leaving the prisoners temporarily unguarded.

This is what happened in Campo 106, allowing the prisoners of war, including many Australians, to leave and move south towards the advancing Allied forces or north to the Swiss border. Prisoner of War record cards indicate that about half of the prisoners in Campo 106 were able to make good their escape, most into Switzerland. Some died in the effort to escape, while the remainder were rounded up by the Germans and returned to captivity.

It is estimated that about 17,000 of the 70,000 Allied prisoners of war in Italy escaped from various camps during this period, including some 500 Australians. But at least 50,000 prisoners were transferred to Germany to endure another two years as prisoners of war. Much has been written of the failure by Allied commanders to plan adequately for the security of those prisoners or to take account of the inevitable German response.

Another apparent coincidence which caught my attention was the number of prisoners of war named Warner who came from Tumbarumba in New South Wales. Checking Department of Veterans’ Affairs rolls and cross-checking next of kin revealed that five of them were brothers: William “Bill” Warner, aged 34 (shearer), Alfred “Andy” Warner 28 (station hand), Ernest “Bunny” Warner 30 (horse trainer), John “Ninety” Warner 24 (station hand) and Vernon “Charlie” Warner 19 (station hand). Unfortunately, the records don’t explain how they got their nicknames! They enlisted soon after the war started and completed training at Puckapunyal. Together they embarked for the Middle East in September 1940 and joined the 2/7th Infantry Battalion of the 6th Division.

L-R: Andy, Bill, Charlie, Bunny and Ninety Warner at their farewell in Tumbarumba, August 1940

(Photo: Australian Women’s Weekly)

In April 1941 their battalion, along with most of the 6th Division, was sent to Greece to defend against an expected German invasion. For the next two months, they fought a series of withdrawals and rear-guard actions across Greece and then on Crete. The 2/7th fought a final rear-guard action on 30 May 1941 which allowed the rest of the Allied force to be withdrawn from Crete, but resulted in most of the battalion being left behind and captured.

The prisoner of war cards show that Charlie Warner had been wounded in action and captured in Greece on 25 May 1941, while the other brothers made it to Crete where they were captured the following week. They were processed by the German authorities through different transit camps, with Charlie spending time in a military hospital for treatment of his wounds. They were all eventually re-united in Stalag VIIIB, near Lamsdorf in eastern Germany (now Lambinowice in modern-day Poland) where they spent the remainder of the war together. Stalag VIIIB (renamed Stalag 344 in December 1943) was a notoriously harsh camp. The weather was cold, there was limited food and working conditions in the coal mines and factories were harsh.

Stalag VIIIB – Lamsdorf (Photo: powmemorialmuseum@outlook.com)

In January 1945, as the Soviet army approached, camps were evacuated and the prisoners were forced to march westward in a harsh European winter, poorly clothed, with little food and often sleeping at night in the open. Many died on the march, but the Warners managed to survive, and were liberated by advancing American forces in March 1945. They were then repatriated to England in May 1945 before returning to Australia later that year.

The story of the Warners received considerable press coverage at the time, with a Women’s Weekly article in July 1941 focusing on their enlistment, a farewell party before they left, and the family they left behind. The article is typical of the cheerful, positive stories being published during the war. News of their capture, and later their safe release in 1945, also received coverage in local and national papers.

The five brothers weren’t the only Warners from Tumbarumba. Three of their cousins also enlisted: James Warner also enlisted, serving with the 2/4 Field Squadron RAE, Arthur Warner joined the RAAF and Olive Warner joined the Australian Army Women’s Medical Services. This was a significant contribution from a small country town.

The happy ending to this story is that all eight Warners survived the war and returned to Tumbarumba to resume their lives. Some appear to have moved on to other places, but some of their relatives and descendants are still living in the area.

Data entry and uploading of the 7,000 prisoner of war cards is complete and is available to be searched in Series AWM402 on the Australian War Memorial website Middle East - Recovered Prisoners of War (POW), Rolls, 1939-45 War | Australian War Memorial (awm.gov.au).

Further Reading: Escape from Campo 106

Beckingsale, M. “The Five Fighting Warners” Women’s Weekly, 26 Jul 41, available at https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/47486336?searchTerm=Warners%20of%20Tumbarumba

Carver, T. “The Blunder that Doomed 50,000 British Prisoners”, The Observer, 1 Nov 09, reprinted in https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/nov/01/second-world-war-british-pows

Kittel, K. “Shooting through: Campo 106 escaped POWs after the Italian Armistice”, Echo Books, Canberra 2019.

Mason, W. W. “Prisoners of War” in The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945, http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-WH2Pris-_N89858.html

Further Reading: The Warner Brothers

“Stalag VIIIB/344 The Long March”. Available at: https://www.prisonersofwarmuseum.com/lamsdorf-long-march.html

Mylne, L. “Return to Hell Camp Stalag VIIIB”, in The Weekend Australian Magazine, 21 April 2018. Available at: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/weekend-australian-magazine/daughters-pilgrimage-to-stalag-viiib/news-story/976f4b4176c2c3bf52465cb59bdd2ae8

Monteath, P. P.O.W.: Australian Prisoners of War in Hitler’s Reich, Macmillan Australia, 2011.