The search for peace

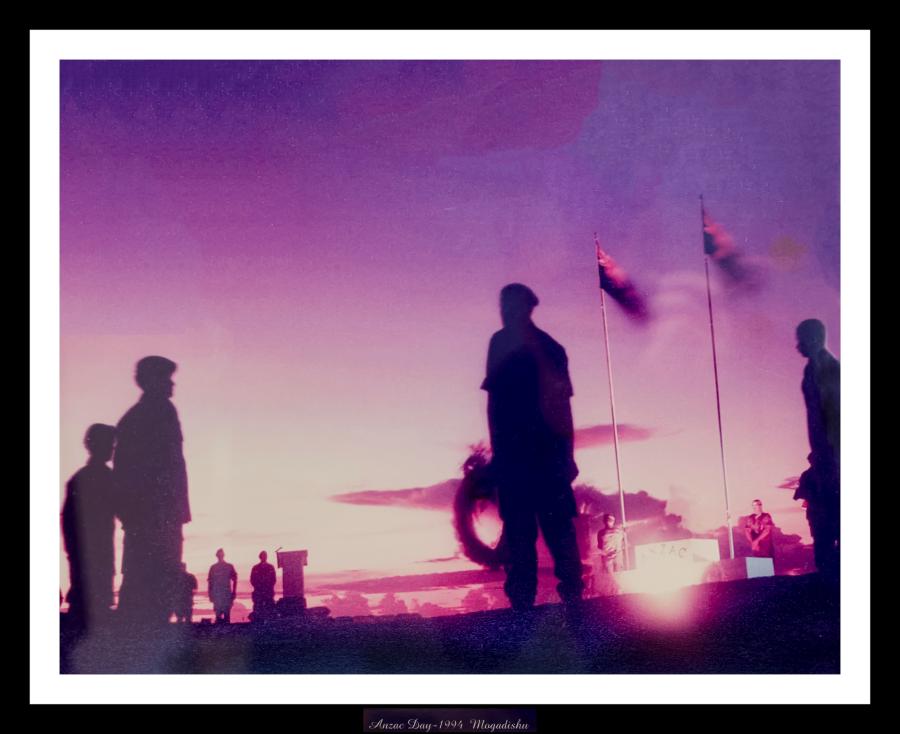

The walls of Brian Dawson’s office are lined with photographs, but one in particular stands out. It’s Anzac Day 1994 and soldiers are silhouetted against the sunrise at the dawn service. It could be anywhere in Australia, but it’s not. It’s Mogadishu, the capital of in Somalia, and it’s one of the most dangerous places on earth.

“I did wonder, if I was killed there, what was the point? And I guess I rationalised it by saying that I was a professional soldier, and that my country asked me to go, and that’s why I was there,” Dawson said.

“It was pretty chaotic at the time and it was a very difficult environment to operate in. To drive from the base, around the university to the airfield and port was quite a dangerous activity and one you only did if you absolutely had to do it.”

Dawson was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Australian Regular Army when he was deployed to Somalia from October 1993 to May 1994 as part of the United Nations Peacekeeping Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM II). Drought, famine and civil war had reduced Somalia to a state of anarchy in the early 1990s when the United Nations stepped in with UNOSOM I and the United States subsequently led an operation called UNITAF.

Dawson’s second child was six weeks old when he was deployed to Somalia just after what became known as the Black Hawk Down incident. The incident is the subject of a book and film chronicling the events of the 1993 raid by the US military against faction leader Mohamed Farrah Aidid and the ensuing firefight known as the battle of Mogadishu.

“The force was basically in shock,” Dawson said. “There were about 73 wounded, 19 killed, and a number of helicopters had crashed and not been able to be recovered.

“In my opinion, the United Nations probably had an impossible task there, to separate and control what was a pretty fractured body with some pretty ruthless people on all sides, who were squabbling over the bones of Somalia.”

It was a dangerous and confronting situation for the peacekeepers.

“With the benefit of hindsight, there was a fair bit of naivety about how violent these conflicts could get, very quickly, and it just spiralled out of control,” Dawson said.

“We’d been trained by men who had been through the Vietnam War, so I never felt that we didn’t have sufficient tactical skill to do what was required of the mission, or that we lacked the training or military education – but it wasn’t the classic guerilla warfare that we’d been trained to expect.

“No one really had a good template for how this was supposed to play out, but we were probably stopping things going further downhill in Somalia just by our sheer presence. I’m sure there were a lot of bad things happening there, and any military force is a blunt instrument; but in the time we were there, we were probably doing more good than harm.”

Australia has been involved in peacekeeping operations since September 1947, when four Australian military observers were deployed by the United Nations Consular Commission to observe a ceasefire in the Dutch East Indies. Since then, Australia has provided military, police, and civilian personnel to more than 60 United Nations and other multilateral peace and security operations. But it has not been without sacrifice: 16 Australian peacekeepers have been killed on duty. Their service was commemorated at the Australian War Memorial in a special ceremony featuring the World Peace Flame and the release of a single dove.

“In my view they had sacrificed their lives for the sake of their country in the same way as those blokes who went over the top at Pozières,” Dawson said.

To mark the 70th anniversary of Australian involvement in international peacekeeping efforts, the Memorial will also feature a display of photographs in the entrance corridor, honouring Australians who have served in peacekeeping and security operations across the globe over the last 70 years, and who continue in this role today.

For Dawson, who is now Head of Collection Services at the Memorial, the role of peacekeeper is an important one.

“Soldiers more than anyone get the fact that war is a pretty unpleasant experience, and that crockery gets broken in the process, so any attempt to achieve a solution through peaceful means is worth a go,” he said.

“Somalia felt hopeless, and I suppose you deal with that by trying to do the bit you are responsible for as well as you can, and not being overwhelmed by the hopelessness of it, and by trying to help the people you are responsible for.”

Dawson was awarded the Conspicuous Service Cross for service in Somalia in 1995, and was deployed to the Solomon Islands in late 2002 as the commander of the Australian service contingent in its role with the International Peace Monitoring Team (IPMT).

“The Solomon islanders had been conducting something that looked a lot like a civil war,” Dawson said.

“It’s quite easy to get caught up in asking why are we here, and saying it’s all broken and it’s hopeless, and there’s no way out of it. But the role of the commander is to encourage and inspire, and to get people to focus on the job they need to be doing, rather than worrying about the grand strategic picture.

“One of the most encouraging things in the Solomons though was that at the end of January the schools automatically started. It wasn’t because the government had done anything. It was because mothers of the Solomon Islands had arranged teachers, and cleaned out the school houses, and got the pencils and the chalk and sent their kids off to school. And that was encouraging.

“There was a kind of grass-roots feeling of we can do this, which we didn’t really get a sense of in Somalia. You do look for green shoots and encouraging signs and you get a sense of whether things are sliding off, or getting worse, or are just broken, or whether there are signs of hope for the future.”

Dawson went on to become Australia’s first Military Representative to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation and the European Union and was deputy commander of the Australian Joint Task Force in Iraq. He retired from the Australian Regular Army in 2013 with the rank of Major General after 40 years’ service, but will never forget his time peacekeeping in Somalia and the Solomon Islands.

“It’s hard to tell as an outsider, but I didn’t get a sense that the Solomon Islands were as traumatised as some parts of Somalia,” he said. “Thousands of people had been killed in Somalia, and there were hundreds of young men who had gone off the rails and seen some appalling things in the Solomon Islands, but they were probably recoverable. In my view, there were people in Somalia, who had been brought up with violence, who had killed and watched their friends being killed, who were going to be very difficult to save.”

Brian Dawson: "Any attempt to achieve a solution through peaceful means is worth a go."