"In years to come, I can say I was the first man of the 37th Battalion to enter the front line”

Charles Herbert Johns was a prolific diarist. Within the space of 16 months, he had filled four notebooks with his experiences and observations of life and service in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF).

A 24-year-old inspector under the Vermin Destruction Act, Johns enlisted in the AIF at Wangaratta, Victoria, on 13 January 1916. He was posted to the newly raised 37th Battalion, which was formed in Seymour from recruits drawn from Melbourne, north-east Victoria and the Gippsland region. Johns was made a private in the battalion’s D Company under Captain William Symons VC, a veteran of the Gallipoli campaign who had been awarded the Victoria Cross for his distinguished leadership at Lone Pine in August 1915.

The 37th Battalion spent four months training around Seymour, before the unit embarked from Melbourne on 3 June 1916 for service overseas. It was on the morning of his embarkation, as the battalion prepared to move from Seymour Camp, that Johns penned the first entry in his diary: “2am Reveille. Exultant commotion on all sides mingled with the calls of the ‘early bird’ (Mr Rooster).” The men marched three miles through the rain to board a train for Melbourne. “As we near the city”, Johns wrote, “there is a continual wave of flags, handkerchiefs, towels – in fact anything that is handy to the ladies at the moment … to convey their good wishes.”

Johns’ account of his ship’s arrival at Devonport and the “monster” whales along the coast.

Following a seven-week voyage, Johns’ ship docked in Devonport, England, on 25 July. “All is bustle”, Johns observed, “preparing for disembarkation”. The men had sighted dozens of whales along the coast as they made for port – “monsters some of them were”, Johns noted with some awe. His ship, flanked by destroyers “on all sides”, was then guided into the harbour by a torpedo boat. The men were taken ashore by ferry and almost immediately boarded a train for Salisbury Plain, where the 37th Battalion would spend the next four months undergoing additional and more specialised training. It was here that Johns’ leadership potential was first noticed. He was promoted to lance corporal on 19 September and appointed to a bomb throwing section.

The 37th Battalion finally embarked for France, and the Western Front, on 22 November 1916. Johns would be in the front lines within the week. The battalion was posted to Armentières, a relatively quiet area known as “the Nursery Sector”, used to familiarise new and inexperienced battalions with service at the front. On 29 November, Johns wrote: “at 11am ‘yours truly’ (who is leading the Bombers) finds himself in the front line. In years to come, I can say I was the first man of the 37th Battalion to enter the front line trenches.” With his battalion due to take over occupation of the trenches the next day, Johns and some 30 others had been sent forward and attached to a New Zealand battalion to gain an insight into the routine on the front line.

Johns took part in the watch from the bomb and fire-steps during the evening and, early the next morning, patrolled a gap in the trenches. Of the experience, he observed:

… one has to remain perfectly quiet & the cold is bitterly intense. Flare lights are going up the whole of the time & in addition old Fritz has ½ a dozen search lights on our front & these he keeps swinging about across no man’s land. While these lights are on a man he must remain perfectly still, no matter what his position might be for the slightest movement is readily spotted & it means a machine gun’s bullets about one’s ears.

At day’s end he added, “and their [sic] ended my first day & night in the front line trenches of this greatest of all wars.”

Over the bitter winter of 1916–17, the 37th Battalion took part in frequent patrols of no man’s land and raids on the German lines. Johns was promoted to corporal, and then sergeant, and in April his battalion was sent further north to fight in Belgium.

By 18 May 1917, the 37th Battalion was occupying a section of the front line near Ploegsteert, just north of the French border. That morning was uneventful, Johns noted: “A very quiet day & evidently old Fritz is suffering a recovery from last night.” He was soon to regret these words. Just before 9 pm, the battalion’s front was assaulted by an intense artillery barrage and a fierce attempt by the Germans to raid the Australian lines. Johns later wrote in his diary:

This is the most severe stunt I have been under & don’t know how I came out with a head on my shoulders … I nearly had my head taken off about a dozen times by whizz-bangs & was turned up & slightly wounded by a HE [high explosive] shell that landed in the trench at my feet.

Shrapnel from the shell left Johns with a cut above his right knee. Despite the wound, he remained on duty and continued to rally and organise his men to resist the German attack. Only afterwards, once the Germans had dispersed, did Johns have his wound attended to at an advanced dressing station.

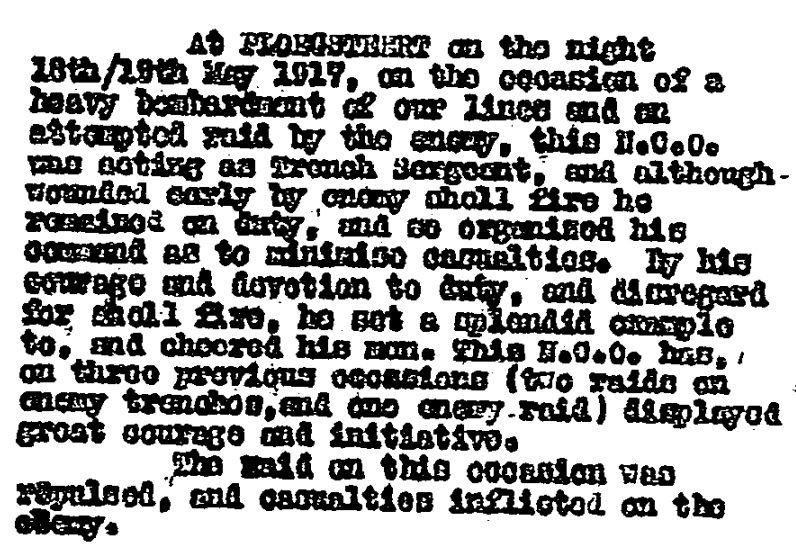

A week later, Johns was informed that he had been awarded the Military Medal for his “courage and devotion to duty” and for setting “a splendid example” at Ploegsteert. Johns was almost embarrassed by the attention: “I was staggered at the news for I had done nothing to deserve it.” Despite his modesty, the official citation for his award noted the “great courage and initiative” Johns had displayed on three previous raids.

The text of the recommendation for Johns’ Military Medal, AWM28 1/137

Over the following fortnight, the 37th Battalion prepared for its first major action on the Western Front: the Battle of Messines. The objective of the battle was to capture the ridge that ran from Ploegsteert Wood, through Messines to Mt Sorrel, deprive the Germans of the high ground and force them to reallocate their reserves, thereby relieving pressure on the French forces near Arras and Aisne.

The Battle of Messines began with the detonation of 19 mines dug beneath the German lines. It was an auspicious moment for Johns, who wrote: “Suddenly the whole place rocked as thousands of tons of earth was sent heavenward … & then [the men] were over the top and into it.” The first two objectives were secured in the morning and, just after 3 pm, the 37th Battalion prepared for the final phase of the advance. As Johns recounted: “We had 600 yards to go & after the first hundred we were entirely in the open & soon met with a withering machine gun fire”.

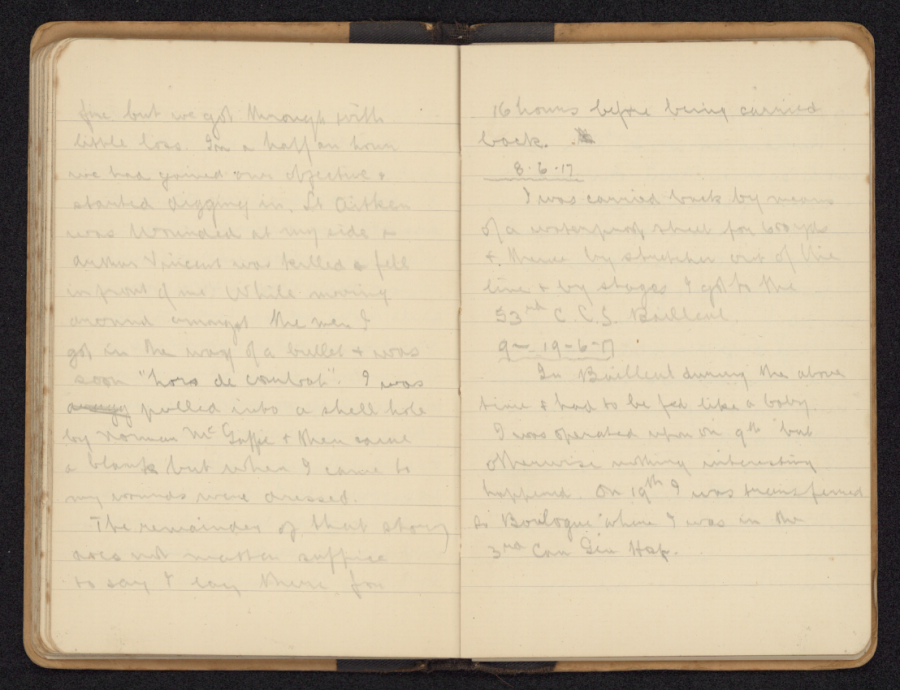

The men captured their objective within half an hour and had begun digging in when further machine-gun fire tore through the lines. Johns recounted: “Lt [Philip] Aiken was wounded at my side & [Sergeant] Arthur Vincent was killed & fell in front of me.” Johns began moving to reorganise his men when “I got in the way of a bullet & was soon ‘hors de combat’.” Shot in the chest, he was dragged into a shell hole and there remained, falling in and out of consciousness, for the next 16 hours until he could be evacuated to a casualty clearing station.

“While moving amongst the men I got in the way of a bullet…”

The wound ended Johns’ war. He spent the next four months under treatment and convalescing at hospitals in France and England, until he had sufficiently recovered to embark for home. He arrived in Melbourne on 18 November 1917 and, as the ship pulled up to the pier, Johns wrote that “the ship’s bugler played Home Sweet Home … & it was indeed Home Sweet Home.”

After Johns died in 1953, his diaries were lovingly cared for by his family for 60 years until donated to the Memorial in 2014. The diaries now form the Private Records collection PR05626.