The Battle of the Samichon River - the Hook 24 - 26 July 1953

This month marks the 70th anniversary of the armistice that ended the Korean War. In the three days leading up to the cease-fire, a savage battle was fought in the hills of the Jamestown Line at a position known as the Hook.

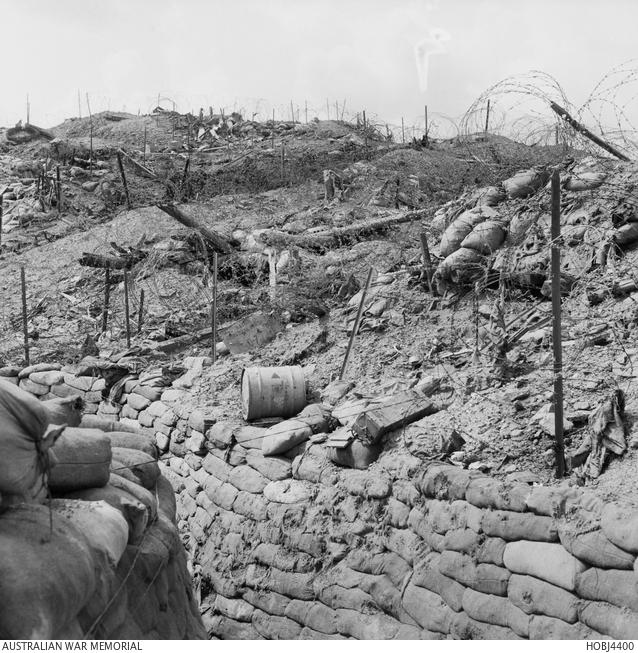

Heavily damaged trenches on the Hook, 13 July 1953.

The Chinese People’s Volunteer Army made a last-ditch attempt to wrest strategically important territory from United Nations forces before the armistice was signed. Their attack, which began on the evening of 24 July 1953, fell against positions on the Hook that were held by the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (2RAR), and on American positions to their left, held by the 7th Regiment, 1st Division of the United States Marine Corps.

As evening deepened into darkness on 24 July, parties of Chinese infantry began to probe the Australian positions on the Hook. Each of these probes was detected and engaged by the Australians. Just before 9 pm, Chinese artillery opened fire on the Australian and American positions, after which a ground assault was sent against the Australians at Hill 121 and the Marines’ positions at Hill 111, as well as positions further to the left such as Boulder City. Also stationed on Hill 111 was a section from 2RAR’s medium machine-gun platoon, under the command of Sergeant Brian Cooper. These men were tasked with providing fire support to the left forward company (C Company, 2RAR) on the Hook.

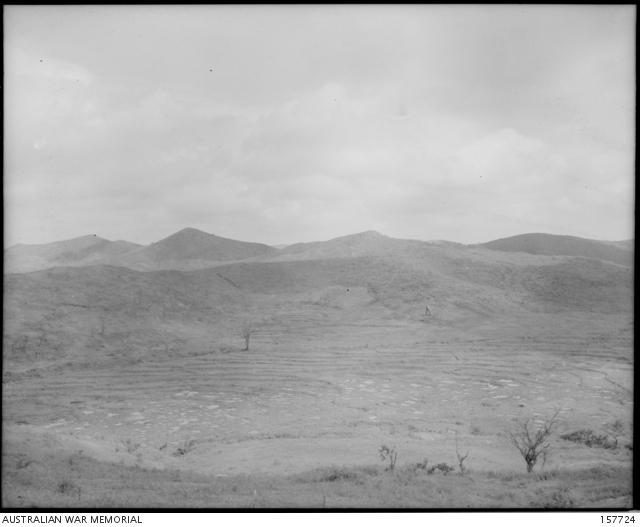

The results of supporting fire supplied by New Zealand gunners of 16 Field Battery, RNZA. These water filled shell holes are in front of C Company, 2RAR’s positions on Hill 121, near the Hook.

Hill 111 and the Marines’ main line suffered repeated artillery barrages and Chinese infantry wave attacks. Several of the Marines’ forward trenches were taken and the positions on Hill 111 were only saved when Sergeant Cooper called down artillery onto his own position. The attacks finally petered out in the early hours of 25 July. When Cooper looked out from his position that morning, he saw many Chinese dead to his front, and the valley below littered with Chinese bodies.

The Chinese 137th Division had suffered heavy casualties, largely due to the New Zealand gunners of 16th Field Regiment, Royal New Zealand Artillery (RNZA). They used variable timing fuses on their shells, which had been set to detonate just above ground height. The devastation of shrapnel on packed ranks of infantry, combined with the defensive fire from Australian and American positions, decimated the Chinese attackers.

The Marines spent much of the day retaking their lost positions, and had only scant time to repair their defenses before dark. The men of 2RAR also repaired as much of their damaged positions as they could before nightfall and the next expected attack by the Chinese.

Throughout the day, Chinese artillery kept up a constant harassing fire on the Australian and Marines’ trenches and wiring, disrupting much of the repair work. At 9 pm the weight of shells being fired at the Australians and Americans intensified, and by 11 pm there were over 30 shells per minute landing on Hill 121 and 2RAR’s mortar position. The Marines’ line was also being heavily shelled.

At 11.15 pm the last Chinese offensive of the war began. Once again the positions on Hill 111 were attacked, along with the Marines’ front-line positions. A bunker between Hills 121 and 111, known as the Contact Bunker, which guarded an access point to Hill 121, was also heavily attacked.

The Contact Bunker, held by Corporal Ken Crockford and six men of C Company, 2RAR, was besieged and a savage hand-to-hand fight ensued. Crockford called down artillery onto his own position, causing many casualties to the attacking Chinese and forcing them to withdraw. The men in the contact bunker were unscathed by the artillery barrage.

Sergeant Cooper on Hill 111 again had to call in artillery onto his position to stop determined Chinese attacks from overrunning his position and those of the Marines nearby. Despite the heavy assaults, the Marines held Boulder City and by mid-morning on 26 July had driven the Chinese out of their front lines, once again restoring their positions.

At 3 am on 26 July, the Chinese senior command called off their offensive. The 137th Division had been smashed by a determined and dogged defence by the men of 2RAR, the 7th Marine Regiment and the artillery of the 1st Commonwealth Division and Marines’ 1st Division.

At 10 am on 27 July the formal armistice was signed at Panmunjom, which took effect at 10 pm that night, thereby ending the Korean War. For the Australians emerging from their bunkers the following morning, the sight of the valley below their positions was one of horror. Between two to three thousand Chinese bodies lay in the valley and around the hard-contested positions of Hill 111, the Contact Bunker, and along the Marines’ line. It was estimated that their wounded would have exceeded 10,000 men. The exact figures are unknown. The men of 2RAR had suffered 5 men killed and 24 wounded. The Marines of the 7th Regiment had suffered 43 men killed and 316 wounded.

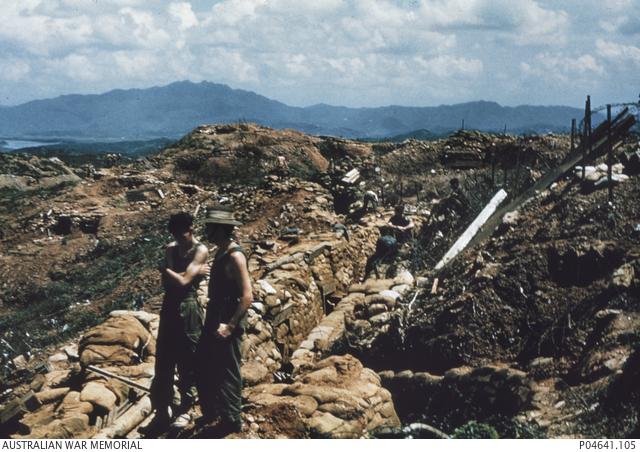

Two unidentified members of 2RAR stand above their front-line positions near the Hook the day after the armistice.

Over the following days, UN and Chinese forces each withdrew two kilometers, with the vacated ground becoming what continues to this day to be the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).

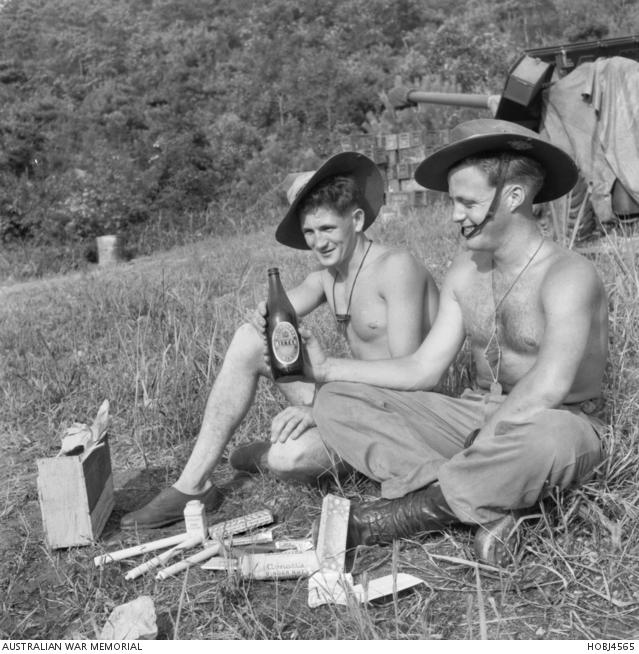

Sergeant Brian Cooper MM (front) and Corporal Ron Walker relax following the armistice. Both men had been involved in the defence of Hill 111.