'Mateship meant everything'

Bill Grayden in 1940. He was just 19 when he enlisted during the Second World War. Photo: Courtesy Bill Grayden

Ninety-eight-year-old Bill Grayden knows all too well about the horrors of war.

He served as a lieutenant during the Kokoda campaign in the Second World War; his uncle was a major with the 10th Light Horse in the First World War; and his father, Leonard Ives, was left for dead after he was shot through the chest less than a week after landing on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915.

Leonard Ives was working as a mining clerk at Meekatharra in Western Australia’s remote mid-west when the First World War was declared and was one of the earliest to enlist, joining up on 21 September 1914.

"He wasn't on Gallipoli very long," Grayden said in an interview with the ABC ahead of the centenary of the Gallipoli landings.

"He was a corporal and was carrying a despatch back from the front line to his headquarters ... and he was shot through the chest by a Turkish sniper. He was left virtually for dead, but somebody saw his hand move and he was extricated, and fortunately there was a hospital ship leaving the following day, and he was evacuated on that."

Ives lost a lung, but survived the war, and went on to marry and have three children.

Like many veterans, he never talked about the war, and the only time Grayden ever heard his father mention it was when he overheard him talking to two fellow veterans at a hotel.

"I happened to be in the hotel and he met two of his friends who were in the army with him, and they were laughing about how the three of them were drawing straws on Gallipoli," he told the ABC. "They were in a trench facing the Turks and they were drawing straws to see who would put his head up next and look for a Turkish target."

Bill Grayden: "You had complete faith in the troops."

Ives’s remarkable story of survival had a profound impact on his family, and when the Second World War broke out in September 1939, his eldest son was determined to enlist.

“I was 19, and I was doing a mechanical engineering course,” Grayden said while visiting the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. “So I made an application, but they rejected it.”

Not to be deterred, Grayden changed his first name from Wilbur to William and “William Grayden” was finally accepted in 1940. His mother had already changed the children’s surnames to their stepfather’s name when she remarried. And Grayden’s younger brother David enlisted the following year at the age of 17 and went on to serve in the Middle East and New Guinea.

“You had to be 20, so I just put my age up a year in order to get in,” Grayden said with a laugh. “You took it for granted. It was just what you did … My father was in the 1/16th Battalion … so when the war broke out, I naturally joined the 2/16th.”

Grayden was appointed lance-corporal within a week of going to a naval base for training, and was soon promoted to full corporal in charge of bayonet practice. He was then chosen to attend Officer’s Training School at Bonegilla in country New South Wales, and graduated as a lieutenant before sailing for the Middle East on the Queen Mary.

“We were in the Syrian campaign against the Vichy French forces and the French Foreign Legion, but we actually had a very enjoyable time in Syria.”

The weather though presented its own challenges.

“One thing I can recall … is that about four days before Christmas, even though we were only about eight miles from the Mediterranean in an olive grove, they had three feet of snow,” he said in an interview for the 2/16th Association.

“I woke up in the morning, and made my way to the surface because every tent had collapsed during the night… The troops were in Australian summer clothing, [and] they were too cold to do anything about it. They simply propped up the canvas with their rifles and continued sleeping, so when I looked out, it was a snow scene in an olive grove – not a sign of any tent or any individual – and very shortly heads began popping out of the snow…

“But we defeated the Vichy French and the French Foreign Legion – they were established way back in about 1833, and had fought in wars all over the world; and we came from Australia and came up against them and defeated them.

“We were actually digging in on the Turkish border because they thought the Germans would come down and attempt to take the Suez Canal. And then when Japan entered the war they decided to bring us back home – and just as well.”

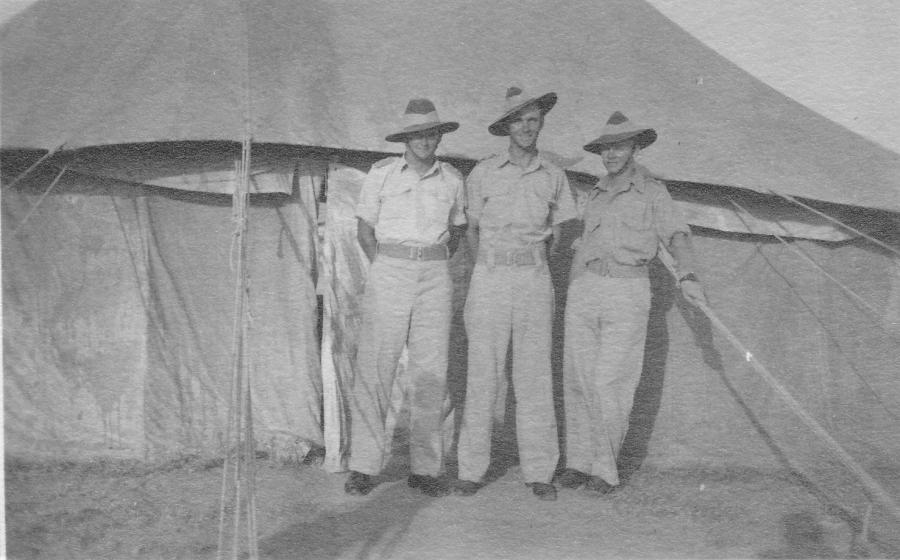

Bill Grayden leading troops of the 2/16th Battalion at Mount Garnet in Queensland.

When the Japanese attempted to capture Port Morseby overland via the little-known Kokoda Trail in the Owen Stanley Ranges in 1942, the 2/16th Battalion were sent to New Guinea with the rest of the 21st Brigade to meet the enemy.

“It was completely different,” Grayden said. “It was an arduous campaign, a constant process of slipping and sliding, and it was a very mountainous region. It rained every night, so people were sodden, and it was terribly hard, especially with the wounded, all of whom had to be carried.”

They were given “six days’ rations” and “50 rounds of ammunition only”.

“That’s why we could never think in terms of wasting a bullet,” Grayden said in an interview for the 2/16th Association. “You see what’s happening in the Middle East with people firing into the air and all that sort of thing – but we had 50 rounds and we never knew when we were ever going to have supplies renewed. We had 50 rounds and we had five tins of bully beef and five packets of what we called dog biscuits, they were very nutritional, but they were just dry, just like a dog biscuit … and that had to last us for five days.”

Grayden remembers the first time he saw the Japanese near Alola. “At brigade headquarters, I looked across [the valley] and there was a very clear area on a hill, say a thousand yards away,” he said. “It had been a native garden … and suddenly I saw about 30 people surge out of the rainforest and start frantically digging.

“We had no binoculars and we thought they were Papuans, obviously ravenously hungry trying to dig out sweet potatoes in this particular patch. We were on a slight ridge, a very exposed ridge, just standing up watching … and [very shortly, brigade headquarters] started calling out to us to get down.

“What they’d done was they’d dug in a heavy machine-gun and were firing at us, and the bullets were hitting behind brigade headquarters, and we didn’t realise this until they called out, so we got down, and very shortly brigade headquarters asked me to send out a section of my platoon, that’s about 10 men, to silence the machine-gun. But that was my first sight, and they turned out to be Japanese…

“[After that], it was all very close contact, 20 yards and all this sort of thing, and it went on for weeks. There were lots of casualties of course, especially at the beachheads, but also on the Owen Stanley campaign. The 2nd/14th was badly mauled and they just joined our battalion. Then the 27th battalion was brought up from New Guinea, and ordered to make a stand on an exposed hill. They were wiped out in one night … and it took them a month to get their wounded back to Port Moresby.”

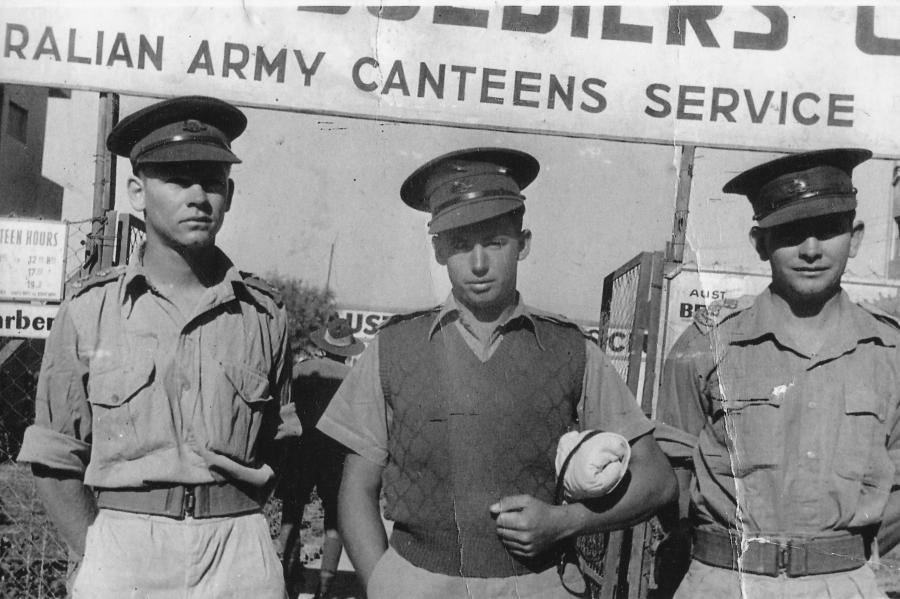

Bill Grayden, left, in the Middle East in 1941: "You had to be 20, so I just put my age up a year in order to get in." Photo: Courtesy Bill Grayden

He remembers the slightest movement could invite a burst of machine-gun fire, and that it was impossible to lie down at night because of the relentless rain; they had to sleep sitting on their steel helmets, back to back for support, and with one ground sheet between two men. Marching in single-file in the pitch black of night, they would tuck a piece of phosphorescent fungus into the back of their belts to help the person behind follow them.

One morning, Grayden awoke in bright sunlight to find the whole platoon sound asleep. Exhausted from days of fighting and the gruelling trek over the ranges, the sentries had fallen into a deep sleep and failed to wake the next shift up. Looking over a log that was lying across the track, Grayden was even more horrified to discover the brigadier, Arnold Potts, also sound asleep.

“During the night they must have all fallen asleep,” he said. “It must have been about seven o’clock or something and I looked around and the whole platoon is sound asleep. There was a log across the road two feet above and I looked over the log and here’s Brigadier Potts – the brigadier, in charge of three battalions – lying with this ground sheet around him, nothing else, sound asleep … apparently confident in our diligence. And we were the only troops between the battalion and the Japanese.

“Now being a lieutenant, I thought it was advisable to wake the platoon up before I woke the brigadier. He went back to brigade headquarters ... [and] about less than half an hour later, two Japanese came, not walking up the track, but trotting, and very shortly after, we got the order to withdraw to a higher position.”

Bill Grayden, pictured far right, in the Middle East in 1941. Photo: Courtesy Bill Grayden

More than seven decades later, the memories of that time remain vivid. “Yes, they are – completely,” Grayden said. “They are very fresh indeed, right down to details, and even the expression on people’s faces.”

He still remembers the fighting at Brigade Hill as if it was yesterday.

“The Japanese had got behind us, and between our three battalions and brigade headquarters, and we had to clear them,” he said. “They were on a saddle, and it was a bayonet charge against troops that were ensconced in slit trenches and foxholes. We immediately lost about 65 or more than that in casualties, in just five minutes.

“We only had to go 100 yards, and we had at least 65 casualties with, say, 40 killed. I was the only officer to get through because they were all either dead when I reached them, or if they were up in the trees – which they were – they wouldn’t fire down if you were right underneath in case you would look up and shoot them. They waited until you got a few yards further on, because if you were looking at the ground you weren’t looking up at them.

“We came to a terribly defined track and it was obvious one or two companies had walked along the track during the night. They had walked across in single file exactly as we would have done … but it was such a well-worn track, and they wore special shoes, [so] you could tell immediately it was the Japanese because they had a special place in the shoe for the big toe.

“So we followed the track right to the crest of the hill. We spread out two yards apart, only the six of us, and we were crawling up, not knowing, and we get to the crest of the hill. Tommy Foy was my platoon sergeant … I was looking at him, he was two yards away, and we were in undergrowth say two feet high … and he crawled across this open space … and he lifted his head and he got a bullet from say six yards straight through his throat and the full length of his body, killed instantly.

“Now, we couldn’t see the Japanese and they couldn’t see us, and we waited there silently because there was nothing we could do… We were reconnaissance… In the night they had dug foxholes and camouflage. We slither back and report to the headquarters where the Japanese were ensconced and the number that were there.”

Bill Grayden visiting the Memorial in 2017 for commemorations marking the 75th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign.

The battle proved to be one of numerous close calls for Grayden.

“Oh, constantly,” he said. “It was just a constant process. We were in contact with them for weeks, and because they outnumbered us, and because they had superior weapons, [we] had to adopt different tactics all together. You didn’t just make a stand … you fought a strategic withdrawal [where] we’d go back on to a ridge, they would attempt to attack, and we’d inflict casualties on them…

“They would attempt to surround you once they had fixed you down, so when our scouts indicated that they were coming around, we’d withdraw to the next ridge again. And that went on from every ridge, all the way back, so we were in constant, daily contact, every day, for weeks.

“Then by the time we got back, we made a stand on Ioribaiwa Ridge, about 60 miles out of Port Moresby, and they shelled us for a week. They wouldn’t attack us, but every day, on an exposed ridge, the shells would burst in the trees above.

“It wasn’t worthwhile even digging [a foxhole], so my platoon sergeant and myself, we didn’t bother. We were just lying there for a week, shelled every day, machine-gunned, but they wouldn’t attack, and then they got the order from their emperor to withdraw back to their beachhead. And that was good. That was very good from our point of view.”

He pauses quietly when asked if he was frightened. “Oh, well,” he said simply. “You were up against them all the time, and for so long too… The day before we were relieved, they were shelling us, and about eight yards away was a slit trench with two people in it. One got hit right across the head, kicking in the trench, so the [other] bloke got out [and] got behind a big tree on the lip of a hill.

“It was a very steep drop … and another one had been coming up from further down the ridge. He’d been hit in the back with a bit of shrapnel, and it had taken his shirt off. There was a cut right across his back, and he got behind the tree, so that meant two of them were behind the tree.

“I was just lying down 10 yards away, and there was a lull in the shelling [so] I got out [and] I went down to put a shell dressing on him. The one with the big cut got hit again with another bit of shrapnel … so I got out to put a shell dressing on the second cut [or] wound that he’d got, and that then made three of us behind the tree.

“I put my thumb up against the tree to steady myself and I saw the flash of their guns 500 yards away. The shell hit the root of the tree two feet away – 15-inch shell – blew these two people to pieces, and blew me down towards the enemy.

“It was reported that I’d had my head blown off … [but] I must have been unconscious. And when I recovered I clambered back up to the top, but I’d had both ears perforated. I didn’t smoke, but somebody offered me a smoke and I took it, and I could blow smoke 15 inches out of both ears.”

Bill Grayden laying a wreath at the Memorial with fellow veteran Les Cook.

For Grayden, it was a relief when the campaign was finally over. “I don’t know how one would describe it,” he said. “It was fantastic.”

But it wasn’t the end of Grayden’s war. After a brief respite, the 2/16th Battalion was sent to help drive the Japanese from their bases at Buna and Gona on the northern coast of New Guinea and took part in the Ramu–Markham Valley campaign and the beach landings at Balikpapan in Borneo.

When the war finally ended, Grayden was on a five-day patrol behind enemy lines in pursuit of the Japanese and couldn’t believe it was over.

“We were halfway across Borneo,” he said. “We had been there at the landing at Balikpapan and we had to pursue the Japanese … We were never sure of the numbers, but there were supposed to be 40,000 in the area…

“Again, I don’t know how to describe it, but we were delighted. It was so unexpected. We didn’t anticipate the ending at all, and we were actually in really close contact, and there were so many of them.”

He’d been promoted to captain after the Ramu–Markham Valley campaign, and was involved in the surrender of Japanese forces on Celebes where he helped supervise the repatriation of Japanese troops to Japan.

He finally returned to Australia in 1946 and was elected to the Western Australian State Parliament as the member for Middle Swan in 1947. He was the youngest member of the Parliament at that time, and was elected to represent the Federal seat of Swan in the House of Representatives in 1949. In 1956, he returned to the Western Australian Parliament where he served until his retirement in 1993, earning the title of the longest-serving parliamentarian in Western Australia.

But Grayden never forgot his father’s sacrifice during the First World War, and at the age of 94, he set foot on the beach on Gallipoli exactly 100 years after his father did the same. He was one of several hundred Australians who attended the Anzac Day Dawn Service in 2015 as a direct descendant of a Gallipoli veteran. And that same year, Grayden published a book, Kokoda Lieutenant – the Triumph of the 21st Brigade: recollections of an AIF platoon commander 1942, about his own experiences of war.

Today, the father of 10 is still the president of the 2nd/16th Association and remains passionate about remembering those who fought and died during the war. He attends commemorative ceremonies whenever he can, and laid a wreath in memory of his mates at a Last Post Ceremony commemorating the 75th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign at the Australian War Memorial. To him, it was a particularly special moment.

“Mateship meant everything,” he said quietly. “[The commemorations are] an opportunity to pay tribute to those who lost their lives, and those who were wounded … I was a lieutenant with 30 men under me, and later a captain … [and] you had complete faith in the troops, but mateship, that was everything.”