'Aviation is still new, but it has set some of us thinking, and thinking hard'

Clifford Peel as a lieutenant in the Australian Flying Corps. Photo: Courtesy Doug Peel

On 20 November 1917, John Clifford Peel wrote a letter that would become the inspiration for the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

The 23-year-old from country Victoria was a young lieutenant in the Australian Flying Corps when he first wrote to the Reverend Dr John Flynn, who ran the famed Inland Mission across outback Australia, on 2 November.

“Cliff” Peel had been studying medicine at Melbourne University when he enlisted during the First World War and was an avid reader of Flynn’s work, The Inlander, which told of “Life on Australia’s Frontiers”.

Peel was training to become a pilot and had started thinking about how Flynn could use aeroplanes to transport his mission and help people in remote areas.

“I have taken unto myself wings like the bird, or at least entered the new world of aviation,” Peel wrote to Flynn. “I am becoming more and more convinced that the air is to provide many solutions to that exceedingly vexed aspect of inland life [transportation] … I would be only too glad to dot down a few of the wanderings of my mind on paper and send them to you.”

Cliff Peel's photograph of the Bristol Scout - "the bus" - he learnt to fly in. Photo: Courtesy Doug Peel

When Flynn wrote back expressing his interest, Peel composed a more detailed letter outlining his vision as he embarked for overseas service on the troopship Nestor.

Sadly, Peel never got to see his idea come to fruition. Less than a year later, and just weeks before the end of the war, he disappeared while undertaking photographic reconnaissance over the Western Front in France.

He was just 24 years old and never knew that his dream of using aircraft to help save lives would become the blueprint for the creation of the Royal Flying Doctor Service in 1928.

The Chief Executive Officer of the Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia, Martin Laverty, said Peel was a remarkable man whose vision had helped transform the way healthcare is provided in the outback.

“Whilst the use of aircraft is taken for granted today … flying was just in its infancy when Cliff Peel was already applying its potential to the greater good of people who lived in remote Australia,” Laverty said.

“Whilst he was going through his own training and preparing to serve the country during the First World War, he was thinking about how to serve inland Australia using the relatively new knowledge that he would have gained about flying … and that idea eventually became the Flying Doctors.”

Cliff Peel in the Bluebird, which he called the "mechanical cow", in 1917. Photo: Courtesy Doug Peel

In his letter to Flynn, Peel wrote of the “marvellous possibilities” provided by the new technology.

“Aviation is still new, but it has set some of us thinking, and thinking hard,” Peel wrote. “Perhaps others want to be thinking too. Hence these few notes…"

In his now famous letter, he not only examined the difficulties of using aviation, but presented a full cost-benefit analysis outlining safety issues and listing forecasted flying times between the main locations.

“That [letter] is the business case that started the Royal Flying Doctor Service, and … it’s part of the origins of the Flying Doctor that we both respect and are grateful for today,” Laverty said.

“It was literally an unsolicited letter from one person to another – [they] had never met [and] didn’t know each other – but Peel sets out a business case as to why aviation would help Flynn in his mission work, and his business case, even by today’s standards, was really ahead of its time …

“He was one of the founders of what today is taken for granted – of using aviation to provide health care to those who live in remote Australia – and that same objective is unchanged 100 years later...

“Imagine if Peel’s letter had not been sent.”

Clifford Peel at Laverton in 1917. “In the not-very distant future," he wrote. "I can see a missionary doctor administering to the needs of men and women scattered between Wyndham and Cloncurry, Darwin and Hergott. If the nation can do so much in the days of war, surely it will do its ‘bit’ in the coming days of peace – and here is its chance…” Photo: Courtesy Doug Peel

To commemorate the centenary of Peel’s death, members of his family and the Royal Flying Doctor Service travelled to the Australian War Memorial to attend a Last Post Ceremony and lay wreaths in his honour. Shortly after the ceremony, a Royal Flying Doctor Service PC12 aircraft performed a fly-over of the Memorial in recognition of his contribution to the service which was founded 90 years ago.

For Cliff Peel’s nephew, Doug, it was particularly special. He grew up hearing about his father’s oldest brother, and served in Vietnam.

“My old man was only 12 when Cliff was killed,” Doug said. “But the whole family has always talked about him … and is incredibly proud.

“He was a pretty forward thinker … and what he did was beyond belief really. When you think of the planes they had in 1917, it was only in 1909 that they first flew the English Channel, and there weren’t a lot of them around, but he had the idea, and Flynn took it up, and ran with it.”

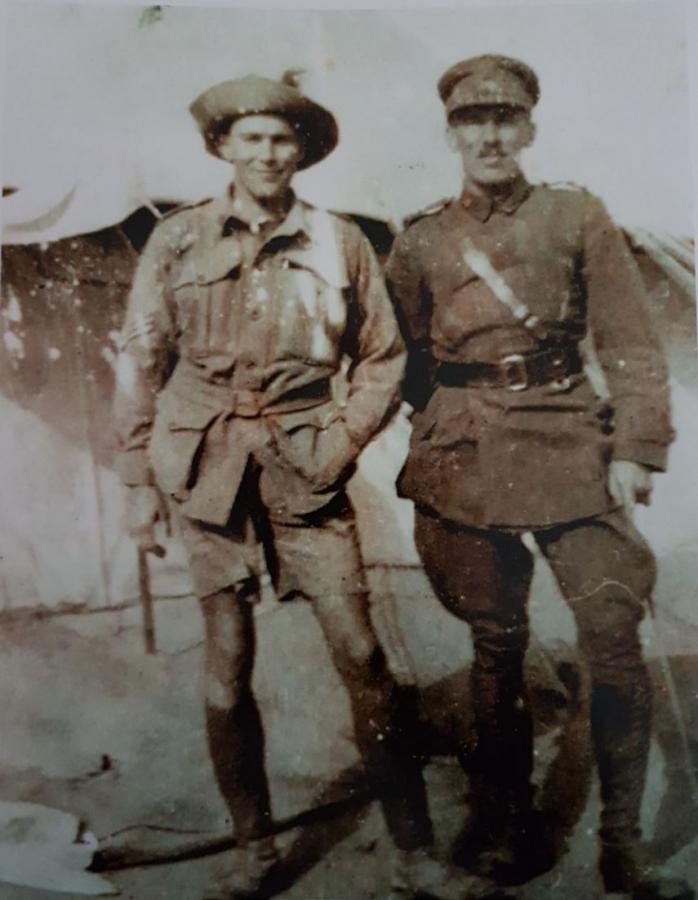

Cliff Peel, right, pictured with his brother George at the Suez. Photo: Courtesy Doug Peel

The eldest of nine children, Cliff Peel was born in April 1894 at “Tower Hill”, the family homestead built by his grandfather, George, in 1856, overlooking 75 acres of river flats by the Leigh and Barwon rivers at Inverleigh near Geelong.

“His younger brother George landed on Gallipoli as a stretcher bearer, and he was sending letters and things home all the time while Cliff was at university learning to be a doctor,” Doug said.

“I think to a degree that he thought he might have missed the war, so he volunteered when the Flying Corps had their second intake … and he was pretty busy learning to be a pilot.”

He trained in Maurice Farman Shorthorns, which he referred to affectionately as “The Bluebird” or “the Bus” in his letters home, and embarked for Europe in 1917, stopping over in Suez, where he met up with his younger brother George.

George had been Mentioned in Dispatches and awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions on Gallipoli and went on to serve in the desert battles of Romani, Gaza, and Beersheba before being invalided home with malaria.

A photograph of members of 3 Squadron with an RE8 in France in 1918. Photo: Courtesy Doug Peel

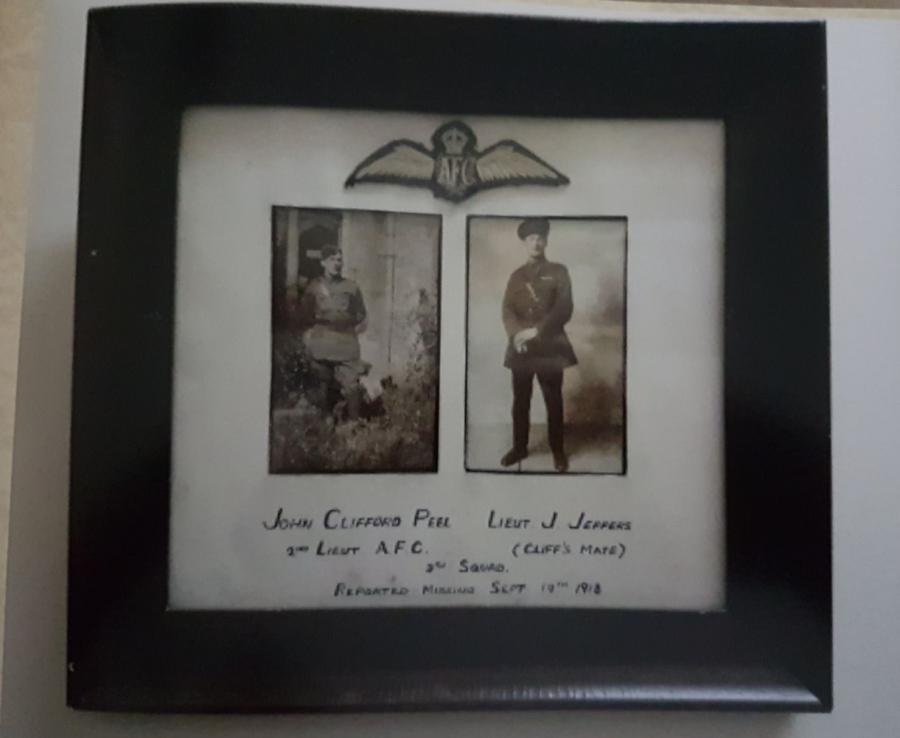

It would be the last time they ever saw each other. On 19 September 1918, Peel and his observer, Lieutenant J.P. Jeffers, were serving with 3 Squadron on the Western Front when they were ordered out on a reconnaissance patrol to photograph the line of the St Quentin Canal from south of Bellenglise to Bellicourt in northern France. When their RE8 aircraft failed to return, they were listed as missing in action.

A telegram notifying Cliff’s family reached Inverleigh just days before his brother George was due to wed.

“He was getting married and the postmaster got the telegram saying that Cliff was missing and they withheld the telegram until after the weekend because they didn’t want to spoil the wedding,” Doug said. “And that’s just how it was, I suppose.”

A photograph of Clifford Peel and his mate, John Patrick Jeffers, still hangs on the wall at Tower Hill. Photo: Courtesy Doug Peel

The family was left devastated by his loss, but it would be years before they would finally learn his fate. His RE8 had been attacked by German fighter near the village of Bellenglise and was shot down just seven weeks before the end of the war.

Today, Cliff Peel’s name is commemorated on the Arras Flying Services Memorial to the missing in France, and his photo still hangs on the wall at Tower Hill.

A century after his death, he is remembered as the man whose vision inspired the establishment of the Royal Flying Doctor Service, an Australian institution which has been providing medical care to outback communities for the past 90 years.

Clifford Peel's Memorial Plaque. Photo: Courtesy Doug Peel