'There was a bond of friendship and mateship money couldn’t buy'

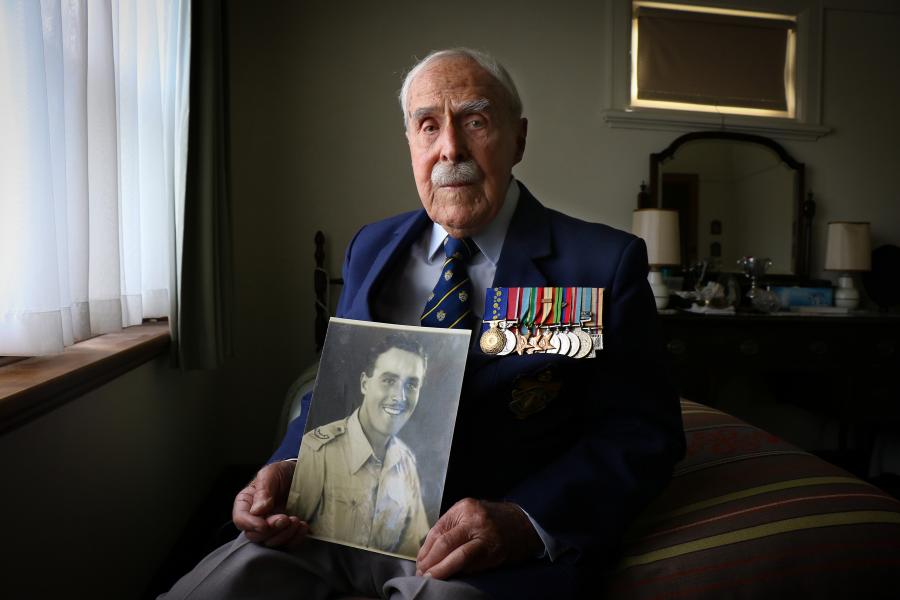

Rat of Tobruk Bob Semple at his home in Essendon. "You’ve got your complete trust and faith – implicit faith – in your mates." Photo: Leigh Henningham

Bob Semple turns 98 next month, but he remembers the siege of Tobruk as if it was yesterday.

“I well remember it,” he said quietly. “It was only going to be for a couple of months or so, but it turned out to be 242 days, all told.”

For eight long months in 1941, 14,000 Australian and other Allied troops held the strategic Libyan port of Tobruk in what was to be one of the longest sieges in British military history. They were surrounded by a German and Italian force commanded by General Erwin Rommel, the “Desert Fox”, and they withstood tank attacks, artillery barrages and daily bombings in one of the most bitterly fought campaigns of the Middle East and Mediterranean fronts.

“We were no better than any other soldier, but … we were lucky,” Semple said. “I suppose you go wherever you’re put, and you wonder why, but you accept the circumstances.

“There were no trees on the joint at all, and [when we arrived] we thought, God. There were a few picks there, and we were told, you’d better get to work and see if you can dig a hole for yourself because you’ll get some guns in the morning. When the morning came, there was this great heap of old Italian guns … but the biggest problem was they were all in the metric system, and we’d been trained in the imperial system, so you had to convert it all. They’re the tools of the trade, and you just had to go with it, and you had to depend on your mates.”

They lived in dug-outs, caves and crevices for months on end, enduring searing heat during the day and bitter cold at night, as well as hellish dust storms.

“It was a bit tough,” he said, simply. “You had one water bottle a day for all purposes, and it would be 48 degrees, so we were euchred physically as much as anything else, and it’s very wearing on the mental factor.”

Bob Semple, far right, in the desert during the war. Photo: Courtesy Bob Semple

He will never forget watching the Stuka dive bombers as they flew in to attack.

“The biggest raid we had on Tobruk, I suppose, would have been about 100 planes,” he said. “They even bombed the hospital, and everything else. It was pretty chaotic. Sometimes you’d get three raids a day [and] 20 or 30 planes would come up, and they’d shoot you up, and you couldn’t move. You couldn’t up sticks and go somewhere else. You just had to take it. And the fleas and flies – the fleas were even worse than the flies, I think.

“We were short of any sort of food, and it was all hard rations, and that’s pretty hard to take, but they’re facts of life, and you weren’t the only one that was dealing with it. You had to think of your mates.”

For Semple, mateship meant everything during the war. “It’s hard to explain, but there was a bond of friendship and mateship money couldn’t buy,” he said. “You’ve got your complete trust and faith – implicit faith – in your mates.”

Even as the siege dragged on, they never thought of giving up.

“No, never,” Semple said. “We didn’t give in, and we didn’t want to give up. When [General Leslie] Morshead, our commander, took a left turn at Tobruk, he said, ‘We’ll hold this place. There will be no surrender.’ I well remember it. He said, ‘There’s only one way out of this – we’ll have to fight our way out.’ And the blokes just took it on. He was a great leader [and] we had great faith in him. They called him ‘Ming the Merciless’, and we were known as the 20,000 thieves.

“There was no alternative. You couldn’t go anywhere. You couldn’t swim away. It was a long way to go if you did, so you just had to get on with it … You had to try and win the game because if you weren’t there to try and win the game, you were wasting your time. You had to believe in the fact that we’ll win this.

“There was this Lord Haw Haw, as he became known, and he said we were living in the desert in holes in the ground like rats … so then we became known as the Rats of Tobruk and we thought, that’s not a bad name.”

Semple turned 21 during the siege, and will never forget how he felt, when they were finally relieved. “You didn’t get excited about it, but you knew what your mate was thinking: ‘What a Godsend this is.’”

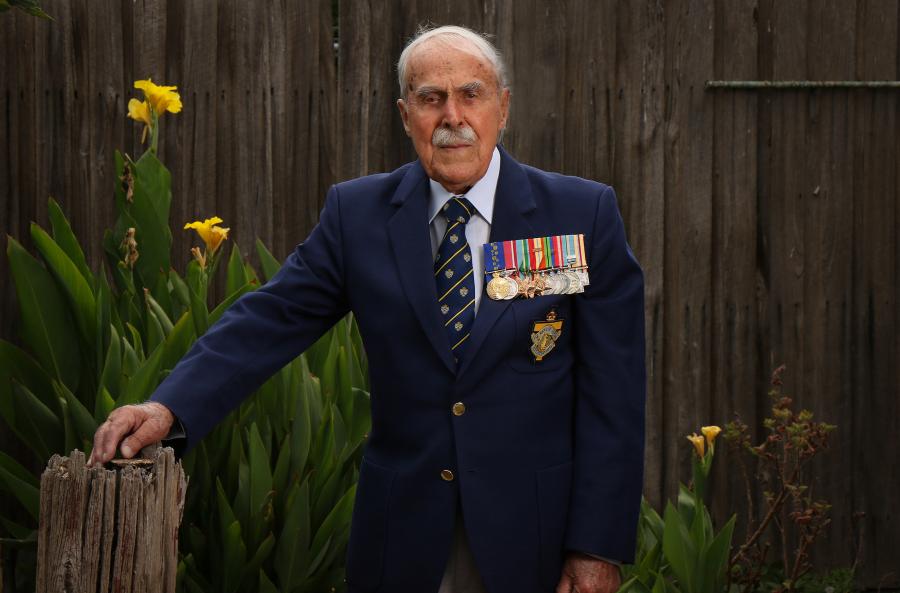

Bob Semple: "You just had to go with it, and you had to depend on your mates." Photo: Leigh Henningham

But the siege of Tobruk was just the beginning of Semple’s war. He was sent from the blistering heat of the desert into the the snow of Lebanon before being sent back to the desert and the tiny Egyptian railway stop at El Alamein in July 1942.

“That became a different war again,” he said. “It was shock and shell, and it was a big, big show … We lost nearly a battalion in one morning. They got into a mine field and the Germans had it covered… What they didn’t kill, they took prisoners of war … Some battalions had fronted up there, going in with 150 or 200, and there was only about 30 or 40 left…

”When [an armour-piercing] shell hits tanks, it’s horrendous. There were blokes jumping out of them on fire, and the shells are whizzing around inside the tank, and you just had to put the tin hat on, I suppose.”

He will never forget the opening barrage of the second battle of El Alamein on 23 October 1942.

“It was murderous,” he said. “There was something like 800 or 1,000 guns opened up at the one time. It looked just like a whole lot of glow worms had turned up, and the sky was alight…

“Two searchlight beams went up into the air and they locked, and that was the signal. We all had synchronised watches and all that sort of thing…

“The infantry then started to move… and the engineers had to go in. There was that much ironmongery about, with shrapnel and all the rest of it, the blokes were down on their hands and knees in a lot of cases, digging mines out [of the minefield] and then passing them on to one side, delousing them, and then trying to open up gaps in the barbed wire…

“On the 25-pounders, we would have averaged 600 rounds of ammunition between that time and dawn the next morning, and that’s one gun, and there were nearly a 1,000 guns.

“It was unbelievable, the noise. It was just like a series of trains going past … Half of the German soldiers were dopey, of course, after the shelling they’d had in a lot of places, and they were almost round the bend, but we got back a lot of shelling from them too.

“With the vehicles and everything else, the dirt or the sand … was like talcum powder. It was churned up to such an extent that when the wind came up it was like a big fog.

“They’re just the hazards of the business and it had to be done [but] the sandstorms were hard to take. When the sandstorms came up … it was just like pulling [a] blind down from the sky to the ground as far as you can see.”

Semple considers himself lucky to have survived. “Even as the shells are coming in, you don’t knock off, you just keep going,” he said. “You see blokes who have been hit in a tin hat [who] are not hurt, and other blokes [who] are in bits and pieces. Why does that happen? Why does a shell come into a gun pit and the blast take part of your crew and not others? I don’t know. You just reflect back, and it’s a game of fate, really.”

He admits there were times he thought he wouldn’t make it home, but he tried to put those thoughts to the back of his mind. “I tried to be positive and say, look, I’m going to make this,” he said. “I’ve always been taught to wear it, and don’t be frightened to go the extra mile ... [but] when you haven’t got replacements, or you haven’t got the equipment, you’ve got to be honest and accept the fact you are fighting an uphill battle...

“There are moments when you see horrible things and you think to yourself, why? But you try to discipline yourself and overcome that.”

Bob Semple in New Guinea. "It was different warfare altogether." Photo: Courtesy Bob Semple

In 1943, he was one of 34,000 Australian troops who were brought home from the Middle East and were sent to fight the Japanese in New Guinea.

“It was different warfare altogether, and there were no beg your pardons with those fellows,” he said. “It was a case of come home, straight out of the desert, get a change of gear, and then you were in action on the islands … We had to change uniforms into the jungle green type of stuff – and the equipment, we just had to modify it as best we could because the heavy vehicles were not much use in the jungle area… There was nowhere near the amount of ironmongery thrown around – as far as the volume of fire was concerned for obvious reasons but it was more testing on the nerves and your mind. The unseen is a bit hard to cope with … [and] the conditions were pretty frightful.”

His regiment was involved in the sea borne operations at Lae and Finschhafen, where they battled malaria as well as the enemy. “We were swallowing those yellow pills, and all sorts of things, and looked like a canary after a while,” he said with a laugh. “But malaria took a toll on a lot of the blokes. Of all the casualties in my regiment, malaria would have probably accounted for about 60 per cent … Then Japanese were in the bush, and they gave us a bit of a rough time.”

When he returned to Melbourne on leave he married his sweetheart, Isabel Buchanan, at his local church in Essendon. He carried her picture with him throughout the war, as well as the New Testament he’d been given as a boy at Sunday school. They were married for 55 years when she passed away in 1999.

“She was the only girlfriend I ever really had,” he said. “We were thinking of getting married [before I went away to war] and I said, ‘No, if I get knocked off you’d be better on your own.’ … I was away then in the Middle East for about two and half years and spent three Christmases in Palestine, and then we got married when I came home from New Guinea. That was in 1944. I had three weeks’ leave, and then went away again to see out the rest of the war.”

But the wedding nearly didn’t happen. “The best man was one of my mates in my troop … and I thought we’d turned up at the wrong church on the wrong day, to be quite honest.”

They were sitting on the steps of the church, but the doors were closed. It turned out they’d “been miscued on the time” and the wedding went ahead.

“We went to Daylesford for what was to be the honeymoon and I nearly died up there,” he said. “Malaria took over, and I got hit. I felt a bit seedy the day of the wedding, and I began to heave up blood and everything else, and so we had to come home from there, and I had to go straight to hospital.”

He was at Beaufort, 50 miles up the Parker River in British North Borneo when the Japanese surrendered on 15 August 1945. He was discharged at Royal Park in Melbourne on 13 November. After almost six years of war, Semple’s war was finally over. He’d served for a total of 1,975 days since he first joined up on 18 June 1940.

After the war, he admits he “felt at sixes and sevens” for a while, as did a lot of his mates.

“There were a lot of blokes who could never ever relate to their families again,” he said. “They had to get used to the regularity of working and trying to find something to do that they could live with. They knew where all the pubs were … And some of the blokes – even when you were able to sit down and say, ‘Well listen, how’s Mary going with the kids and all that? How are you tracking?’ – they would just go into a fog.”

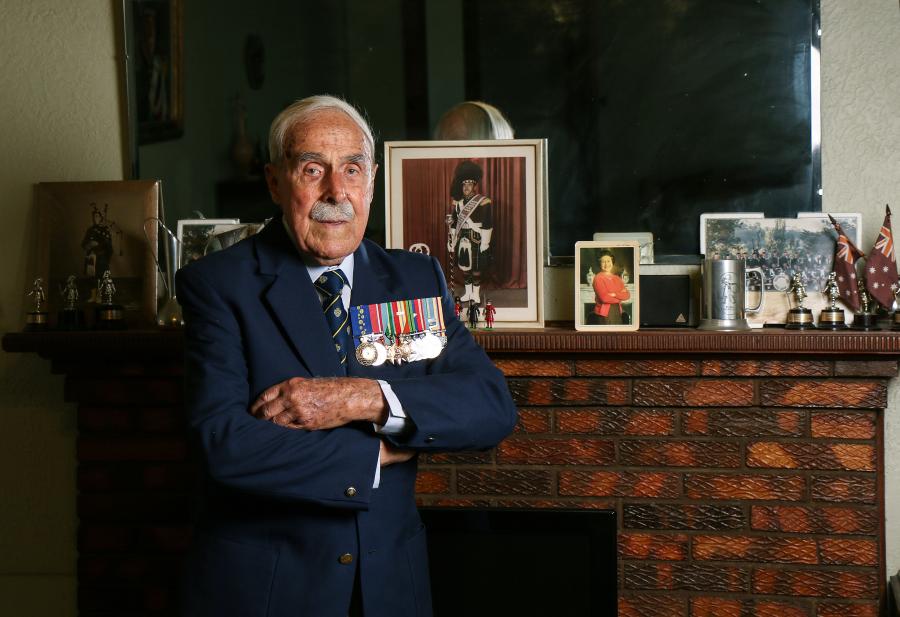

Bob Semple in his home at Essendon. Photo: Leigh Henningham

Walking in Moonee Ponds one night with his wife, he was moved to see the Hawthorn City Pipe band playing in Queen’s Park, and promptly joined them. “That was in October 1945, and I’ve been with the band ever since,” he said.

Semple is now Drum Major of the Hawthorn City Pipe Band and chieftain of Pipe Bands Australia. He has performed in Red Square in Moscow and at the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo in Scotland four times. He will never forget being in Edinburgh, when he was asked to report to the commandant’s office to meet a major in the Royal Highland Fusiliers. Semple had been given luxury accommodation and thought he was in the wrong room, but the officials had assured him it was correct. “He said, ‘You’re a Rat. We’re brother soldiers.’ Well, what do you say? And that’s the only time it gets me stirred up a little bit, when you say, ‘Well, what have I done to deserve this?’

“And I’m not ashamed to admit that when I went across that drawbridge, all these things came back and hit me, and I thought how can I handle this? It brings tears to your eyes.”

Today, he is president of the Victorian Rats of Tobruk Association, which established the Rats of Tobruk Pipe Band as a living memorial to those who fought and died during the siege. He and his fellow Rats talk to school children about the war, and the stories and poems they write to him afterwards are some of his most treasured possessions. He still rises at 5.30 each morning, makes his bed in a military fashion, and goes for a walk whenever he can.

He has returned three times to the desert, where he has played the lament at the war cemetery at El Alamein, and visited the graves of his mates who are buried side-by-side in the desert sand. Looking back, he still wonders how he managed to survive it all.

“Oh, absolutely,” he said. “I haven’t got any particular qualities that I know of, other than the fact that I was just not meant to go at the time I suppose, and that’s all I put it down to, and accept the fact … You’ve got to be honest with yourself and say yes, it does affect you at times. But the big thing is to accept reality and pay your respects wherever you can.

“I’ve been at reunions where you would just look at one another, and say nothing, and the tears would just roll down the faces … [And] to shed a tear is not a disgrace in my book.”

Rat of Tobruk, Bob Semple, OAM BEM, will be speaking at the Anzac Day National Ceremony at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

Bob Semple playing the lament at El Alamein. Photo: Courtesy Bob Semple