Caterpillars, goldfish and guinea pigs: badges of the (un)lucky clubs of the Second World War

Whether walking back to safety from behind enemy lines, parachuting out of a disabled aircraft, crashing into water and being saved by a life raft, or enduring horrible burns from a plane crash, the stories of near misses experienced by aircrew during the Second World War are remarkable. As a symbol of the camaraderie between the men who had experienced these near misses, numerous clubs were formed, each with a distinct badge or patch to represent the wearer’s exploits. The following are a few examples of the badges crafted for some of these clubs, and some stories of men ‘lucky’ enough to earn themselves membership.

Late Arrivals Club

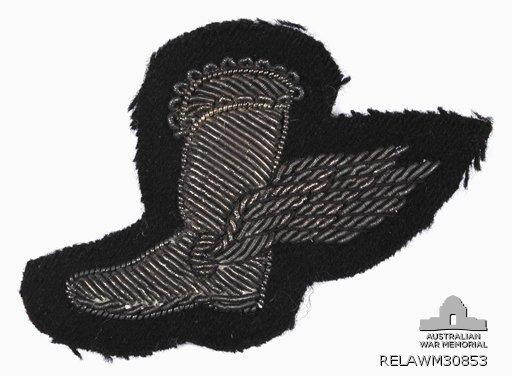

The Late Arrivals Club or Winged Boot Club honoured those who walked back from behind enemy lines. Members were awarded certificates with the words, “It is never too late to come back,” along with a patch or badge that could be worn on the left breast of flying suits. An extract from The Libyan Log by E. G. Ogilvie (an account of the Empire Air Forces in the Western Desert, July 1941-July 1942) states that the Late Arrivals Club was formed in the summer of 1941 in the desert but other accounts suggest it originated with staff members of Hobson and sons (London) Ltd., a firm of civil and military tailors.

Late Arrivals Club embroidered patch

Late Arrivals Club silver badge

The Caterpillar Club

The Caterpillar Club, which was first formed in 1922 shortly after Lieutenant Harold Harris made an emergency jump at McCook Field near Dayton, Ohio, offered membership to tens of thousands during the war who used parachutes made from caterpillar-produced silk to bail out of disabled planes. The Irvin Air Chute Company awarded unofficial badges in the form of gold caterpillars with red eyes along with membership certificates.

Caterpillar Club Badge : Flight Sergeant N Macdonald, 156 Squadron RAF

This Caterpillar Club badge is associated with the service of Flight Sergeant Norman Macdonald. Macdonald was born in Glasgow, Scotland before immigrating to Australia in 1937. He enlisted in the RAAF in Sydney on 11 October 1941 and qualified as an observer in March 1942. He embarked for Canada on 25 May as part of the Empire Air Training Scheme where he qualified as a navigator and was promoted to sergeant in October.

Embarking for the United Kingdom on 27 October Macdonald disembarked in Bournemouth on 5 November. Attached to 460 Squadron RAAF as a flight sergeant on 29 June 1943, Macdonald flew 17 operations as a navigator before transferring to 156 Squadron RAF. He joined the crew of Lancaster JB472 as navigator and flew his first mission on 23 November - a night raid on Berlin. This was closely followed by another night mission to Berlin on 26 November.

On 2 December JB472 took off from Warboys airfield for their third raid on Berlin. In a report given by Macdonald after the war he describes what happened to their aircraft as they flew over eastern Germany:

'Attack by enemy fighter reported by rear gunner - pilot acknowledged, took evasive action and just then we were hit. Crew put on chutes aircraft in steep dive. At approx between 17 and 15, 000 feet violent explosion. I was sucked out the starboard side of aircraft. Regained consciousness at approx 4,000 feet opened 'chute landed ok. I believe pilot jettisoned bombs endeavouring to save crew and aircraft but aircraft crashed 20 miles north of Hannover. The next day I was captured in the goods yard of the village railway station by 2 German soldiers who were searching for me and taken to identify wreckage of aircraft from which German officials had removed the bodies of my 6 colleagues. Taken to Frankfurt for interrogation put into solitary confinement then to Stalag IVB.'

Stalag IVB prisoner of war camp was located near the town of Muhlberg, just off the Elbe river. Macdonald was interned from 18 December 1943 until he was liberated on 23 April 1945. Macdonald returned to Australia and was formally discharged on demobilisation on 2 March 1946.

Other 'Parachutist Clubs'

GQ Parachutists Club badge

This badge is presented to those who qualify for membership of the GQ Parachutists Club by making an emergency descent from aircraft and using GQ Parachute Company Ltd equipment. The centre of the badge depicts a man making a parachute descent whilst the badge is completed on either side of the parachute by a pair of wings. The front of the badge bears the letters GQ while on the reverse side appears the inscription "saved my life". Each badge presented wasnumbered in sequence, and on the left-hand reverse side was engraved the name of the person to whom it was presented. On the righthand side is engraved the date of his descent.

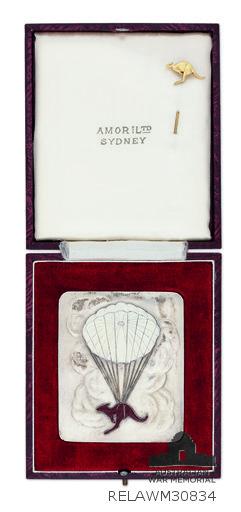

Roo Club badge and plaque

The gold kangaroo pin badge of the Roo Club was presented to those whose lives had been saved by the use of a Dominion-made parachute. The silver plaque, depicting a kangaroo making a parachute descent, was inscribed on the reverse side: "Presented by Light Aircraft Pty. Ltd. To [space for name] on qualifying for membership in the Roo Club having made a compulsory bale-out on [space for date] using a Dominion parachute".

The Goldfish Club

The Goldfish Club (following from the success of the Caterpillar Club) honoured airmen who were rescued after crashing/landing in the sea and taking to their dinghies. The Club wrote that

Money, position or power cannot gain a man or woman entry to the exclusive circles of the Goldfish Club. To become a member, one has to float about upon the sea for a considerable period with nothing but a Carley Rubber Float between one and a watery death.

The club was founded by the P B Cow and Company of Farnborough, manufacturers of rubber aircraft survival dinghies, and was supported by other makers of aircrew rescue dinghies. Each 'wavy line' was meant to represent the number of times an airman relied on a dinghy for survival. Originally it was intended to produce a metal badge, but the metal could not be secured, and due to wartime fabric rationing restrictions, the patches were embroidered on material taken from old dinner suits donated by staff from P B Cow and Co Ltd.

Goldfish Club cloth patch : Pilot Officer A G G Richmond, 230 Squadron, RAF

This patch relates to the service of Arthur Gerald Graham Richmond, of Brisbane, Queensland. A jackeroo and storeman and packer of New Farm, Brisbane, he had completed 12 hours of flying training at Archerfield, Brisbane prior to enlisting with the RAAF on 26 April 1940 at Brisbane. Richmond received initial training in Australia before embarking for overseas service from Sydney on 3 February 1941. He arrived in the Middle East on 24 March and was attached as a navigator to 230 (Sunderland) Squadron, RAF, based at Aboukir Bay near Alexandria, Egypt, where he spent 5 months. He then trained in South Africa (where he met his future wife, Violet) before returning to 230 Squadron on 14 July 1942.

It relates to an event for which Richmond was awarded the George Medal on 7 September 1942. Sunderland W3987, with a crew of eleven flying to Alexandria for an engine change, crashed on take-off at Aboukir Bay, killing 8 members of the crew. The port outer engine had required changing due to a major oil leak, but after a test flight, was considered stable enough to fly to Alexandria. Richmond had control of the aircraft at take-off and stated that ‘on reaching about 75 feet swing developed to port and smoke began to fill the cockpit.’ At this point the commanding pilot, 29 year old 400226 Flight Lieutenant Alan Frederick Howell, RAAF, took over the controls, by which time Richmond recalled that ‘it was practically impossible to see anything in the cockpit’ and the plane began to lose height. Witnesses stated the Sunderland ‘hit water at high speed, bounced high into the air and hit water again with port wing first’. An eight foot swell decided their fate, with no recovery possible, and the Sunderland crashed. Although severely lacerated, Richmond saved his wireless air gunner who was trapped in a pool of burning oil with a broken leg, then supervised the rescue of three more crew members. After recovering at 64 General Hospital, Richmond returned to operations with 230 Squadron (undertaking anti-submarine and escort patrols in the Mediterranean) until he was transferred to 461 Squadron, RAAF, at Pembroke Dock, Wales, in October 1943. On 28 February 1944 Richmond was promoted to Flight Lieutenant. The majority of his work with 461 Squadron consisted of anti-submarine patrols in the Bay of Biscay and convoy patrols. Richmond was the first member of 461 Squadron to fly on D-Day, and he spent June and July 1945 escorting surrendered U-Boats to England. He was discharged on 21 February 1946.

The Guinea Pig Club

Guinea Pig Club badge

The Guinea Pig Club was started by aircrew who had been horribly burned and disfigured in the Battle of Britain and were treated by innovative surgeon Sir Archibald McIndoe at Queen Victoria's Hospital in East Grinstead, West Sussex. Immobilized for weeks and recovering for months, the men in McIndoe’s ward started a drinking club - helped by the free beer given them during their recovery. The men decided to call themselves 'The Guinea Pig Club' as they were all, in some way, test subjects of new techniques. Between the club’s establishment in July 1941 and its disbanding in 1945, it welcomed 649 members. Of those, at least 19 were Australians.

Ken Gilkes, an Australian pilot in the RAAF, was just 20 years old when he was shot down as he piloted his Stirling Bomber back to his East Anglia base after a sortie over Europe in 1943. He landed the plane in a ball of flame and was seriously burnt on his face and hands. Not all of the crew survived. Gilkes was one of the lucky ones because he was transported to Queen Victoria Hospital, where he came under the care of McIndoe, who was pioneering new techniques in the treatment of burns victims and experimenting in the art of plastic reconstructive surgery. McIndoe had noticed that burn victims who crashed into the ocean recovered more quickly than those who did not, so he began using saline baths in the grafting process which replaced tannic acid as the grafting solution of choice.

Over the next two years, Gilkes was slowly given a new forehead, eyebrows, eyelids, cheeks and chin as skin was removed from his buttocks and thighs and, layer by layer, attached to build up his face. His hands were also slowly repaired, and he used to joke that he could get away with murder as he no longer had fingerprints. In 1946, Gilkes returned home to Australia and married his childhood sweetheart, Roma Bessell-Browne, who had waited faithfully for him. She said, "You haven't changed. You might look a bit different, but you are the same person." An enthusiastic sailor, Gilkes was warned to stay away from bright sunlight and the salt water since his new skin was rather sensitive. He ignored the doctor’s orders only to find that the mixture of sun and spray further sped up his healing process.

The Guinea Pig Club held reunions over decades to celebrate their incredible recoveries and honor the man who made it possible. The last was held in East Grinstead in 2007, which Gilkes attended. The last surviving Australian Guinea Pig, Gilkes died in November 2014 at the age of 91.