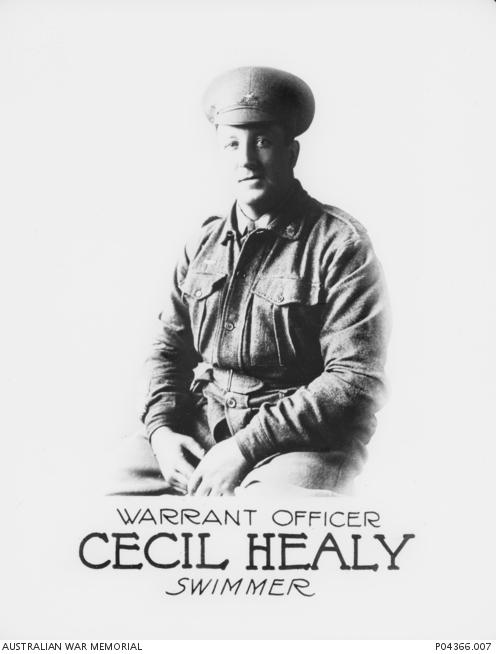

Remembering Cecil Healy

Cecil Healy’s actions at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics have been described as one of the most selfless acts of sportsmanship in Olympic history.

But it was his actions on the Western Front just a few years later that would see him remembered at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra on the 101st anniversary of the Armistice that ended the First World War.

Delivering the commemorative address at his first Remembrance Day as Governor General, David Hurley paid tribute to Healy, the Australian swimming champion and Olympic gold medalist whose life was cut short by war.

Governor General David Hurley paid tribute to Cecil Healy in his commemorative address.

“Cecil Healy had no love of the military, no desire to fight, but he recognised that his values and his freedom were threatened,” General Hurley said.

“In September 1915, Cecil, despite his reservations about the causes and justification for the war, enlisted in the AIF.

“Given his age – 33 – and his commercial experience, he initially served behind the front line as a Company Quarter Master Sergeant. He was always organising activities to help troops survive the effects of homesickness, the stresses of the battlefield and the drudgery of waiting for the next action or ‘stunt’.

“In May 1918, he could no longer accept that he was not bearing his share of the risks on the battlefield and undertook officer training to become an infantry platoon commander, a position with one of the shortest life expectancies in the First World War.”

Three months later, on 29 August 1918, Cecil Healy was shot and killed leading his platoon during the Australian attack on Péronne.

His friend, Major Sydney Middleton, an Australian Olympic gold medal oarsman and captain of the Australian rugby team before the war, wrote to Healy’s father and brother.

“By Cecil’s death the world loses one of its greatest champions, one of its best men,” he wrote. “Today, in the four years I have been at the front, I wept for the first time.”

Healy had achieved Olympic glory just six years earlier, winning gold in the 4x200 m swimming relay at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, and silver in the Men’s 100 m event – after what has been described as one of the greatest acts of sportsmanship in Olympic History.

When the US team, including race favourite Duke Kahanamoku, was disqualified from the event after failing to turn up for the semi-finals because of confusion about the race start time, Healy refused to swim without Duke.

Healy successfully protested until the Olympic Committee relented and the American swimmer and his countrymen were permitted to compete. Kahanamoku went on to win the gold medal, later declaring that Healy was “the true Olympic champion”.

When the First World War broke out just a few years later, Healy answered the call. He was one of more than 414,000 Australians who enlisted during the war and one of 62,000 who never made it home.

“Reluctantly he chose to serve, fully understanding the risks contained in that decision,” General Hurley said. “In that, he is an example to us today. In that, we should be forever grateful to the thousands of men and women like Cecil who we remember today. Lest we forget.”