'It was the hairiest thing in the world'

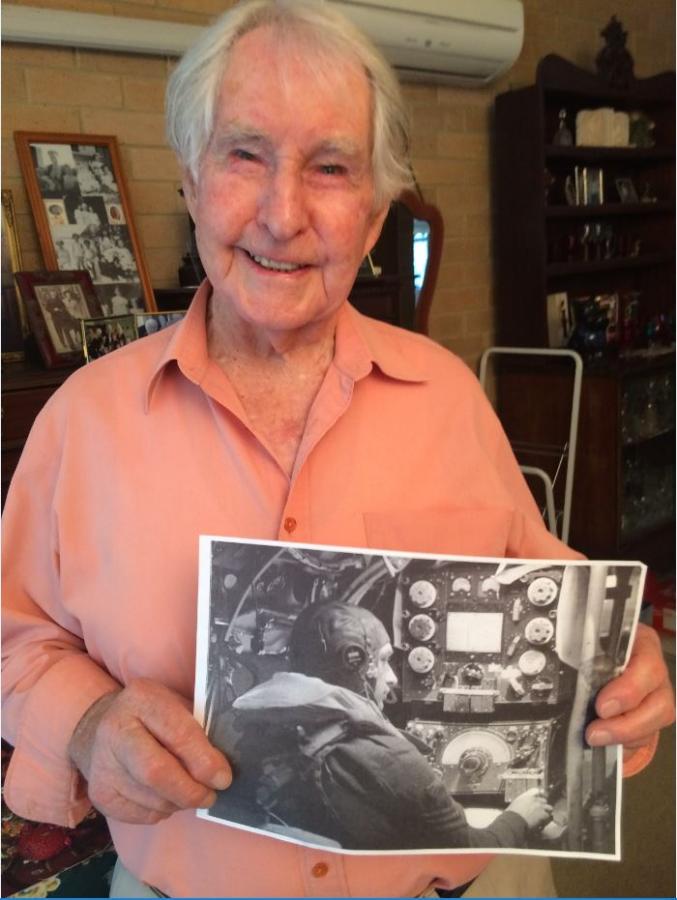

Portrait of Bruce Robertson.

Bruce Robertson was a wireless operator during the Second World War when he heard something through his headset that didn’t make sense.

“I was on a watch at two o’clock in the morning, and was turning a dial around on a receiver, listening in case an aeroplane came back in trouble, and this loud Morse code hit me in the ears,” Robertson said. “I couldn’t write it down. It didn’t make our letters. And so I thought, ‘It’s got to be Japanese.’ There was no other [explanation], so everyone came running, and sure enough it was Japanese.”

It was the night of 31 May 1942 and three Japanese midget submarines had entered Sydney Harbour. Robertson was on the midnight to dawn watch at Richmond and had heard “what they called Kana code” in the early hours of 1 June 1942.

“We didn’t have any radar, [but] we had two direction finding stations … and they honed in on the signal to find where it was coming from. We concluded it was a sub, and it was. It was right off Sydney Heads, and it was the mother sub for the midget submarines that had come into the harbour, and we think that perhaps it was waiting there to pick them up when they came out of the harbour, but, of course, they never came out of the harbour – they were destroyed.”

One of the midget submarines became entangled in the boom net across the harbour and was blown up by its occupants. A second entered the harbour and fired torpedoes at the cruiser USS Chicago. It missed the target, but one torpedo struck the barracks ship HMAS Kuttabul, killing 21 men. The submarine then disappeared, its fate a mystery until it was discovered by a group of amateur divers off Sydney's northern beaches in November 2006. A third midget submarine was destroyed by depth-charges before it could fire. The midget submarine on display in Anzac Hall at the Australian War Memorial is a composite of two of the submarines that entered the harbour that night, a night Robertson will never forget.

“There was a Lockheed Hudson bombed up on standby all the time to patrol on the coast – there were 37 ships sunk and destroyed by torpedoes just on our coast here – but this bomber couldn’t find them,” Robertson said. “It was a dark night, and they were probably submerged anyway … but that’s how things started, and the signal came through the air force in my headphones … The air force didn’t even realise this had happened until a couple of years ago, and they became very excited about it.”

Bruce Robertson: "This loud Morse code hit me in the ears." Photo: Courtesy DVA

David “Bruce” Robertson was born in Sydney in March 1920. It was a childhood meeting with aviator and First World War pilot Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith after his Trans-Pacific crossing that really sparked Robertson’s interest in flying. This interest, combined with his background working in a radio shop near Martin Place in Sydney, made him a perfect candidate to be a wireless operator in the Royal Australian Air Force when the Second World War broke out, and after serving in the militia for three years he joined the RAAF. When asked why he decided to enlist, he smiles.

“I don’t think anyone can truthfully answer that,” he said simply. “It’s just you felt that you had to. You didn’t know why, or what, or anything else about that, but all the young fellows were joining up, and you just joined up … I was in bed on a Sunday night, and I heard Prime Minister Menzies speaking over the radio. He finished saying, ‘Australia is now at war with Germany,’ and my mother came in and said, ‘Don’t think you’re going to the war.’ But, of course, I did.”

After training at Sydney and Point Cook in Victoria to become a wireless operator, learning Morse code, theory, and physics, he joined 30 Squadron in March 1942. Deployed to New Guinea, where the squadron’s Beaufighters provided aerial support to Australian and Allied troops, Robertson remembers arriving at Milne Bay, “the wettest place on earth, bar none.”

“It never stops raining,” he said. “It’s so wet, that they can’t have an airstrip – well, they couldn’t then, so they joined 30-foot long strips of steel together and coupled them like a Meccano set and made an airstrip. It was like hills, and valleys, and sideways, and all sorts. It was a terrible thing to take off and land on, and on one occasion, one of our aircraft just slipped of the strip and destroyed a Lockheed Hudson as well.”

Robertson is talking over lunch ahead of a visit to the Australian War Memorial to remember his mates and pay his respects. It’s a far cry from his days at Milne Bay when he lived on a diet of bully beef, dehydrated potatoes, and powdered milk and eggs, and had to shake the weevils out of the bread. “I’m alright,” he says with a laugh as he takes a break from eating to share his story. “I’ve been without bully beef for a while.”

Bruce Robertson: "My mother ... said, ‘Don’t think you’re going to the war.’ But, of course, I did.”

He remembers New Guinea as being incredibly hot, with no buildings, and the men sleeping six to a tent with the aircraft parked just outside.

“We had four Beaufighter aircraft there to keep the Japanese warships quiet,” he said. “They were shelling and the Beaufighters flew … so that they were level with the ships, and would strike them with four cannons and six machines guns…

“The Kittyhawks were wonderful too. They were only a mile away, and they would take off and fly into the coconut palms. The Lever brothers had a coconut plantation there and as far as you were concerned there were coconuts in any direction. The Japanese were up in the palms, sniping at the Australians, and the Kittyhawks went through and shot them out of the trees. It was just low level and they wore their guns out – they went back, reloaded, and the guns wore out – and that’s what they did, and they were marvellous.”

Robertson was also with the squadron when it supported operations during the Kokoda campaign. “Our aircraft were wonderful,” he said. “They destroyed the Japanese supply lines, and one of our pilots told us that an army intelligence officer ... said [they] found all this Japanese tinned food riddled with Beaufighter bullets.”

Robertson still wonders how the men who fought along the Kokoda trail managed. “It was the hairiest thing in the world to get there, let alone, get into the Kokoda track,” he said. “There was a road cut out of the mountainside, and the roads to the track … wouldn’t have been two feet from the edge of a sheer drop … I looked down the side of the track, and there, a thousand feet down, were trucks lying down there. They’d gone over the edge. They didn’t even get up there. It was so hairy. I don’t know how they managed it all. And they took 25-pounder guns up there.”

Robertson will never forget the relief he felt when the war was finally over. “It was just wonderful,” he said. “I was just recently married, and it was fantastic. We knew the day before that something was happening, we just didn’t know what, so I jumped on a troop train to Sydney … and the next day it was over.

“There was great excitement, and the people next door said, ‘Come in, we’ve got to celebrate.’ We went in and we had a glass of sherry, and in those days people didn’t drink like they do today … so to come home from next door after a sherry we had to hold onto the fence. That’s how ridiculous it was. And then we went into the city, and it was great. It was a wonderful time.

“I tell everybody, ‘Don’t go to war. Don’t go to war.’ It’s no picnic, and … when somebody tells me they were too young, I say, ‘I’m so pleased you were.’”

Bruce Robertson: "I tell everybody, ‘Don’t go to war. Don’t go to war.’ It’s no picnic." Photo: Courtesy DVA