'They are lifetime experiences I don’t think anyone would forget'

Brian Cooper was 19 years old when he had to call down artillery onto his own position during the battle of Samichon River in July 1953.

“I reckon my luck’s been used up,” he said.

“The fire was right on top of us and the noise was horrendous … We were in weapon pits, so we ran a certain amount of risk, but not as much as the Chinese.

“We knew it was coming and we could get down, whereas the Chinese were out in the open, so they were just going to cop it.

“I had words with the great Godfather up above, and I said to him, ‘Well, if it’s going to be me, I’d like it to be quick.’

“I didn’t want to be wounded and lying around, or taken prisoner or something like that, and I said, ‘If you can, go easy on my blokes.’

“And that’s the extent of my religion.”

Brian Cooper on a field telephone at Hill 159 in May 1953.

A sergeant in command of one of four sections of 2RAR’s medium machine-gun platoon, Brian had been stationed with US Marines on Hill 111 to provide fire support and guard the western approaches to the Australian lines on “the Hook”, near the Imjin River in North Korea, when they suffered repeated artillery barrages and waves of enemy infantry attacks on the 24th and 25th of July.

“It was terrifying, I can tell you that,” he said.

“I’d called down our artillery twice during that night, and I called them a third time, but they wouldn’t come.

“As far as I was concerned, and I think the rest of my blokes were concerned, we were done for – we were history – so it wasn’t too hard to make that decision.

“You just got down in the communications trench, and hoped to God that a shell didn’t drop in next to you.”

Brian was awarded the Military Medal for his actions on Hill 111 and celebrated his 20th birthday a few weeks later.

Sergeant Brian Cooper, right, holding a bottle of beer, part of a gift parcel from the RSL, with Corporal Ron Walker, in August 1953. Both men had been involved in the defence of Hill 111.

A former painter from Western Australia, Brian was born in East Perth in August 1933, and left school at 14.

When he enlisted in the Australian Army in 1951, it became like a second family to him.

“I joined the army when I turned 18, and I was there for the next 18 years,” he said.

“I’d done a year in the Citizens Force before I joined the Regulars and was in 10 Transport Company. They taught you how to drive, and how to maintain vehicles, and all that sort of thing, and I just loved it; I couldn’t get enough of it, so I thought, ‘I’ll join the Regulars.’ When I went to sign up, I told them about my previous service, and said I wanted to join the Royal Australian Army Service Corps and be with transport. ‘Oh, yes, no trouble at all,’ said the allocation officer. But then, eventually, after recruit training, I was posted to 2nd Battalion, and there was a sign when we arrived, which said, ‘You are now the proud member of an infantry battalion, despite the promises of your allocation officer,’ because all they wanted in those days was infantry to make up the numbers for Korea.”

Pusan, Korea, 1953. The ship New Australia carrying troops of 2RAR as it is about to pull into the harbour.

Brian sailed with the battalion on QSTEV New Australia and arrived in Korea in March 1953.

“The ship pulled in to Pusan, [and we thought], ‘Oh, God, help us,’” he said.

“It was a war zone, and it was obvious right from the beginning. There were millions of people everywhere, and everything was filthy; you couldn’t get a decent building or anything; they’d all been blown apart. It was one thing to have seen war movies and war footage, and London, and all that; you thought, ‘Oh God, that’s awful, but that was over there, it won’t be like that for us.’

“Like hell!

“Korea had suffered years of Japanese occupation as well and that had taken a terrible toll … so they were very suspicious of any conquering armies or that sort of thing.”

Brian was put in command of a section at “Vickers Village”, a platoon position of four guns, and was positioned in the machine-gun bunker on Hill 111 during the battle of Samichon River – the Hook on 24–26 July 1953.

“The first half of the war was a mobile phase, and everybody was on the move, but the second phase was all defensive, so we were in firing positions, bunkers, dugouts, weapon pits, and all that sort of thing,” he said.

“Triple one was next to the Hook, and the Hook was arguably the feature that cost more lives –UN and Chinese – than any other feature in Korea.

“It was very prominent, and there was a ridge on it that looked like a hook on a fishing line that jutted into the Chinese area. They didn’t like that at all, so they liked to keep us off it, but we liked it of course, because when you put people out there they could see what was going on in the Chinese area.”

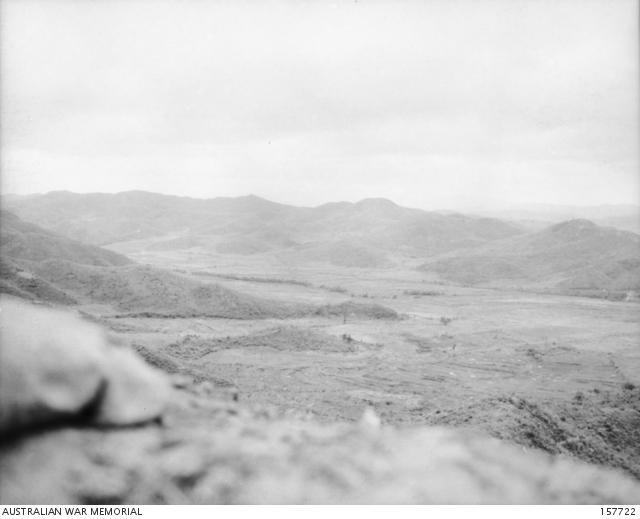

Majon'ni, Korea, July 1953. Aerial view of The Hook defences.

He remembers a heavy attack on Hill 111 on the 19th and 20th of July.

“During the night, about 2,500 rounds of artillery and mortar came in, varying from 76 mm to about 120 mm, and we thought, ‘Well, this is it.’

“It was only about 500 metres to where the Chinese were and they were coming across open ground to our defensive positions …

“I had a two-inch mortar, and illuminating rounds, so I kept popping those up, and the marines appreciated that … but we had artillery support as well, so they didn’t have a lot of chance.

“It petered out about one or two o’clock in the morning, and there were quite a few bodies in front of our positions, so we thought, ‘That’s it, that’s our battle.’

“But it was only a rehearsal. It was a rehearsal for the 24th, 25th and 26th …

“Over the years, the Chinese had tried to break through and get behind the UN line by attacking the Hook, and the forces that were on there, but they suffered badly because it was a very difficult feature to take.

“The US Marines had been on it at one stage, were thrown off it, and then took it back again; the Black Watch, or the Royal Scots Regiment, had fought a big battle for it; and a battalion from the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment had fought for it as well, and they were the ones we actually took over from.

“The defensive positions were like a moonscape because there had been that much shelling from both sides, and it had all been blown apart … They fought over it all the time, so they expected everything to be happening up on the Hook, but it wasn’t; they picked on us next door on Hill 111, and it all happened again on the 24th and the 25th.”

Majon'ni, Korea, July 1953. Forward slopes of a portion of The Hook defences.

Leaving enough men to man the guns, Brian organised the remainder into a separate defensive position, and engaged the enemy with such a volume of grenades and small arms fire that they were unable to penetrate the position, despite overwhelming superiority of numbers.

“That night there was a tremendous amount of artillery and mortar coming in from them,” he said.

“They knew where everything was in our position, and it was said afterwards that it was because we had Korean porters and some of them were actually Chinese stooges. They used to tell them everything; where it was, where it was facing, and so on, so they knew where everything was.

“I had two blokes wounded straight away. One fellow got the blast from what we think was a 76 mm shell; it was head high, and it burst his ear drums, and his face got sandblasted. He didn’t get shrapnel, but he was stone deaf at that stage, and the other fellow had been sent up to look at our position and everything in it. He was a corporal for the next section who was going to relieve us, and he got hit in the arm with a bit of shrapnel. It opened the veins in his arm and we couldn’t close it with shell dressing; it just wouldn’t stop, so he had to hold one hand over it and squeeze it to keep the blood from going, otherwise he was dead…

“I arranged by radio to get something to get them out. You couldn’t bring a jeep ambulance up there, and you couldn’t walk them out because they would never survive, so they sent up a tank. It’d had the turret removed, and was used to carry ammunition, or water, or food, or whatever, up the line, and had two steel doors on it, so they took the wounded out in that ... The few shells hitting around it didn’t bother the tank too much, but a direct hit of course wouldn’t have made them laugh.

“The third casualty didn’t occur until the next morning. One of my corporals said, ‘We’re not sure about this bunker next to us, we think there might be a Chinaman in there.’ I said, ‘Yeah, be careful,’ and so they went up there to have a look, and they were greeted with a grenade.

“He got it in the posterior, but it was a fleshy wound, so he said, ‘I’m right, I’m right,’ because I was short of men, and I couldn’t really spare another; I’d have been down to six of us to cover the position, and there were already about 300 dead Chinamen in front of the position.”

Majon'ni, Korea, July 1953. View along the valley of No Man's Land in front of The Hook defences.

Several of the Marines’ forward trenches had been taken during the attack and the positions on Hill 111 were only saved when Brian called down artillery twice onto his own position.

“It was frightening; you can say that,” he said.

“You are a 19-year-old sergeant, and you’re responsible for all these other fellows; you could give them an order to do something, and they could get killed…

“In my section, I had two corporals – they were the number ones on the machine-guns – and both those blokes were about six months younger than me. The oldest bloke was an Aboriginal fella who was in his 40s, but otherwise they were all whipper snippers like me … so it’s not just the fact that you are terrified in a fighting position worried about your own health, but you’ve got all these fellows, and you are responsible for them.

“You can’t just sit down and say, ‘I’ll cry this out,’ because they are waiting to get orders, and asking, ‘What do you want us to do?’

“So I think, for me, one of the worst things, was having to think all the time about what you should be doing.

“You’re giving blokes orders, and you had to be aware of what was going on, so most of the time I had the bloody radio glued to my ear.

“The platoon was asking all the time, ‘What’s happening? What’s happening?’ and the corporal would stick his head in, and he’d say, ‘They’re throwing grenades at us, what do you want us to do?’ and I’d say, ‘Throw the bastards back ...’

“I also had with me a 3.5 inch-rocket launcher and some ammunition. They’re an anti-tank weapon, and the next morning one of the marine sergeants came to me, and said, ‘Can I borrow your rocket launcher?’ This is an American weapon mind you, and we’d never had any instruction on how to use the thing, but he said, ‘I’m going to knock the Chinese out of these bunkers that they’ve occupied,’ and that’s what happened…

“We were very glad when it was over, but we weren’t sure of course that it was over on the morning of the 25th. Things happened very quickly from then on, and they did make another attempt on the 25th, but it had no chance of winning…

“On the night of the 25th, one of the gun bunkers that had two blokes manning a machine-gun in it was hit by a shell and it caved in. The blokes were buried in it, and their mates had to get them out … I met one of those blokes later in life; he’d been evacuated, and he knew he’d been buried, but he didn’t know what had happened to him, so I told him what had happened and that relieved him quite a bit … it was a just direct hit on the bunker and they were buried alive.”

At 3 am on 26 July, the Chinese senior command called off their offensive. It has been their last-ditch attempt to wrest strategically important territory from UN forces. The following morning, the formal armistice was signed at Panmunjom, taking effect at 10 pm that night. Over the following days, UN and Chinese forces each withdrew two kilometres, the vacated ground becoming what continues to this day to be known as the Demilitarized Zone or DMZ.

A group of soldiers of the 2nd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (2RAR), boarding the ship New Australia for their trip home to Australia.

Brian returned to Australia in April 1954, where he met and married the love of his life, Margaret, who had written to him during the war.

“We became pen friends when I was in Korea,” he said. “Somebody wrote to the Goulburn Evening Post, and said, ‘I’m Snowy Barnes, and I’m a lonely soldier in Korea, and I’d like young ladies from Australia to write to me, and so on.’

“He put John Perrin’s name in there, and of course all this mail arrived for John Perrin who was ready to kill somebody because he’d got engaged just before we left. I said to these blokes, ‘Righto, you’ve done this, you’ve got to answer all these now,’ and I farmed them out to the blokes, and dictated a letter, a very short one: ‘Dear Mary, or whoever, thank you so much for writing a letter, I have 24 other letters to answer, and I simply can’t take anymore, thanks very much.’

“Anyway, one little bloke said, ‘What about you, serge?’ And I said, ‘Yes, I’ll take a couple, so I put a couple of letters in my pocket, and one of them was from my wife…

“She was out on the farm, and one of her brothers, who was an ex-commando from the Second World War, thought she was moping around. In actual fact, she liked her own company, but he said, ‘Why don’t you write to this poor bugger in Korea?’

“He kept at it, so she wrote a letter, never intending to post it, but he got it, and posted it … and so that’s how it all happened.”

The pair married in November 1954. They have been married for more than 60 years and have two children, five grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

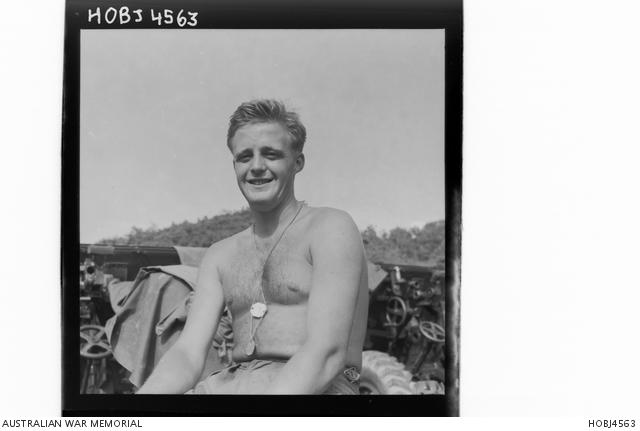

Informal portrait of Sergeant Brian Cooper in August 1953.

After the war, Brian went on to serve with the 17th National Service Battalion and the School of Infantry.

He remained in the army until 1968, reaching the rank of warrant officer class I, and was made a life member of the 1st Marine Division Association.

“They are lifetime experiences I don’t think anyone would forget,” he said.

“You were there, and you were amongst it, and that was it … That’s what you were sent there for …

“I think I was very hard to live with over the first few years – my wife will be nodding her head now, and I’m sure I was …

“I don’t have any emotions – I think that was knocked out of me – but you were very delighted to be out of that lot.

“I was quite pleased to get [the Military Medal], but you think, what about the other blokes?

“I got my prize from my action in Korea in that I’m still here talking to you.

“That’s the best prize I could get.”

Brian Cooper’s flak jacket and medals are on display in the Korean War galleries at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.