Banjo Paterson’s Egyptian publications

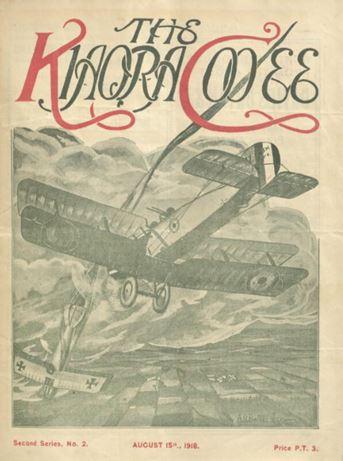

The Kia Ora coo-ee magazine was a troopship serial published by Sphinx Press, an independent publisher working out of the AIF headquarters in Cairo throughout 1918. Soldiers would submit their pieces and an editorial board would review them before inclusion into that month’s edition.

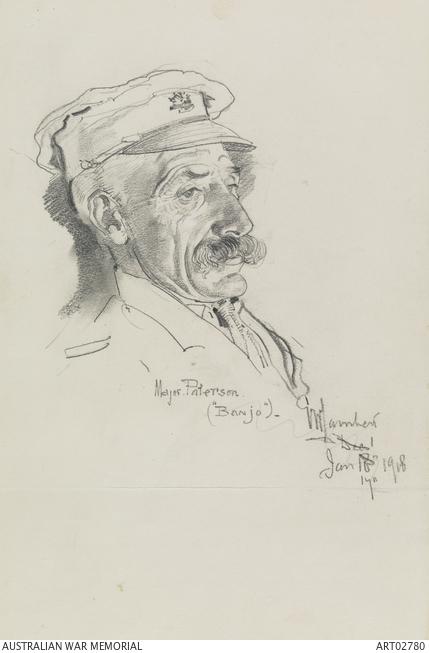

Probably the most well-known contributor was Major A.B. “Banjo” Paterson – somewhat of a celebrity journalist of the day, and today remembered for his works such as Waltzing Matilda and The man from Snowy River. The first issue came out on 15 March, with one issue per month being printed until December 1918; ten issues in total.

George Lambert, Major Andrew Barton “Banjo” Paterson, 17 January 1918, pencil on paper, 30.4 x 19cm, Australian War Memorial, ART02780, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C176387.

The Kia Ora Coo-ee was “issued jointly for Australian and New Zealand troops” and aimed to “gather and dispense all interesting information concerning the different units in Egypt, Palestine, [Thessaloniki] and Mesopotamia”. It was a magazine that brought readers the “real news”. This was frequently written as satire, but always with an underlying element of truth. The magazine contains stories and exposés of minor wartime events that the troops themselves may have discussed, but which were not covered by official news. It contains vaguely raunchy stories about nurses in war hospitals, information about how to identify different Egyptian snakes, unique takes on and interpretations of Middle-Eastern culture, humorous conversations that had been overheard, sporting results (particularly amateur boxing), odes to lost friends, and even a regular letter from a lady in Australia or New Zealand wishing the soldiers well.

Perhaps just as interesting as the articles are the advertisements and the satirical illustrations, often illustrated with exaggerated features, but also with great attention to detail. The cover of the August issue, for example, shows planes in a dogfight that can be easily identified as a German Albatross being downed by an Allied Bristol F2.B.

A.R. Belleridge, Cover: The Kia Ora coo-ee, August 1918, print, Australian War Memorial, LIB108015, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/LIB108015

Paterson wrote four pieces for The Kia Ora coo-ee: a poem, and three “Army sketches” – witty descriptions and anecdotes about different incidents similar to those encountered by soldiers and nurses.

Paterson’s first entry was a poem written for the May issue, titled Moving On:

In this war we’re always moving on,

Moving on;

When we make a friend another friend has gone;

Should a woman’s kindly face

Make us welcome for a space,

Then its boot and saddle, boys, we’re

Moving on.

In the hospitals they’re moving,

Moving on;

They’re here today, tomorrow they are gone;

When the bravest and the best

Of the boys you know “go west”,

Then you’re choking down your tears and

Moving on.

This poem differs from the magazine’s upbeat and often satirical tone in order to address the issue of grief and loss, and the way in which the narrator and soldiers like him are forced to deal with death. The rapidity through which loss occurs is highlighted by the repetition of the second line (“moving on”). While death is never explicitly mentioned, it is implied by the use of the euphemistic slang term “go west”.

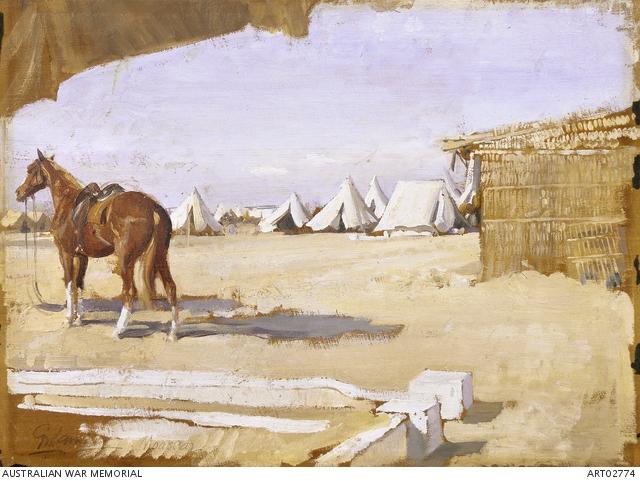

George Lambert, Moascar, from Major “Banjo” Paterson’s Tent, 15–17 January 1918, oil on wood panel, 29.6 x 37.2cm, Australian War Memorial, ART02774. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C172143?image=1

Paterson’s other submissions to the magazine are far more upbeat and highlight his mastery of capturing the humorous essence of a situation. The army sketches were published in the last three issues of the magazine (October to December).

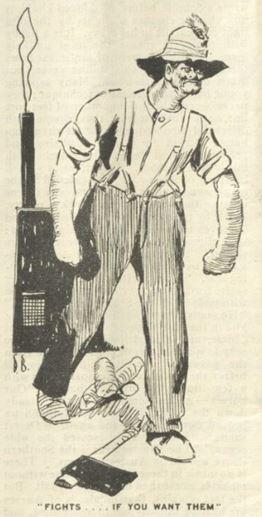

The first is entitled “The cook-house”. Paterson starts out by describing the cook-house and the soldiers working there, before rounding out the sketch with an anecdotal tale. Likened to a Greek tragedy by Paterson, the cook-house has a staff of four: the cook, a tired old soldier too old for the front line; his offsider and protagonist of the story, Donnelly; and two assistants. While the cook is too old and passive for the day-to-day life, Donnelly, like the “Delphic oracle,” is the source of wisdom, the best fighter, and resolver of disputes. His assistants are likened to a Greek chorus – simply having “thinking roles”, they sit and observe and occasionally belt out a piece of wisdom. The story tells of a soldier, Bluey, who wanted hot water that he was not entitled to and his subsequently ejection from the cook-house by Donnelly. The story ends with the cook showing that he too is not to be messed with, giving a disrespectful officer a meagre portion of “ungyuns”. The tale gives an insight into the power dynamic of the cook-house, where rank means little; the cook and his staff are, in fact, presented as being among the most important and powerful people in camp.

David Barker, Donnelly, The Kia Ora coo-ee, October, p. 2, 1918, print, Australian War Memorial, LIB108015, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/LIB108015.

To highlight the importance of army cooks, in the second of the army sketches, entitled “A general inspection”, Paterson discusses the inspection of the cook-house. In doing so he demonstrates, once again, how it is a force to be reckoned with. Paterson even suggests that “No cook, no company” should be a “[m]ilitary maxim to be elaborated in lectures at Duntroon”. Presented in the first person, this story elaborates on how the cook is forced to lie to the general in order to please him, as the general will always find some form of fault.

The final army sketch is a sombre tale of a signaller in hospital after being shot in the head. Paterson starts by describing the hospital (“a Kantara landmark”) and the nurse looking after the soldier, and concludes with a first person account of the signaller’s final moments. After explaining the nurse’s dedication to her job and how death continues to affect her, despite being around it every day, the narrative turns to the camaraderie of the fellow “brother Diggers” as the signaller reverts to his training, trying to signal his comrades that are no longer there. Once the signaller spots a “small piece of green tent lining fluttering at the door” that he thinks is his company signalling back to report that they are alright, he calms down “[a]nd a few seconds later the signaller marched out”. Once again, Paterson alludes to death without using the word. It is something he seems to actively avoid – perhaps a result of his constant “moving on”.

Unknown artist, A Kantara Landmark, The Kia Ora coo-ee, December, p. 8, 1918, Australian War Memorial, LIB108015, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/LIB108015.

Paterson displays incredible skill in capturing the diction of soldiers. When quoting the company cook in the first of the army sketches, he writes “[h]e says you wouldn’t cook for shearers! You that was voted in as cook seven years runnin’ in the biggest shed in Queensland, with two hundred shearers! Wasn’t you, Donnelley?” When quoting a Scottish soldier in the second edition, he writes “[w]ha the deuce keers whit happens tae a kuk?” In his manipulation of spelling, Paterson captures the essence of the character, with no mistaking their countries of origin, and allows the reader to gain a most vivid picture of the scenes Paterson is painting through his words.

Paterson’s works addressed here are, true to style of The Kia Ora coo-ee, regular stories and anecdotes about the everyday life that Paterson experienced. They are not pretty, nor glamourous, but address everyday events facing soldiers, from dealing with death and grief to the importance of the cook-house. It is, to the soldiers on the ground, the real news.

The Australian War Memorial holds copies of The Kia Ora coo-ee (https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/LIB108015) as well as original drafts of Paterson’s first two army sketches (https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C247112). Digitised copies of the The Kia Ora coo-ee can be found on the National Library of Australia’s website (http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-8327183)