Bandsmen of Bapaume

The Band of the 5th Australian Infantry Brigade, led by Bandmaster Sergeant A Peagam of the 19th Battalion, passing through the Grande Place (Town Square) of Bapaume, playing the Victoria March. The ruins of the town are still smouldering, and smoke rises from the debris of surrounding buildings. A few miles away, on the Lagnicourt-Noreuil line, the fighting continues.

“Australian bandsmen, playing triumphal airs, marched through the blazing streets and burning ruins, indifferent to the perils of fire and shell and burning buildings, cheerfully confident in their sense of victory.” (The Ballarat Star, 10 April 1917)

In the early Spring of 1917, after a weary winter of almost unbearable trench duty on the Somme, German forces began to retire from the battlefield and strategically withdraw to the Hindenburg Line. The allied troops advanced on their heels, and the Australians soon burst through German defences to occupy the French town of Bapaume on 17 March 1917.

The troops entered a devastated town. The retreating Germans had methodically razed Bapaume in their wake; houses were pillaged and lay smouldering, and the streets were still aflame with burning buildings and obstructed by ruins and rubble.

“From the top of the knoll Bapaume lay beneath our feet, burning… half obliterated by the dense white smoke, we could see the burning roof beams of tall houses. Further still rose faintly through the smoke the square stone tower of the Town Hall. Every minute two or three heavy shells crashed into the town, flinging up great dense bursts of black smoke, or of red brick dust, and every now and then tossing to the sky fragments of wall or loot as a terrier tosses a rat. Bapaume was having a terrible time this afternoon.” (CEW Bean, Dispatch on March 17, Sydney Mail)

Australians of the 30th Battalion making their way along a street of burning ruins in Bapaume, the day of its occupation by our troops.

Soldiers on horseback passing through the wreckage in the Rue de Peronne at Bapaume.

Yet the day after the capture of Bapaume, in stark contrast to the tragedy of the ravaged town, strains of lively music could be heard floating through the air. The triumphant bandsmen of the 5th Australian Infantry Brigade Band marched heroically through the burning streets. Their “Victoria March” reflected the jubilance of the triumphant troops who now occupied the town.

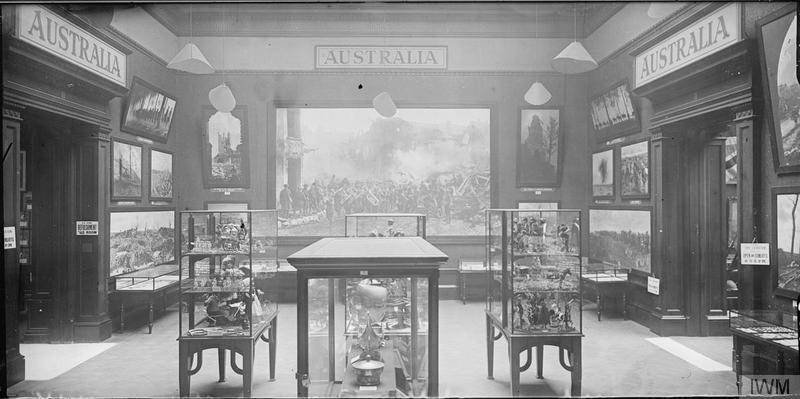

The photograph became one of the most publicised of the First World War, and was said to reflect the characteristic fighting spirit that animated the Australian troops in the dramatic events of the period. The photograph was published widely in Australian newspapers, and featured prominently in a major exhibition mounted at the Royal Academy of the Arts in London during 1918. The “Imperial War Exhibition” featured a gallery of Australian official photographs and war relics, including an enlarged print of the Bapaume photograph, which was displayed grandly as the visual centrepiece of the Australian gallery.

The Australian section of the Imperial War Exhibition at Burlington House, Royal Academy of Arts, under the auspices of the Imperial War Museum, London, 1918. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, Q 30499.

Newspaper articles of the time proclaimed the photograph as an “historic picture” and “one of the greatest battle pictures ever known.” Several newspapers attributed the image to Wilkins, who had selected the photographic content for the exhibition whilst Hurley was in Palestine.

The Band of the 5th Australian Infantry Brigade was comprised of musicians from the 17th, 18th and 19th Battalions. The Bandmaster was 716 Sergeant (Sgt) Albert John Peagam, a 32 year old Foreman Printer for the Bundaberg Guardian. Sgt. Peagam described the band’s march into Bapaume that day in a letter home to his wife, Margaret:

“Our brigade was well to the fore in this great advance, and the day after Bapaume was captured my band entered the town and played through some of its streets. The town was burning when we entered and when we left nine days later it was still burning. The buildings were all blown down and very few were left standing… Moving pictures were taken of us as we were playing through the streets, so if you see any such you will know it is us. We feel it was an honour to be the first band there. Nine days later when we were going back for a rest with the brigade, we passed half-a-dozen bands and they thought they were the first on the scene, but their lips dropped when they saw us going back.” (Bandmaster Sgt. Albert J. Peagam, Letter 9 April 1917)

The film footage that Sgt. Peagam mentions may have been filmed by Wilkins himself, who captured footage he later compiled into a film, Bapaume to Bullecourt, a rare record of the Australians entering Bapaume to pursue the German troops as they withdrew to the Hindenburg Line. At approximately the 9 minute mark in the film, there is a silent clip of “An Australian Band Playing in the Square at Bapaume” which features the 5th Infantry Brigade Band marching through the smouldering town square. Crowds of soldiers mill around to sight the cheerful spectacle.

Despite the fact the Germans had deserted the town, the danger was far from over. Bapaume was littered with bombs. The Germans had hoped that the Town Hall adjacent to the square would be used as a headquarters, and planted a delayed action mine before deserting the town. It was from the vantage point of the Town Hall that the Bapaume Band photograph was captured, and both the band and photographer were lucky to escape the dramatic explosion of this grand building. When the bomb eventually detonated, approximately 30 men who were billeted in the building were buried in the rubble – only six emerged with their lives.

“The Town Hall and several other places were left standing, but they all had mines laid in them and were set off by means of either a slow fuse or an 8 day clock contrivance. The Town Hall was a very big building, and it was blown up by these means, and many men who were billeted in the building, also some officers, were buried by the explosion. We gave programmes in the square opposite this building every afternoon, so consider the band and myself lucky we were not there when it was blown up. The hour when the explosion took place was about 11:30pm, and we were all in bed asleep. The ground rocked and we were billeted about 200 yards away from the scene – all sorts of debris were flung about us. The building was about the size of the Melbourne Post Office, and walls and all were levelled to the ground.” (Bandmaster Sgt. Albert J. Peagam, Letter 9 April 1917)

For the allied troops, who had held the trenches in the Bapaume area throughout the bleak winter of 1916, the capture of Bapaume had signalled a turning point – a farewell to the frozen battleground of the Somme and a new spirit of hope, inspired by the green countryside before them.

“We had put off the Somme battlefield as a man takes off a muddy coat. Before us the same shallow depression that contains Bapaume sloped away to the undulations on the horizon, the gently green sides of it gradually widening. It was an open, green, grassy country, with a few distant clusters of trees round the far scattered villages… it is the men who fought through Bapaume this morning that have finally cleared the Somme battlefield and closed the Somme battle.” (CEW Bean, Dispatch on March 17, Sydney Mail)

The Bandsmen of Bapaume went on to serve in some of the major battles on the Front; the second Bullecourt (3-4 May) in France, Menin Road (20-22 September) and Poelcappelle (9-10 October) in Belgium before the major German Spring offensive of 1918 where they fought some of the Australians’ most legendary battles; Amiens on 8 August, and the attack on Mont St Quentin on 31 August 1918.