'I know that I am fighting for a new world in which my people will get a better deal'

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, please be advised the following article contains names and images of deceased people.

When Charles Mene returned to Australia at the end of the Second World War, he realised that, for him, the war wasn’t really over.

He went to enjoy a beer with his mates in Brisbane; but he didn’t even get to sit down.

Refused entry, he was told, “We don’t serve black men here.”

Charles Mene had fought in the Middle East and New Guinea during the war, and would go on to be awarded the Military Medal for bravery in Korea.

He had enlisted in September 1939 to “fight for Country and family”, hoping that he and his family and friends could live and work in a post-war Australia, free from any restrictions imposed on them because of the colour of their skin.

“Like anyone, I thought I should fight for the country,” he said later. “I had brothers and sisters involved and I thought I should join too.”

He had explained his reasoning to the Tribune newspaper in June 1944 while serving with the 2/33rd Battalion and recovering from a bout of malaria.

“But now,” he said. “I know that I am fighting for a new world in which my people will get a better deal.

“I want to come back to an Australia where my people will have full rights as citizens, to an Australia where Aboriginal children will have the right to education, to work and to a healthy, happy life.”

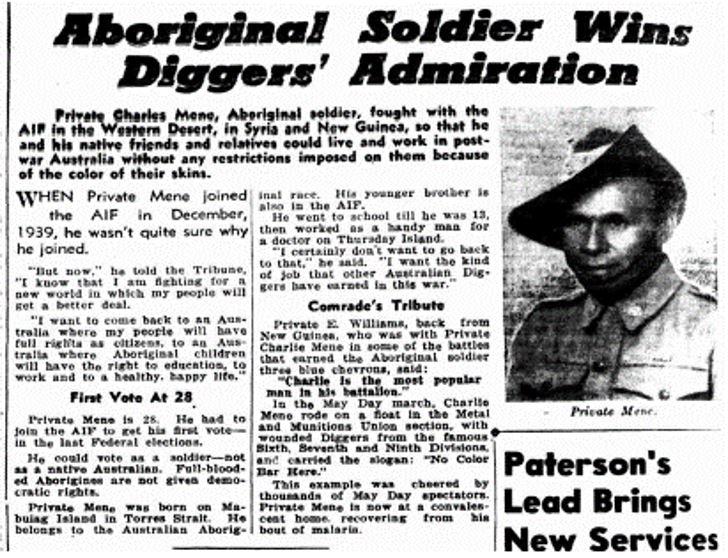

Charles Mene featured in the Tribune newspaper on 1 June 1944.

Regarded as “the most popular man in his battalion”, Charles Mene was born on Mabuiag Island in the Torres Strait on 21 January 1915.

His father was a pearl diver and the family survived on his father’s pearling pay, supplemented by produce from the family’s gardens and food caught from the sea.

Charles followed in his father’s footsteps and went to work in the pearling industry when he left school at the age of 13. He was working as a “house boy” for the Government Medical Officer on Thursday Island when the Second World War broke out.

He shared his story in an oral history interview with the Australian War Memorial in 1991 and featured in the exhibition Too Dark for the Light Horse.

“I left school [at Mabuiag Island],” Charles said. “I was only in Grade 4 … and then I went on the boats, trochus [shell] fishing for a while, and then I didn’t like the trochus fishing, so I finished up at the Island – working at Thursday Island – in the pearling station. Later on, I worked for Doctor Nimmo … looking after the house, cleaning and so on.”

He was 24 years old when he enlisted in the Militia on 3 September 1939: the same day Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced the beginning of Australia's involvement in the war.

“When the war break out, they form a garrison to guard the wireless station,” he said. ”Some of the boys I know, they enlisted, and I thought, ‘Well, I might as well be in it too.’”

Three brothers would also serve during the war.

Corporal Charles Mene, pictured third from left, on board SS Devonshire bound for Korea, c. 1952

Charles himself would go on to serve in three different conflicts over the next 20 years.

He transferred to the newly formed Second Australian Imperial Force in December 1939, and travelled to Brisbane for training. It was the first time he had travelled outside the Torres Strait.

“The day we leave Thursday Island, we were in the Army,” he said.

“Being new, it was a bit difficult at first, and then, when I got to know the boys and the training, I enjoyed it.

“This was my first time away from Thursday Island.

“Yes, it was a great change for me. It was difficult because, Islanders, you see, we got our own language.

“I had to mix with the boys and sometimes I found it a bit difficult to understand the English, but anyway, I learned my way.

“I had no difficulty making friends and getting on with the white soldiers.

“We were all in it [together].”

Sydney, NSW, c1941. The troopship Queen Mary as she enters Sydney Harbour to transport troops for overseas service.

Charles embarked for overseas service from Sydney on board the troopship Queen Mary, and arrived in Scotland as the last remnants of the British Expeditionary Force were being evacuated from Dunkirk.

He recalled seeing the German Luftwaffe while training on the Salisbury Plain in England.

“We could see the Battle of Britain, you know, the planes,” Charles said.

“That was the first time we saw the plane coming in and saw the [bombing] damage.

“One of the [German] planes flew right in over our camp in Tidworth Park.

“There was a Spitfire right behind him, and I believe he got him.”

Although Charles was a gunner with the 1st Anti-Tank Regiment, he was soon fighting in the rugged mountains of Syria as part of the 2/33rd Battalion. The Regiment had been split up to form infantry battalions, and Charles’ battery, the 4th, had become part of the 2/33rd Battalion, fighting in the Middle East.

“That was my first action in Syria,” Charles said.

“Before that I’d seen a lot of bombing, but Syria was the first action.

“I was in the [battalion’s] support platoon, in the Bren Gun Carriers.

“Well, I thought it was just training, until I saw dead soldiers.

“Then I woke up to myself.”

Tripoli, Syria, 1941: Members of the 2/33rd Battalion with a Bren gun on Thaoulin Island.

By early 1942, the 2/33rd was on the move again. The Australian government had been forced to turn its attention to the Pacific and the heightened threat in the region following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

Charles’s unit was sent to New Guinea to reinforce tired and battered troops in the gruelling fighting along the Kokoda Trail.

Between 13 September and 11 November 1942, Charles’s Battalion would lose more than 100 men, either killed or wounded, and experience some of the toughest fighting that Australian soldiers would endure during the war.

“I was still in the Bren Gun Carriers, but up there [we] were just footsloggers,” Charles said.

“We had our machine-guns … the Vickers Machine-gun, the Medium … we had them ready, but we never used them. We acted as a rifle company.

“Most of the time we were with the Battalion Headquarters, and I could hear … we were close to the action during that time, and I could see the wounded coming back. It was very, very hard … with the muddy [conditions] and malaria.”

New Guinea, 1943: A patrol of the 2/25th and the 2/33rd Battalions crossing the Brown River.

Charles’s unit went on to fight in the desperate battles at Gona, Ramu Valley, and Shaggy Ridge, before taking part in the Borneo landings at Balikpapan.

“The only time we used the Vickers machine-gun was when we got to Gona,” Charles said.

“They called on us to bring the machine-guns up, but when we get up to the position our Commanding Officer want us to fire from, we found that we couldn’t see the target. The kunai grass was so high, you know, and you can’t see the target, so we had to go back again.”

“After [the advance on Lae] we went back again, up the Ramu Valley, right up to Shaggy Ridge.

“The Japs were just up on the high ground and you were on the low ground looking up at him, only 20 or 30 yards away …

“Most of the time these 25-pounder artillery shells were going over your head and sometimes they hit the trees above you.

“Shaggy Ridge was very, very steep and by the time you got up there it was very hard going.

“I found it hard going down too. The old legs [were] a bit wobbly from the effort.”

Shaggy Ridge, New Guinea, 1944: Australians crossing a new log bridge between Guy's Post and Shaggy Ridge.

Charles was in Borneo when the war ended, and volunteered to serve in Japan as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF).

“I had to go up before the Commanding Officer,” he said.

“And when I went up he had a look at my pay book and said, ‘You have no red marks in your pay book … I’ll recommend you and I’ll give you some friendly advice … You’ll be in Australian uniform up there, and there’s different countries be looking upon you. Don’t forget you’re the ambassador for Australia and your behaviour must be good.’

“I still remember that.

“I like to see Japan, because … [we’d] been fighting them, and I thought I’d better go up and see what the place was like.”

Charles would go on to serve during the Korean War and the Malayan Emergency.

“I was getting out [of the Army] in 1950, and when I got here in Brisbane, waiting around in the depot, the Korean trouble started,” he said. “So I changed my mind.”

An experienced combat soldier, Charles served in a machine-gun platoon, while occasionally leading less-experienced rifle companies in battle.

He later recalled how he and his men had to use explosives so they could dig trenches during the bitterly cold winters. The ground was frozen, which made digging impossible.

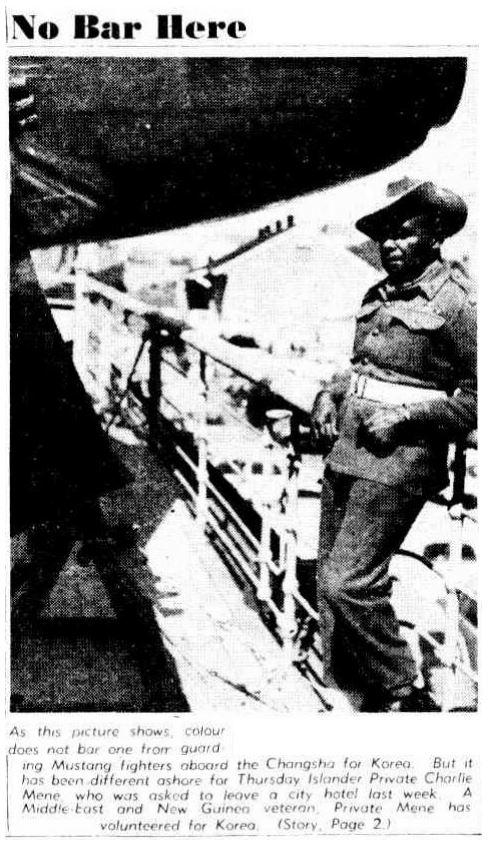

Charles Mene was featured in the Brisbane Telegraph on 28 August 1950.

When Charles’s section came under heavy artillery and mortar fire in July 1952, he carried the wounded back to safety.

“It was a daylight raid at Hill 227,” C said.

“My section was on the right, like, of Hill 227, and later on, there was a patrol, a snatch patrol, and that [was] when I run into a bit of trouble.

“My platoon commander was down below from me, with his runner, at the river.

“I was on the high ground, and that’s when I got attacked from the rear.

“Well, I was very close to them then, and I did fire on them, because this man, this Chinese, he got my man on the right flank.

“He was coming toward me, and I had to do something about it. I had the Owen gun and I put the whole magazine onto him to make sure he’s gone, and then, after that we withdraw, and I got the men out.

“One was wounded … walking wounded, and one had to be carried.

““Our mortars and artillery then start firing and we withdrew ... under fire.

“That was at night … early hours in the morning, but we know where the track was to get back, but it was up the hill and down the hill.

“It was very, very awkward carrying the wounded…

“[But] I got them out all right.”

Charles was awarded the Military Medal for his actions that day.

But it would be another five years before he was formally presented with the medal.

Corporal Charles Mene receiving the Military Medal from the British High Commissioner to the Federation of Malay States, Sir Douglas MacGillivray.

Charles went on to serve during the Malayan Emergency, where Australians fought with British Commonwealth Forces against communist guerrillas hidden deep in the Malayan jungle. He was in Malaya when he was presented with the Military Medal by Sir Douglas MacGillivray, the British High Commissioner to the Federation of Malay States. The medal had been following Charles, always one step behind, from Korea to Japan, then to Australia and finally to Malaya.

After two years in Malaya, and 22 years’ of service in three different conflicts, Charles returned to Australia in 1961 and discharged from the army.

Reflecting on his service in 1991, he said the army had changed his life, giving him opportunities that he might never have had.

“Well, for me, with no special training or education,” he said.

“When I joined the army I only know what I had to do. My skin was on the line.

“I was quite happy, and I learned a lot while in the army. I learnt by seeing what you do … training and all that …

“I managed to see a lot of the world while I was in the army, so I suppose that’s something that mightn’t have happened if I hadn’t joined the army.”

Charles settled in Brisbane with his wife, Michi, whom he met while on leave in Japan, and their daughter, Patricia. He died in 1999.

Michael Bell is the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the Memorial. A proud Ngunnawal/Gomeroi man, he is working to identify and research the extent of the contribution and service of people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who have served, who are currently serving, or who have any military experience and/or have contributed to the war effort. He is interested in further details of the military history of all of these people and their families. He can be contacted via Michael.Bell@awm.gov.au