'This is who I am'

Ben Farinazzo with his wife, Jodie, and their three children, Keely, Tom and Max, at the Memorial.

Ben Farinazzo is a tower of strength. A rower and powerlifter, he won gold for Australia in the indoor rowing at the Invictus Games in Sydney, but it’s his inner strength that shines through as he shares his own personal story in a bid to help others.

“It’s absolutely terrific just to be part of the Invictus Games experience,” he said.

“The ability to connect with an extraordinary group of people who are focused on improving the quality of their lives and the lives of others, despite their wounds, injuries and illnesses, is just outstanding … and to be able to share that with the community is just fabulous.

“These games are about reaching out to Australians and calling on them to celebrate what we call the unconquerable spirit of our wounded veterans and their families, as well as recognising the positive healing power of sport.”

The 44-year-old from Canberra deployed to East Timor in 1999 as part of Interfet, a multinational peacekeeping taskforce, mandated by the United Nations to address the humanitarian and security crisis that took place in East Timor from 1999 to 2000, until the arrival of UN peacekeepers.

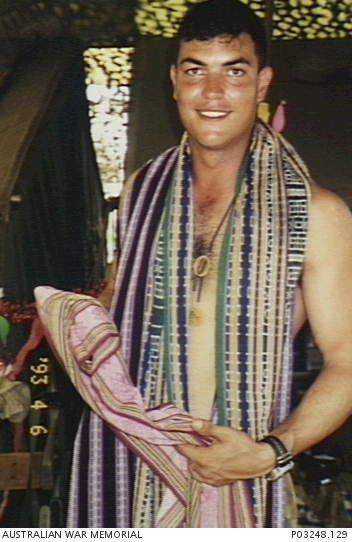

Informal portrait of Captain Ben Farinazzo with the East Timorese weavings he was given as a tribute to him for his help in delivering a baby a few days earlier.

An Indonesian linguist, Farinazzo worked as an interpreter and liaison officer and considers himself “very fortunate” to have been able to work closely with the East Timorese people.

In an interview with the University of New South Wales Canberra, he said his service in East Timor was the highlight of his military career. But it was not without cost.

“East Timor was a tremendous experience, but it also had a number of challenges,” he said.

"It provided an opportunity to put into practice all that I had trained for [and] the ability to communicate directly with the people and share their stories first-hand was a blessing.

"However, it also left deep mental scars that were left untreated and festered over a period of 15 years. It can be hard to comprehend the horrors that humanity can inflict on itself.

“It really affected me … It was such a deep human connection I had with those people, but particularly around the Suai Church massacre.”

The militia had killed up to 200 people who were seeking refuge in the church, and Farinazzo had to help locals, many of them children, find the bodies of their loved ones.

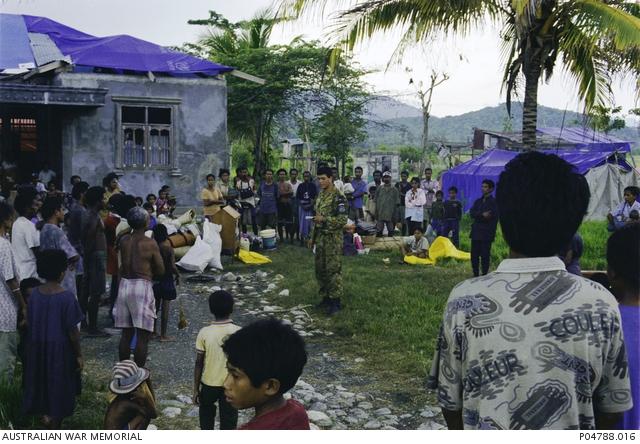

Ben Farinazzo arrives for talks with refugees at a transit centre for displaced persons.

“That had a deep emotional impact on me,” Farinazzo told UNSW Canberra.

“I knew it did at the time, but I didn’t realise the extent to which it had an impact on me. Of course, I came back and bottled it away and got on with my life, but over time that wound continued to fester, to the point where I tried so hard to block those emotions.

“At the same time, you tend to block the other emotions such as joy and happiness, so you don’t feel anything anymore. That led me to a point where I started to consider what life was all about.”

Eventually, his wife found him in the foetal position in the shower, crying out for help, and he spent 12 months in hospital.

“You have all these different strategies that you put in place, but unless you address the root cause of it and seek professional help, it can tear away at you,” he told UNSW. “I tried to beat it and it smashed me pretty hard.”

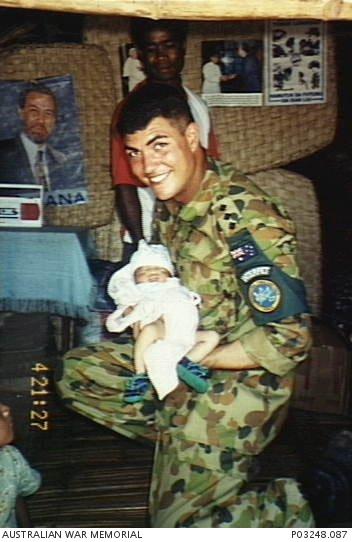

Ben Farinazzo holding "Baby Ben" whom he helped to deliver. The baby's mother and father (standing, background) named the baby after Capt Farinazzo to show their gratitude for his help during the delivery.

He “couldn’t believe it” when he saw a doctor who had served in Rwanda and she diagnosed him with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I said, ‘Well I guess I’ll just see it as a broken arm or something, I’ll just look after it and get on with life.’ And she said, ‘Ben, stop. It’s not like that. It’s more like cancer. If you don’t address this thing properly, you will die from it.’ And that was pretty hard.

“There was a period in my life where I was walking through the valley of the shadow of death ... [and] it took a lot of courage, and a lot of support from those around me, to be open, and opening [myself] up to people and the world around you.

“The next step was learning to be gentle with myself and gentle with those around me; and rather than trying to conquer this illness, I learnt to better manage it day to day.”

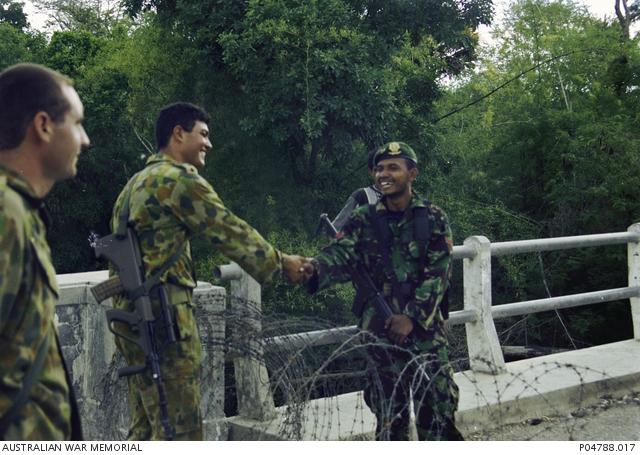

Captain Ben Farinazzo shaking hands with an Indonesian soldier, over a coil of barbed wire on a bridge over the border between East and West Timor, west of Suai

He bought a mountain bike to help with his recovery, but suffered a major setback when he was severely injured in an “unfortunate accident”.

“It was the simplest accident and I just fell off, and in the space of a millisecond I broke my neck and back in five different places,” he said. “I really hit new levels of rock bottom that I’d never experienced before, and I had to rebuild my life from that point ... How was I going to be the husband and father that I wanted to be again? How was I going to reconnect with the world in the way that I was best able to whilst managing my conditions?

“It was [my family] who did the heavy lifting. They were my connection back to the world. And that is what this is all about, recognising the families that live with this stuff day to day and help our veterans to get back on their feet.”

Ben Farinazzo addresses a group of refugees at a processing centre on their return from West Timor.

For Farinazzo, it helped to know he was not alone. “There are times when you can feel extremely alone,” he said. “And just to know that there are people around who care is more than humbling.”

As part of his recovery, he again turned to sport.

“Sport has helped me recover, both on the mental side and the physical side, to get where I am today,” he said. “Just being part of a group of people who have had extreme challenges in their lives, it’s something that really inspires me to keep going, and through that camaraderie that you get in sport, I’ve been able to take massive steps forward.”

Today, Farinazzo is a Soldier On ambassador as well as a passionate advocate for the Invictus Games and the healing power of sport.

“The Invictus Games provide a wonderful opportunity for me to connect with an extraordinary group of people who are amazingly humble, but are so focused on making a better life for themselves and the people around them that you cannot help but be inspired,” he said.

“The spirit of Invictus is about celebrating the unconquerable human soul, and to me that means being able to stand up authentically and being vulnerable and saying this is who I am: faults, smiles and all.”

The Invictus Games is on in Sydney until 27 October 2018.

Lifeline on 13 11 14

Ben Farinazzo competes in the Men's IR6 One Minute Sprint Indoor Rowing event during the Invictus Games Sydney 2018 at the Sydney Olympic Park. Photo: Defence